SANJAYA BARU

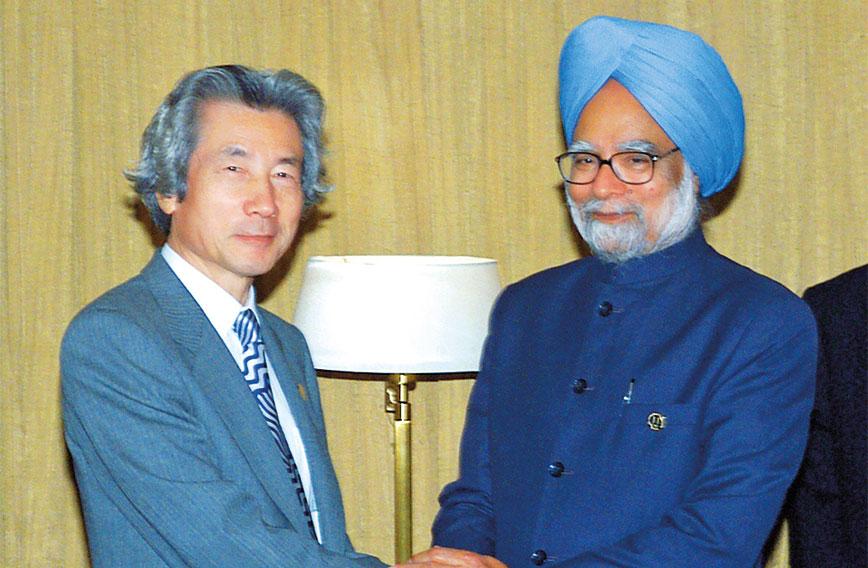

ON his first visit to India in 2005, Japan’s Prime Minister, Junichiro Koizumi, asked his host, Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, an interesting question. Observing that India is situated right in the middle of the vast Asian continent, Koizumi said that the part of Asia to India’s east had emerged as an arc of prosperity, while the Asia to India’s west remained mired in instability. The Japanese leader wanted to know which way India was headed.

Prime Minister Singh offered an optimistic view that India was increasingly ‘looking East’, learning from East Asia and integrating with it. The Indian economy was on a rising growth curve and India’s trade with East and South-east Asia was on the rise. Indians travelled increasingly to countries in the region, working and studying there. In short, suggested Dr Singh, India was well on its way to linking itself with the ‘arc of prosperity’, even as it continued to deal with the challenges posed by the Asia to its west.

Fifteen years later, an East Asian cannot be faulted for once again posing Koizumi’s question. Which way is India headed? Viewed from the East, India once again appears increasingly like its western and north-western neighbours, and less like the countries of the Far East and South-east Asia, with the exception of a couple of unstable entities like Myanmar. The India that was ‘looking East’, learning from it and hoping to catch up with it, has now been replaced by a more inward-looking India, obsessed with its internal contradictions. To the extent there is any interest in looking out within the Indian middle class, the gaze is once again turning West.

One must enter a caveat. Those familiar with Indian history, geography, society and economy have long recognized a distinction between two Indias. Not the usual divide defined by urban-rural and India-Bharat differences, but a divide between peninsular, sea-facing India and the India of the northern plains. Whatever the claims of Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath and his acolytes and despite changes of government across the Gangetic belt from Uttarakhand to West Bengal, India north of the Vindhyas remains not only economically less developed compared to peninsular India but also socially backward.

Seven years of the Narendra Modi government in New Delhi and five years of an Adityanath government in Lucknow have pushed the region further back in terms of social, political and economic stability indicators. The widening communal divide is only making matters worse. The recent anti-Muslim demonstrations in the nation’s capital once again draw attention to these divides and, more importantly, the social and cultural attitudes that underlie these divisions.

Seen from afar, this economically and socially retrograde India appears to East Asians as being more akin to Pakistan and Afghanistan than Thailand and Indonesia, not to mention Japan and South Korea. Most of my East Asian friends have said to me over the years that they feel more comfortable in Chennai, Kochi and Hyderabad than anywhere in the Hindi-speaking region. Bengaluru still has its appeal for East Asians but its increasingly communal politics and social conservatism could easily damage its global brand.

Mumbai, once viewed as “India’s Shanghai”, has become an increasingly provincial city in place of the global city it used to be and aspires to be. One would think the sea-facing and globalized Gujarat would have appeared as attractive to an East Asian as Tamil Nadu or Kerala, but it is not always so. While Gujarat, Maharashtra and Karnataka remain the more developed states, the political and social trends in these states may slow down their journey towards modernization of the East and South-east Asian variety. Hyderabad and Chennai remain cosmopolitan and hence popular with visitors from the East.

Many may question my assertions and I am open to correction; however, the fact remains that some parts of India are doing better than others and the divide may in fact be widening. Riding on improving economic, social and political indicators, peninsular India is continuing to link itself with Asia’s ‘arc of prosperity’, but northern and north-western India appear increasingly to be qualifying for membership of Asia’s ‘arc of instability’.

Going beyond purely economic, social and political factors, one must also consider the role of what may best be described as cultural factors. Peninsular India has acquired, with time, a culture of work and living that East and South-east Asians feel more comfortable with. Call them ‘rice cultures’ or what you will but there is a greater comfort factor there that is not yet visible in the non-rice cultures of the north and north-west. Indeed, all societies falling within the ‘arc of prosperity’ are essentially rice-based. All societies in India’s north, north-west and to India’s west are essentially wheat-based. If one were to divide Asia into rice and wheat-based societies then too India would be bang in the middle of Asia, with India’s rice-based regions advancing faster than its wheat-based ones.

Given the emphasis that state governments in southern India are placing on development, on the one hand, and the communal preoccupations of the governments in the Hindi belt, on the other, there remains the challenge of bridging the gap between these two Indias. Migration has emerged as a bridge between the two. The data on migration shows an increase in the movement of workers and employees from the north, north-west and north-east to peninsular India in search of employment. Would there be positive feedback on social and cultural attitudes from peninsular India to the Hindi heartland as a consequence, or would the regressive politics and conservative culture of the north percolate down south?

The world is watching where India is headed. Between 1991 and 2014 it had come to accept as given that India was closing the gap with Asia to its east. Prime Minister Modi’s enthusiastic outreach to Japan, South Korea and Singapore and his declaration that India would graduate from ‘Look East’ to ‘Act East’ generated much hope and optimism at home and overseas. However, during Modi’s second term in office events have taken a different turn and once again the Koizumi question is being asked, and not just in Japan.

Sanjaya Baru is a writer and Distinguished Fellow at the Institute for Defence Studies & Analyses in New Delhi.

Comments

-

Krishna Chadalavada - Dec. 7, 2022, 7:33 a.m.

I am not that sure that during Modi’s second turn, things are not looking dicey. The economy is not the only thing to look at, as important as it may be. India was rich and influential before invasions and colonization occurred. India fell on its face as it left the dharmic culture and became corrupt over a course of time, paving the way for subjugation by external forces. Your writer, Baru, I am sure is aware of these historic facts. Modi has had to face criticism, both from the so-called liberal as well as conservative forces. Actually, most of the blame for India’s economic poorness should fall on the previous dynastic rule after independence. It will usually take at least a generation or more of proper administration to get out of economic poverty. In a democratic country with many backstabbers, it will take time.