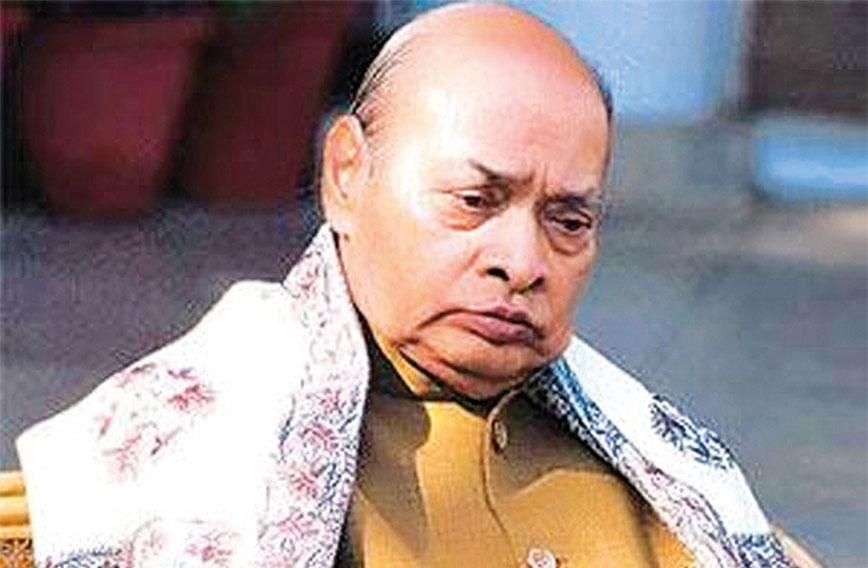

SANJAYA BARU

THE birth centenary of former Prime Minister P.V. Narasimha Rao will be observed on June 28, 2021. The government of Narasimha Rao’s home state of Telangana has demanded that he be conferred the nation’s highest honour, Bharat Ratna, posthumously. It remains to be seen if Prime Minister Narendra Modi or President Ram Nath Kovind, whose prerogative it is to select a nominee for the Bharat Ratna, will now do the former prime minister that honour.

Given the fact that a Congress party-led government, that was in office for an entire decade after Narasimha Rao’s death in December 2004, chose not to so honour one of their own, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) can well argue that there is no need for it to do so now. The case for Narasimha Rao being conferred the Bharat Ratna is very strong. Apart from the trivial argument that if former Tamil Nadu Chief Minister M.G. Ramachandran and Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi could be conferred that honour then why not Rao, the stronger argument is based on Rao’s legacy.

As I have summarized in my book, 1991: How Narasimha Rao Made History (Rupa, 2016), India owes it to Rao for not only pulling the economy out of its worst-ever post-Independence crisis with the initiatives that he, and his finance minister, Manmohan Singh, took in 1991 but for also giving a new direction to India’s foreign policy in the context of the end of the Cold War and the collapse of India’s most powerful post-War ally, the Soviet Union.

It is no exaggeration to suggest that Prime Minister Narasimha Rao laid the foundation of what may be termed ‘post-Nehruvian’ economic and foreign policy. What is more, no successor in that high office has, over the past three decades, reversed any of his historic initiatives in both realms of policy.

Narasimha Rao’s biographer, Vinay Sitapati, has also claimed in his authoritative account of the former PM’s life, The Half Lion (2016), that it was Rao who had made all the necessary preparations for India’s nuclear tests of 1998 and the credit for India’s status as a nuclear weapons power should go to him. Taken together, these three achievements on the economic, foreign policy and national security fronts are adequate to qualify Narasimha Rao for a Bharat Ratna.

The only two arguments made against this claim are that, (a) Rao’s reputation was besmirched by allegations of corruption, with he being the only former PM to have had to appear in a court of law to defend his actions in public life and (b) that he was responsible for not preventing the demolition of the Babri Masjid in Ayodhya in December 1992.

The purely cynical reply to those objections would be that public figures with other sins have been honoured with a Bharat Ratna so why raise moral arguments only in Rao’s case. The more objective response would be to underline the fact that he was absolved of the allegations made against him in a court of law and that the 1992 decision of the central government not to interfere in the discharge of its duties by a duly elected state government, in Uttar Pradesh, was a unanimous decision of the entire Union cabinet and not just the PM. Both these arguments are factually valid, even if some insist that they are morally weak.

When historians look back at the last decade of the 20th century they will no doubt point to the destruction of the Babri Masjid as an important milestone in the unfortunate history of communal tension on the Indian subcontinent. However, it remains to be seen how they will compare this event with the communal violence that followed India’s partition and continued through the post-Independence period across the subcontinent, including the killing of Hindus and Muslims in dastardly incidents in Delhi, Mumbai, Gujarat and so on.

On the other hand, no historian is likely to challenge the now widely held view that Narasimha Rao’s tenure marked a turning point in India’s rise as a post-colonial economy and polity and that Rao’s policies laid the foundation for India’s subsequent rise. A rise that has been disrupted only recently during the tenure of Prime Minister Narendra Modi. Narasimha Rao launched a new phase in Indian history with policies that two of his important successors, Atal Bihari Vajpayee and Manmohan Singh, took forward during their tenures.

Political scientists may make a further point about Narasimha Rao’s legacy. During the long years of the prime ministerial tenures of Indira Gandhi and Rajiv Gandhi (1966-89) the Indian polity had become used to a centralized form of governance with political power residing increasingly within a small coterie based in what is these days popularly called “Lutyens’ Delhi”. Narasimha Rao practised a more consensual form of governance that also respected India’s federal institutions. Unlike Indira and Rajiv, Rao maintained good relations with opposition political leaders and state chief ministers of different political parties. He had excellent political and personal relations with an opposition leader like Vajpayee as he did with state chief ministers of non-Congress parties like Jyoti Basu and N. Chandrababu Naidu.

Rao’s style of consensual politics was continued by Vajpayee and Singh. Both led coalition governments and so were required to take partners along, but their style was also inclusive and consensual. Indian polity had become used to governance with a softer touch through this era, from 1991 to 2014. The return of a single-party government with an assertive leader who, like Indira Gandhi, has chosen to centralize all power within the office of the prime minister has, therefore, been jarring. Many even within the BJP yearn now for Vajpayee’s more easygoing and friendly style of leadership.

When the nation celebrates Rao’s centenary this June-end, many will recall his contribution to economic policy and, perhaps, foreign policy. However, it is useful to also recall his contribution to a new style of functioning of the Prime Minister’s Office. The imperious PMO of the Indira-Rajiv era gave way to the consensual leadership style of turn-of-century politics. At a time when once again there is widespread concern about centralization of power and authoritarian politics one must pay special tribute to Narasimha Rao’s civilizing legacy.

Sanjaya Baru is a writer and Distinguished Fellow at the Institute for Defence Studies & Analyses in New Delhi.

Comments

Currently there are no Comments. Be first to write a comment!