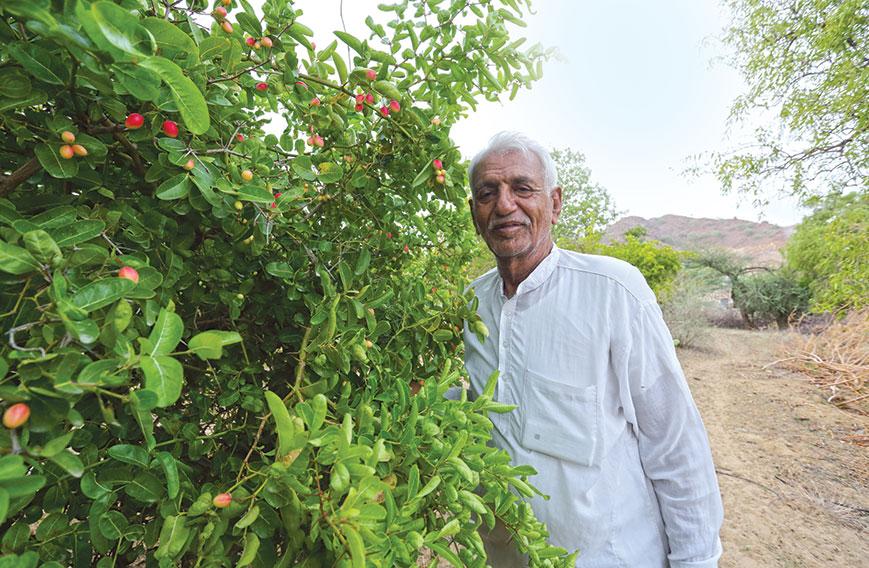

Chhogalal Soni poses with one of his fruit trees

An orchard in the desert

Civil Society News, Barmer

At 68, Chhogalal Soni has the gruff ways of someone accustomed to taking on challenges. A tall man, with gnarled hands and a burly manner, he has a diehard demeanour. In the first few minutes when we meet him it becomes clear that he is someone who likes to go the distance.

For 12 years now, he has been achieving what many thought would be impossible — growing an orchard of fruit trees in the sands of the Thar desert in Rajasthan.

We link up with Soni in Barmer town. But 12 km away at Marudi village is the theatre of action where Soni’s soul belongs. Here he has a 14-hectare farm, which was originally just sand, but now also has innumerable trees growing, almost impossibly, in the sand.

Locally, Soni has come to be known for his unusual passion to green the desert in ways that hadn’t been imagined before, not in Barmer at least.

Soni seems very much a man caught up in his own world as he enters his farm through two small crudely built rooms on the periphery.

Yet in his own taciturn style he lets it be known that he does like the attention he gets. Journalists like us, from Delhi, stopping by to meet him, are all part of a private high.

“I want the world to remember me for something I have done. Something impossible. So I decided to grow fruit trees in the sands of the desert,” he tells us.

But what is the secret of his success? How does he grow fruit trees in conditions where almost nothing else grows and rainfall isn’t in plenty though the occasional deluge does strike Barmer?

“It is hard work. It means spending long hours tending to the plants. Watering them, giving them nutrients. I’ve laboured here every day for weeks and months together. It is 12 years now,” he says.

Constant tending together with drip irrigation taking moisture to the roots of the plants seem to be the secret of Soni’s success. A network of pipes runs across the farm carrying water from a tubewell. There are a couple of farm-hands, but it is really Soni who puts humungous effort into maintaining a balance of moisture and nutrients and keeping pests away.

On our visit to the farm in summer, we find the fruit trees have been withered by two consecutive scorching summers. There are limes, some berries, karondas, a few coconuts and some struggling pomegranates. But it is evident that the trees are under enormous stress.

In good times the orchard’s list of successful trees has been impressive — mango, custard apple, guava, pomegranate, lime, coconut, jamun, chikoo and amla.

Soni has also managed to grow neem and gulmohar trees and some others too which we have difficulty identifying.

“They have been burnt by the sun,” says Soni. “The water table has fallen because we have had poor rainfall. If we pump out water for a few hours, the level falls so low that we have to stop,” he says.

Chhogalal Soni’s orchard of fruit trees in the sands of the Thar desert in Rajasthan

Chhogalal Soni’s orchard of fruit trees in the sands of the Thar desert in Rajasthan

It was July then and Soni was hopeful that after two bad years, it would rain this time. The farm is ringed by hills and so when it rains the water comes flowing down. The government had created two bunds and Soni has built three to slow the flow and let the water percolate into the ground.

This year the rains have been good — by expectations in the desert, of course. Soni tells us in October that the bunds have helped raise groundwater levels.

But Soni is now seriously looking at the commercial opportunities that his farm offers. He doesn’t want it to be a mere private passion, a boutique activity anymore.

He sees a great opportunity in amla or the Indian gooseberry, which has medicinal properties and enormous demand if cultivated to standard.

He indicated his amla cultivation plans when we went around his farm with him in July. But now he is taking them up in full swing. He has got high quality amla grafts, which he expects will give him robust returns in coming years. He similarly hopes to benefit from other trees with medicinal value.

Soni had a clerical job in the revenue department. When the post came to be abolished he set up a small business, which did well initially but then ran out of luck as the debtors increased and he finally never paid up.

It was then that he decided to work on the land that belonged to his family but was not being put to use.