Freedom as it came and how it is remembered

WHEN Independence Day arrives each year, how should the spirit of the freedom struggle be remembered? There are speeches, flag-hoisting ceremonies and parades aplenty. But how does one rise above the noise and, in a rapidly changing world, remain connected to the values and commitment of a generation that put an end to colonial rule and, through diverse efforts, fashioned a modern Constitution and republic?

For present-day Indians to cherish and protect the liberties they now have and move strongly ahead, it is important for them not just to symbolically acknowledge independence, but to also be imbued with the sacrifices and struggles, the hopes and aspirations that were invested in a democracy that was expected to hold its own in the world.

A museum here or there or history textbooks caught up in cyclical controversies don’t serve this end. Remembering the past should be a much bigger project that involves everyone in an unfettered search. It should bring events and people alive and ensure they remain memorable. It is in such stories that the efforts and experiences which finally shaped and became the foundation of a progressive nation will be found.

Seen thus, Independence becomes more meaningful and a daily celebration of what everyone stands for. It is more inclusive as well — whether looking back on the past or recognizing what ordinary folks now strive for. It goes from mere ceremony to being work in progress, which is the better way of keeping future generations engaged.

Researchers and journalists have an important role to play. They have the skills to go far and wide and deep at the same time. Good journalists know how to engage with their subjects and their audiences.

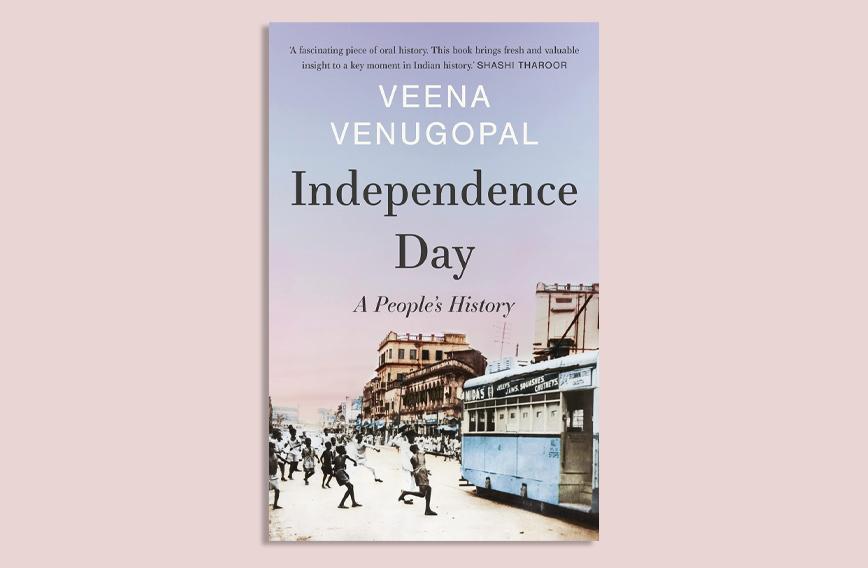

Veena Venugopal has shown what is possible with her outstanding book, Independence Day: A People’s History. She has identified and interviewed people across India who saw August 15, 1947. They narrate to her their personal stories — each unique because the stories are primarily about themselves. But the narration is also set on the larger canvas of what happened on that day in the country and particularly where they were.

Veena Venugopal has shown what is possible with her outstanding book, Independence Day: A People’s History. She has identified and interviewed people across India who saw August 15, 1947. They narrate to her their personal stories — each unique because the stories are primarily about themselves. But the narration is also set on the larger canvas of what happened on that day in the country and particularly where they were.

The stories reveal the way the leaders of the freedom struggle were revered, the vastness of the country and yet its binding unity, the respect the media enjoyed and the important role it played in informing people, the challenges of being employed in government but having siblings and children fighting British rule, the heartbreak of a communal divide and the resulting waves of brutal violence.

Venugopal has used oral history deftly to give us a page-turner. The accounts flow smoothly, but are also intricate with many layers. They are not too long and not too short. Clearly, she has had to work with her subjects, helping them piece together their recollections and fill in the gaps. Selecting her subjects was important. They couldn’t be too young at the time of Independence or so old now that they wouldn’t be lucid. Discovering them was obviously not easy, but she has mostly made good choices.

The book’s strength is that the narrators are mostly unknown. The usual movers and shakers on Independence would have been complete bores. So, here are people who have something to say which you are not likely to have heard before. It also means that you can begin by reading any one of the 15 stories. There are surprises aplenty.

The first story is of Tarun Kumar Roy who was in Krishnagar. Born in 1929, he was 18 years old at the time of Independence. Krishnagar is currently in the Nadia district of West Bengal. But when Partition was taking place, it was not clear whether Krishnagar would be in East Pakistan or India.

Roy and his family were among a large number of Hindu families in the Hindu-majority Krishnagar who waited anxiously to know where the dividing line would fall. There was confusion till the end. Cyril Radcliffe’s report was with Mountbatten and a decision was awaited. But on August 15 it seemed that Krishnagar would be in East Pakistan and the Pakistan flag was hoisted. Days later at midnight on August 18, it came to be known that Krishnagar was, in fact, in West Bengal. The next day the Indian flag was hoisted.

So it was that Independence Day was celebrated twice in Krishnagar. On August 15, when Krishnagar was thought to be in Pakistan, the local Congress leader hoisted the Pakistan flag and Hindus like Roy made sure they were present at the ceremony. Everyone shouted, "Pakistan Zindabad."

When it came to the hoisting of the Indian flag on August 19 it was done by the Muslim League MLA and the Muslim district magistrate Naseeruddin, handed over charge to a Hindu magistrate and left for Kushtia which was in East Pakistan. Everyone said, "Jai Hind."

When it came to the hoisting of the Indian flag on August 19 it was done by the Muslim League MLA and the Muslim district magistrate Naseeruddin, handed over charge to a Hindu magistrate and left for Kushtia which was in East Pakistan. Everyone said, "Jai Hind."

Those were stressful times. Roy remembers the communal rivalries and tensions. Partition and the run-up to it divided people in more ways than geography. Rumours abounded and old associations became strained or fell apart. Independence was, of course, welcome and was better than being under the British, but in Krishnagar Hindus braced themselves for being free in a Muslim-dominated East Pakistan. Partition didn’t make anyone happy.

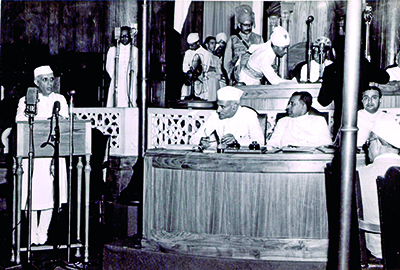

The stories are in parts brilliant in the way they take the reader to 1947. Here is a paragraph from Roy’s account: “At midnight I stood in front of a radio shop. There was a huge crowd. We stood there, all of us, and heard Nehru speak the now famous words —our tryst with destiny — and that is how I knew power had changed hands, and we were citizens of the new nation of East Pakistan. Nobody felt happy about this. In the crowd there were a significant number of Muslims and they didn’t look happy either.”

The stories reveal a lot about the social milieu. The status of women, for instance, in Ambika Menon’s story. Her father was a municipal school headmaster who went from Ooty to Dehradun. The family home was in Palakkad in Kerala where she felt the pulse of the freedom movement in discussions within the family. She ended up being the only girl studying at Doon School because her father was a teacher there. She wanted to study medicine and be a doctor, but her grandmother didn’t allow her. She went on to teach in schools, but there was no real independence. Finally, there was marriage and after 32 years divorce — after which she began discovering a life she could call her own.

The stories tend to meander as is only to be expected. They aren’t just focused on Independence Day. But they succeed in recreating the setting and mood. They move between the very personal and the larger canvas of the freedom struggle and impending independence.

An interesting paragraph in Menon’s story reads: “The freedom struggle was a strong presence in my childhood. In Kerala, the vernacular press — Mathrubhumi and Manorama — play a huge part in the state’s readership.... There were long and passionate arguments about all the topics of the day. Often there were critiques of the movement. You couldn’t help but hear these. All the great heroes — Gandhi, Nehru, Patel — were household names for my brother and me. It must have been the same for other kids during that time.”

Children of today don’t have the benefit of such exposure. They can’t because families are smaller and the generation that knew about the freedom struggle has passed. These are also cynical, colder and less idealistic times. Bringing back that old spirit is important for India, but the question is how. Oral histories like these are a form of storytelling that works, but much more needs to be done for future generations to feel more rooted.

Comments

Currently there are no Comments. Be first to write a comment!