SANJAYA BARU

Over the next several weeks the festival of democracy will keep Indians busy and entertained. The jingle on my radio issued by the Election Commission says, “Watan dabayega button”! It’s a call to arms. With the singular exception of Indira Gandhi’s Emergency era (1975-77) general elections to the Lok Sabha have been held on time since 1952 and Indians have ensured a smooth transition from one elected government to another.

Much can be said in praise of the election process and improvements made to the organisation of elections. Several officials involved in conducting elections have written important books that testify to the magnitude of the Indian achievement. If there is still one complaint that one can legitimately have, it is to do with the duration of the Lok Sabha elections. This year it will be conducted over a period of six weeks and through seven phases, beginning on April 11 and ending on May 19, with results being declared on May 23. The Indian electoral process is the world’s most long-drawn one.

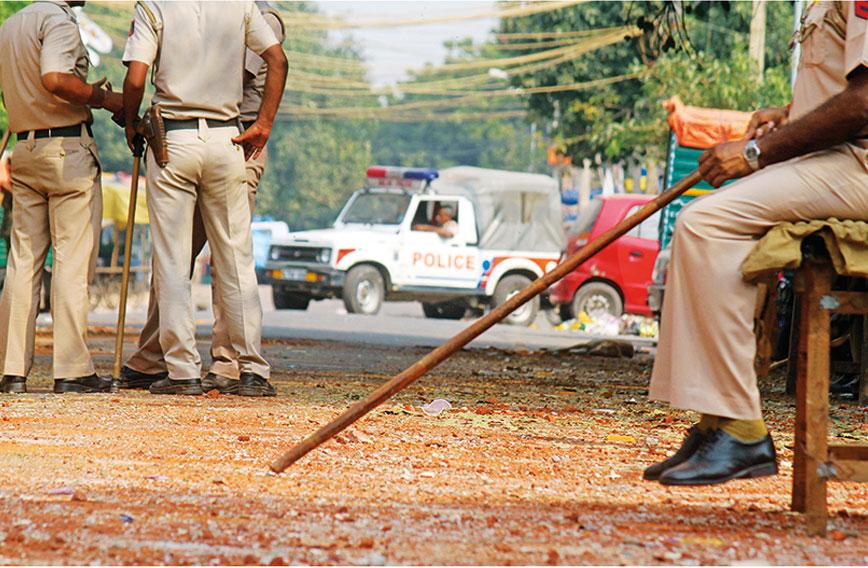

What accounts for this inordinately long duration? The Chief Election Commissioner was asked this question at the press conference on March 10. His reply was astounding and revealing. There is a shortage of security personnel, said the CEC, because all political parties have always demanded that the security of both candidates and election booths has to be provided only by the central police forces and not by the state police.

The limited number of central police forces have to be moved around the country by train, given time to acclimatise to the local conditions before they can be deployed, and so on and so forth. The CEC explained that the only reason the electorate in Bihar, Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal would vote over seven phases while Andhra Pradesh and Telangana would vote on just one day has to do with logistics pertaining to the movement of the central forces. This does sound odd. In any case, in no state do political parties have any faith and trust in the impartiality and efficiency of the state police. State police are, it would seem, viewed as partisan instruments in the hands of the ruling party of the day.

This is an astounding revelation, coming as it does from a responsible government functionary like the Chief Election Commissioner! It testifies to the complete politicisation of the state-level law and order machinery. If state police cannot be trusted to be impartial in providing security to all during the elections, what kind of a police force do we have?

The CEC’s reply would not come as a surprise to anyone familiar with the deterioration in the leadership and quality of personnel of state police and their politicisation across the country. In a shocking revelation made three decades ago by the then director of the Central Bureau of Investigation to a committee on “The activities of crime syndicates/mafia organisations which had developed links with and were being protected by government functionaries and political personalities”, chaired by then Union Home Secretary N.N. Vohra, it was stated: “All over India crime syndicates have become a law unto themselves. Even in the smaller towns and rural areas, muscle-men have become the order of the day. Hired assassins have become a part of these organisations. The nexus between the criminal gangs, police, bureaucracy and politicians has come out clearly in various parts of the country. The existing criminal justice system, which was essentially designed to deal with the individual offences / crimes, is unable to deal with the activities of the mafia; the provisions of law in regard to economic offences are weak ….”

The report went on to note, “Like the Director, CBI, the DIB (Director, Intelligence Bureau) has also stated that there has been a rapid spread and growth of criminal gangs, armed senas, drug mafias, smuggling gangs, drug peddlers and economic lobbies in the country which have, over the years, developed an extensive network of contacts with the bureaucrats /government functionaries at the local levels, politicians, mediapersons and strategically located individuals in the non-State sector. Some of these syndicates also have international linkages, including the foreign intelligence agencies.”

Since 1993 the rot may well have gone deeper. Even at that time Vohra noted in his report, “In the course of the discussions, I perceived that some of the members appeared to have some hesitation in openly expressing their views and also seemed unconvinced that government actually intended to pursue such matters.”

Ever since this report was submitted, Indians have been familiar with the phrase “the nexus between politicians, criminals and police”. Thanks to successive Election Commissions, we now know the names of all criminals contesting elections and the criminal records of elected politicians. What many citizens may not know is the intimate link between politicians in power and the local police. It is this nexus that politicians themselves worry about at the time of elections. Hence the demand that local police be kept away from guarding election booths. There has been any number of instances over the years when local police have been involved in organising what has been dubbed “booth-capturing” by one or the other candidate.

Apart from the cost of transporting central forces and providing other related logistics support, there is the additional cost of a prolonged election campaign and ensuring safety of ballot boxes over an extended period of time. This is further complicated by the fact that election campaign restrictions prevent the government in office from functioning like one until elections are completed. The lockdown on policymaking can also be debilitating.

The era of booth-capturing and ballot box stuffing has mercifully come to an end with the introduction of electronic voting machines and the provisioning of adequate central security forces. Going forward, the Election Commission and all political parties should try and see how the duration of elections can be reduced, at least to a month if not a fortnight.

Sanjaya Baru is a writer based in New Delhi

Comments

Currently there are no Comments. Be first to write a comment!