Fighting for tigers: Their rise and fall in Panna

Usha Rai

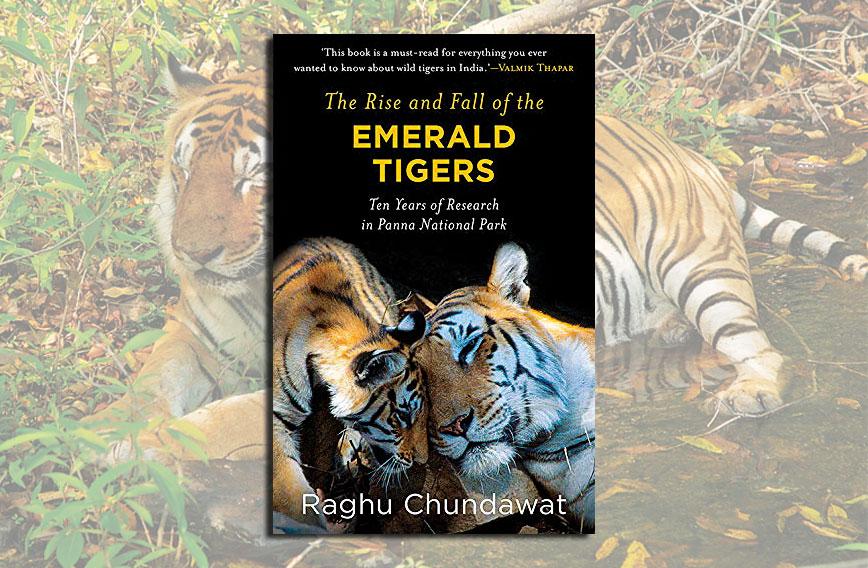

Project Tiger, launched in 1973, had many successes and some failures, says Raghu Chundawat in his latest book, The Rise and Fall of the Emerald Tigers. And one could not agree more. Based on 10 years of research, from 1996 to 2006, in central India’s Panna Tiger Reserve by radio collaring seven tigers, five females and two males, he weaves an intimate and fascinating account of the Panna tigers.

A total of 41 tigers (nine females, five males and 27 cubs) were identified and studied by Chundawat and his team in addition to five cubs monitored until they were adults. In fact, it seems as though the team’s endless forays into the jungle and their watch over the tigers and their prey kept poachers at bay.

The extensive support provided by P.K. Chowdhury, director of Panna Tiger Reserve, ended when a new management took charge. Facilities given, like tracking the tigers on elephants, were withdrawn and research inside the park was stopped. There was a spurt in poaching and tigers dispersing outside the protected area could not be monitored. Tiger mortality increased. A tigress found dead with two cattle carcasses was probably poisoned.

When Panna’s tiger population was on the decline no one would believe it. Then, in 2008, their extinction made headlines — sending shock waves. This was the second tiger reserve, after Sariska, where the animal had died out.

Had we not learnt any lessons from Sariska? Alerts on the swift dwindling of tigers were re-sent. Fortunately, the pressure built up by wildlife champions led to a change of guard at Panna and the reintroduction of tigers, three females, in 2009 followed by four more later. The tiger population bounced back but the recovery was not scientifically documented, says Chundawat.

It is time for a critical review, for new approaches that incorporate more inclusive conservation models, says the author, a renowned conservation biologist. In the coming decades the success of India’s conservation will depend on how well tigers thrive outside protected areas. The loss of distribution range signals extinction. Today, tigers survive in just seven percent of their former range. Threats to Panna continue. Interlinking of the Ken and Betwa rivers and the building of a dam on the Ken will shrink the Panna Tiger Reserve, and push out wildlife. Other protected areas face similar threats.

Chundawat pleads for a bigger landscape and scientific, long-term research to support harmonious growth of the tiger population. There was relief, and some elation, when the 2014 census showed 2,226 tigers. But this is less than the 2,500 tigers India had in the early 1970s when Project Tiger was launched. Though tiger numbers stayed intact for almost half a century, should they not have doubled? Numbers have been fluctuating. In 2008, the tiger population was down to a dismal 1,411 and the 2011 census showed 1,706 tigers. The status of tigers is worrying in most reserves, barring Corbett, Nagarhole-Bandipur and the central Indian highlands around Kanha, says Chundawat.

The noted scientist’s angst is understandable, but it is the innumerable stories of the Panna tigers that make interesting reading. Baavan or 52 in Hindi, so named because her eyebrow markings resembled the numerals five and two, is the tigress that the team radio-collared three times over nine years from 1997. She occupied the best habitat in Chapner and Bhadar, contributed 20 tigers to Panna through her cubs and their progeny, and also to the team’s understanding of tiger ecology. Her first three female cubs, born in April 1996, were also radio-collared as was the dominant male, Madla, who fought and drove out another male. By end-1999, the researchers knew there were four adult females and two males in Panna, making the tiger density three to four per 100 km.

By the end of 2001 there was evidence of seven resident tigresses, including three new ones. By early 2002 the tiger population in the area reached its peak — 28 tigers in about 400 km. In 2003-04, a significant number of tigers were lost to poaching. In 2006, a female tigress and her first litter were poisoned. The crash of the tiger population was faster than its recovery.

Resident tigresses had a reproductive span of 11 years, from ages three to 14. The short gestation period of around 100 days makes it a resilient species which is why Chundawat laments, “We have failed tigers by not providing for basic ecological needs and a secure environment in many protected areas.”

Tigers are largely peaceful and infanticide happens only when a male takes over a territory. If there are cubs from the previous male, destroying them encourages the female to come into oestrus and mating follows. If a male can settle down for four to five years he can sire more offspring from multiple females than a female can produce in her normal reproductive life of eight to 10 years.

In Panna, tigers were found mating throughout the year, the tigresses mating with more than one male during the oestrus cycle. Repeated and prolonged copulation is needed for conceiving.

Tigresses are extremely protective of their cubs. They don’t even go hunting until they are eight to 10 days old. Chundawat recounts the story of a sloth bear chased away after it stumbled on a cave that had three-week-old cubs. That same night the mother moved the cubs to another location nearby.

Cubs become confident of their surroundings when they are five or six months old. Teaching them to hunt could begin with a mother capturing a sambar fawn and leaving it alive for her cubs to play with. As they grow older, they are introduced to bigger prey. The research team saw a tigress catch and give a wild boar to her cubs who took hours to kill it while the mother watched from a distance. Another tigress was seen teaching six- and seven-month-old cubs to climb a tree. On a more serious note, the researchers also found the females’ survival rate in Panna was lower than that of the males.

This book is a must-read for all those truly interested in saving our tigers. The section on the need to revamp tiger conservation and how to handle the several small satellite populations near protected areas provides new insights.

Comments

Currently there are no Comments. Be first to write a comment!