-

Discovering the ecosystem of the tiger in Corbett

ANY mention of Corbett Park tends to be about its tigers and Jim Corbett, the colonial ...

Read More

-

Satyarthi co-traveller with every rescued child

EVEN today, across India, children from impoverished families are subjected to unspeakable horrors. Because of ...

Read More

-

Life lessons: How to succeed with failure

SOME months ago, this magazine published a tally of young students who had taken their ...

Read More

-

Freedom as it came and how it is remembered

WHEN Independence Day arrives each year, how should the spirit of the freedom struggle be ...

Read More

-

Beating the bookstore curse

AT a time when bookstores are rapidly closing across India, Kunzum is a rarity. It ...

Read More

-

A bird listing in Sanawar

LAWRENCE SCHOOL Sanawar, described by its headmaster, Himmat S. Dhillon, as “arguably the oldest co-educational ...

Read More

-

Hyderabad's chronicler has rare stories to tell

IT was Hyderabad’s famed biryani that first seduced Serish Nanisetti when he came to the ...

Read More

-

A reporter abroad: How to unpack a country for readers

INDIA’s globalization efforts will always be incomplete without a deeper understanding of other societies and ...

Read More

-

The deep forest and its many treasures in Arunachal

IT was the search for plants that hornbills feed on which brought Navendu Page, a ...

Read More

-

From the Hindutva beat, real Modi and Ayodhya stories

WHEN Nilanjan Mukhopadhyay began reporting on the RSS-BJP-VHP combine in the 1980s, it was not ...

Read More

-

The iconic garden

EVERYONE knows Lal Bagh but much remained to be told about it. It's all here ...

Read More

-

Tracking monks and pilgrims

THERE was a time when monks and wanderers travelled seamlessly from India to a swathe ...

Read More

-

Pre-loved books, anyone? Here is some shelf help

IF you happen to enjoy reading and are also a compulsive buyer of books, no ...

Read More

-

Social business: a prof offers theory, insights

SOCIAL enterprises have been proliferating in India as a result of the benefits of growth ...

Read More

-

Not just another air pollution story

THERE was a time when concern over air pollution used to be treated as an ...

Read More

-

What did you do in the lockdown?

The lockdown forced people to retreat into their homes and lead a different life, a ...

Read More

-

Eureka is in a new home happily with CMYK

In the midst of the pandemic, a small business which had closed down sprang back to ...

Read More

-

Deep dive: Inside story of wildlife reserves

INDIA’s wondrous natural heritage is still a hidden gem for most Indians. Not for them ...

Read More

-

Poverty and the elderly in India

Across the world, the coronavirus pandemic has drawn attention to the elderly. India has a ...

Read More

-

Uncivil Delhi: Cars, cows and rickshaws

How far has green activism by Delhi’s middle class benefited the city? It hasn’t resolved a ...

Read More

-

Ups and downs of India's bumpy democracy

While there seems broad agreement about Brazil, the Philippines, and Turkey being erstwhile democracies moving ...

Read More

-

The 'halla bol' world of Safdar Hashmi

Safdar Hashmi was all of 34 years old when he died. He was performing a ...

Read More

-

Teachers as heroes and rural schooling

An unusual yatra from March 2017 to November 2018 gave S. Giridhar the material for ...

Read More

-

Insider's account of India's nuclear setup

A decade ago this book would have hit the headlines. It is a testimony to ...

Read More

-

Mapping Delhi's water heritage

Vikramjit Singh Rooprai’s disarmingly modest pocket book is truly a contribution to the cause of ...

Read More

-

Workplace harassment

We know that women have the right to a safe workplace under the law. But ...

Read More

-

No limits to poll-time messaging

When India Votes is about the use of media by political parties when they campaign ...

Read More

-

Small and big stories of women's rights

Kalpana Sharma, the author of The Silence and the Storm, is admired for her insightful ...

Read More

-

Kerala's fishermen: Heroes of a terrible flood

Disasters make headlines and are remembered because of the disruption they cause. Life just can’t ...

Read More

-

Stories from a dissenting India

Battling for India, A Citizen’s Reader, edited by writers Githa Hariharan and Salim Yusufji, is ...

Read More

-

"There are different shades of the mind"

The editors of Side Effects of Living, Jhilmil Breckenridge and Namarita Kathait, met at a ...

Read More

-

Partition in the mind

The medical discipline of psychiatry in India is going through a phase of introspection and ...

Read More

-

An Adivasi's search for love

In 2017, Hansda Sowvendra Shekhar found himself at the centre of a storm when his ...

Read More

-

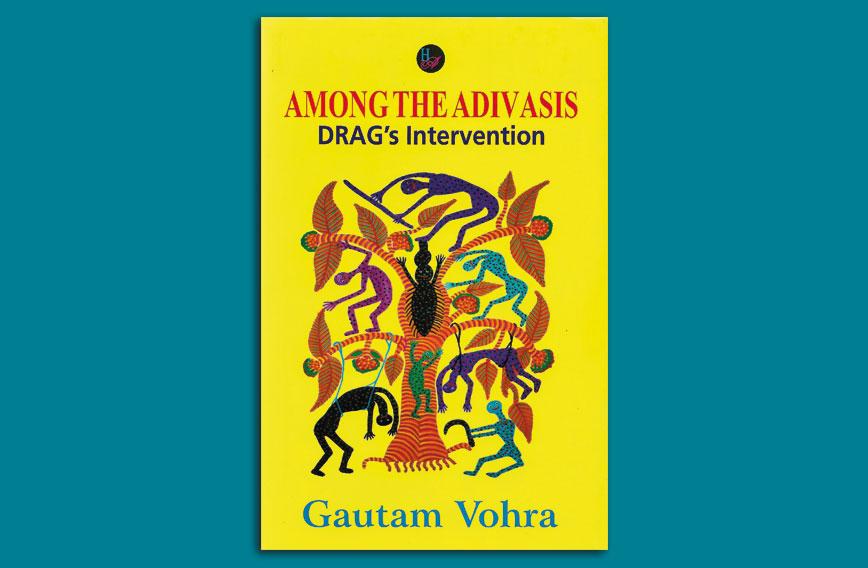

Gautam Vohra on DRAG, the NGO he and many others created to get tribals their benefits

The 1980s were probably the NGO sector’s most idealistic phase. Young, middle-class people, often ...

Read More

-

Yashica Dutt grew up a Dalit and spent her youth hiding her identity

In Coming out as Dalit, Yashica Dutt skilfully weaves her life story of growing up ...

Read More

-

Sudipta Sen takes us down the Ganga on many rare journeys

The Ganga strangely represents the physical manifestation of an accepted mythological duality — to be ...

Read More

-

Girl from a ghetto: Dreams, ambitions of Muslim women

he archetypal perception about Muslim women is that they are victims of Islam and of ...

Read More

-

On Campus: Essays on the problems in education

Education at the Crossroads is about a range of issues that bedevil higher education and ...

Read More

-

Timeless ideologies: Why Bhagat Singh is immortal

Everyone knows that Bhagat Singh was one of the most celebrated martyrs of India’s freedom ...

Read More

-

Fighting for tigers: Their rise and fall in Panna

Project Tiger, launched in 1973, had many successes and some failures, says Raghu Chundawat in ...

Read More

-

Barefoot historian says good bye to Kolkata’s streets

The village yogi never gets alms. Thus goes the oft-repeated Bengali saying. In other words, ...

Read More

-

In Nagaland, a wet paddy field has infinite value ?

In her remarkable book, The Flavours of Nationalism, Nandita Haksar recalls the important role food ...

Read More

-

Jugaad’s great, but comes with limitations

Jugaad has come to stand for a distinctive Indian way of finding solutions driven by ...

Read More

-

Partnerships and big ideas where they really matter

The Path Ahead is a collection of essays penned by people who are experts in ...

Read More

-

MFI to small bank: Ujjivan's amazing story

The story of Ujjivan, one of the largest Microfinance Institutions (MFIs) and its transformation into ...

Read More

-

Finding P.T. Nair among his old books in Kolkata

At a time when every armchair heritage activist cries “blue murder” whenever an alleged ancient ...

Read More

-

What battered Indians say

Harsh Mander’s collection of stories is by no means a reader’s delight. Nor are they ...

Read More

-

Bengali cooking decoded

If you have not been to the two Bengals (east and west), one in India ...

Read More

-

Tracing India's art cinema

The importance of this book, authored by V.K. Cherian, a film society activist and communications ...

Read More

-

Matters of the mind

At the recent release in Delhi of a book featuring writings by various psychotherapists, somebody ...

Read More

-

The bitter marriage

Malika Amar Shaikh was the daughter of the Marathi Communist trade union leader and folk ...

Read More

-

Story of a Dalit woman

Kautik on Embers is about life in a village in Umravati district of Vidarbha, infamous ...

Read More

-

Female street politics

Who would imagine that Bala, a leader of the Shiv Sena women’s ...

Read More

-

The pull of a past life, other reality

In the 21st century the world is often divided between believers and non-believers of one ...

Read More

-

The lost young migrants from the northeast

Nandita Haksar’s recent book, The Exodus is Not Over: Migrations from the Ruptured Homelands of ...

Read More

-

‘Decline in working women is worrisome’

In recent years, news about the declining number of women in the workforce in India ...

Read More

-

Young Indian urban women and their search for careers

In a time of skewed sex ratios, violence against women and girls and continued old ...

Read More

-

‘Empathy is important for meaningful medical care’

Dr Fazlur Rahman’s inspirational new memoir, The Temple Road: A Doctor’s Journey, begins with his ...

Read More

-

How PV’s middle way sought to strike a balance

A few years before P.V. Narasimha Rao passed away a former official of the finance ...

Read More

-

A better life at Swift Wash

Beautiful Women — Journeys from despair to dignity,' is a first-person narrative of 10 women ...

Read More

-

‘Migration not fully understood as yet’

MIgration is leading to mingling of identities across India. People migrate mostly for survival, jobs, ...

Read More

-

‘SEZs need enabling environment to succeed’

Ten years after the SEZ (Special Economic Zones) Act was passed, India has over 500 ...

Read More

-

The perils of research into societies in conflict

This is undoubtedly a brilliant book that will be discussed for a long time. It ...

Read More

-

‘Bant remains a Dalit icon whose voice rings true’

When Bant Singh’s daughter was brutally raped in 2000, he was just another Mazhabi Sikh ...

Read More

-

Being queer isn’t an illness

For most members of the queer community, their interface with the medical community is distressful. ...

Read More

-

The Bangladesh story

Professor Rehman Sobhan says he has sung four national anthems during his lifetime: God Save ...

Read More

-

Reporting from hotspots

Shyam Bhatia is back for a week at his mother’s house in New Delhi. It ...

Read More

-

Searching for Shiva in Pakistan

In the face of rising extremism and intolerance Haroon Khalid, journalist and educationist, sets off ...

Read More

-