Osama Manzar at the DEF office in Delhi

Osama Manzar

As India goes digital, equality in access becomes crucial. It is what makes the difference between giving people the benefits of growth or letting them fall behind.

It was with this thought that Osama Manzar founded the Digital Empowerment Foundation (DEF) in 2002 and has since worked with craftsmen and microenterprises to help them reach markets and customers.

DEF has through annual awards encouraged digital initiatives that have promoted inclusion and helped shape an ecosystem in which technology is used to serve the marginalised.

“A simple piece of information has to traverse at least 10 layers before an entitlement gets into the bank account," says Manzar. So DEF has created SoochnaPreneurs to help people get their dues. And Mera App tracks 2,000 government schemes. Manzar makes photocopying, emailing, lamination, filling up forms, and follow-ups available for the rural citizen.

Civil Society has watched DEF grow over the years. Below is a piece that appeared in the edition of August 2014. Read on.

The handwritten headline on a white board perched on a desk is eye-catching: ‘One Billion Connect’. Next to it sits. Osama Manzar, 47, founder of the Digital Empowerment Foundation (DEF), a non-profit in Delhi that works to bridge the digital divide in India.

Only 200 million out of India’s total population of 1.2 billion is digitally literate. Getting the remaining one billion connected is now a national goal. Manzar is part of an effort that involves governments, industry and the non-profit sector. But he is a frontrunner and proof of how much change-leaders like him are needed to turn social goals into reality.

Manzar’s bright smile hides his early years of rejection and failure. It was 12 years ago that he began to feel seriously bothered by the digital divide in India. Currently, he and his team at DEF are celebrated as passionate and innovative drivers of digital inclusion. He has crisscrossed the country, helping people in remote corners reap the benefits of information communication technology for development (ICTD).

DEF’s dream, says Manzar, is to connect all panchayats, schools, anganwadis, self-help groups (SHGs), small enterprises and all constituencies along with their elected representatives to the Internet. He believes it is possible by 2020.

What sets DEF apart is experience and knowledge. As early as 2004, when the digital divide was still being mulled, Manzar scouted India for best practices in ICTD. He examined Bhoomi in Karnataka, e-Choupal in Madhya Pradesh, Akshaya in Kerala, e-Seva in Andhra Pradesh, Drishtee in the North-East and Haryana, and n-Logue in Tamil Nadu, among others.

A year later, he launched the Manthan Awards to honour best practices in ICTD. “It is the Manthan Awards that really gave DEF the knowledge database for launching our own programmes,” says Manzar.

The Manthan Awards enabled DEF to know each and every noteworthy ICTD intervention taking place in India. As a result, DEF now has a database of over 5,000 such projects across India, South Asia and Africa and thereby understands what defines success in an ICTD project.

This is DEF’s reference point, its core strength, that has helped it implement projects working with governments, companies, global foundations, communities and NGOs. Over the years DEF’s footprint has grown and its revenues have doubled – from Rs 4.94 crore in 2012-13 to Rs 9.43 crore in 2013-14

“I can’t see revenues going down. We will only grow in future as everybody realises the importance of digital inclusion and digital literacy in solving developmental problems,” says Manzar.

Amitabh Singhal, a board member of DEF, who is also a director on the board of the US-based Public Interest Registry (PIR) and an ICT consultant, agrees. “We now have a problem – how do we cope with this growth and manage future growth?” says Singhal.

Then and now

DEF’s first major project was gyanpedia.in – financed by the Union Ministry of Communication and Technology in 2005. Gyanpedia aggregated content created by government schoolteachers and students and connected around 350 rural government schools to the information highway.

Since then, DEF has been mapping crucial underserved communities to whom digital literacy and connectivity would make a world of difference.

In 2005, it identified panchayats as an important area for intervention. Elected representatives, especially at village level, were not online and had no access to information, though they implement policies and schemes. India has 271,000 panchayats, representing some 545,000 villages. Connectivity would help decentralise administration, in keeping with the ideals of the 72nd Amendment which ushered in Panchayati Raj.

Thus was born the idea of the Digital Panchayat. In partnership with the National Internet Exchange of India, DEF has so far helped in connecting 500 panchayats. A functional digital platform and working station are created for each panchayat with Internet connectivity. Panchayat representatives are trained in IT skills. The objective is to provide a two-way flow of information so that people know about schemes, RTI, grievance redressal, employment and so on, and the local economy is helped through an e-commerce platform. Digital Panchayats were first started in Maharashtra and then expanded to eight states, empowering villagers and their elected representatives with information.

In 2009, the impoverished weavers of the famous Chanderi sari caught DEF’s eye. Chanderi is a town in Madhya Pradesh with historical forts and palaces. The saris provide revenues of Rs 65 crore in 2009, but Chanderi’s 3,000 weavers earned just Rs 2,000-3,000 per month. Now revenues are Rs 150 crore and weavers earn around Rs 10,000 a month. DEF set up the Chanderi Weavers ICT Resource Centre, a cluster network, in an old palace – Raja and Rani Mahal. It formed SHGs, introduced new designs and trained people to use Computer Aided Software (CAD). Around 500 young people were trained in conversational English and computer skills.

Chanderi saris now have a brand name, Chanderiyaan, and DEF is setting up an e-commerce site to enable weavers to access markets directly. The weavers of Chanderi saris now earn more, their dependence on middlemen has been reduced and they aren’t switching to wage labour.

Through the Wireless for Communities (W4C) programme, DEF has connected around 4,000 users in remote areas, using wireless technology and free spectrum.

In a village in Guna, Madhya Pradesh, connectivity drew children to school. Guna is one of the most backward areas in India, mostly populated by the Bhil and Sahariya tribal communities. Parents didn’t take schooling seriously and children were sent off to work. An earnest teacher was keen on computers being introduced for his students. DEF provided not just computers but training and connectivity too. Children, who were at first afraid to touch the mouse, flocked to school, happily browsing the Internet and opening email accounts.

To spread digital literacy among rural youth and provide vocational training, DEF has set up around 100 ICT and Internet-enabled facilities known as Community Information and Research Centres (CIRCs), jointly with governments, companies and NGOs.

Along with Intel, DEF is implementing the National Digital Literacy Mission (NDLM), an industry-led initiative that supports the Union government’s aim of creating at least one digitally literate person in each household in the country by 2020.

DEF has also helped create telemedicine facilities in five rural health centres in the tribal district of Baran where it supports a local NGO through one of its largest CIRCs.

Through its eNGO programme, it has enabled 3,000 NGOs and 200 small enterprises to go online with their own websites.

Alongside, DEF has undertaken initiatives in Bangladesh, Nepal, Pakistan, Bhutan, Kenya and Nigeria.

As a result, DEF has created a network of 3,000 organisations that address issues of livelihood, health, education, agriculture, water supply and environment.

“Osama and DEF have a wide network in India and outside,” says Dr Ajay Kumar, joint secretary in the Ministry of Communication and Information Technology. “They have this great ability to connect technology to rural people. They also understand how governments function so they can give very good inputs on how governments can work with civil society organisations. Moreover, because of their outreach capability they can implement projects that others cannot do.”

DEF’s diversity of programmes has much to do with its evolution over the years and the kind of funding it has received. But all its programmes have a single objective: to bridge the digital divide, make people digitally literate and ensure seamless last mile connectivity so that villages have a chance to develop.

Early days

Manzar says he is ‘almost’ a college dropout. It took him several years to graduate. “My father was an engineer with Heavy Engineering Corporation in Ranchi and always wanted me to become one. But I couldn’t get admission into engineering.” Instead, he reluctantly graduated in physics from Aligarh Muslim University and then found something he liked – journalism. He did a diploma course and then came to Delhi to find a job as a scribe.

For four years, he found none. He survived by living in the servant’s quarter of a DDA apartment complex just opposite the Jawaharlal Nehru University campus, and accumulated a debt of Rs 40,000. He didn’t want to ask for money from his father, who was convinced he was a wayward, good-for-nothing.

But he settled his dues after he got his first job in Down to Earth, a science and environment magazine published by the Centre for Science and Environment. However, two months later, he got sacked. His boss didn’t like him and kept making him rewrite copy, he says wryly.

Eventually, he got a job with Computer World as a reporter in 1994. That became the turning point of his life. “I interviewed hundreds of CEOs of top IT companies – N.R. Narayana Murthy, Shiv Nadar, Azim Premji and so on. That was when my passion for IT was ignited. I worked hard at understanding the Internet, which had just come to India in 1995, and the digital economy. I learnt a lot,” he says. And this time he was blessed with an encouraging editor, he says.

In 1997 he joined Hindustan Times Internet division and developed digitalHT.com, a news portal on the lines of rediff.com and yahoo.com. The division employed some 40 people. Then Chase Capital approached Hindustan Times and made an investment of $9 million for the portal, hiring a new CEO from Malaysia. “I knew I had to move once again,” Manzar says.

He decided to start his own enterprise in 1999. With a partner, he launched a media solutions and content management company called 4CPlus to help newspapers and publishing organisations go online.

“We soon had many clients and in just one year our turnover grew from Rs 20 lakh to Rs 4 crore,” says Manzar.

Alongside, he began writing and editing a book, The Internet Economy of India, which was published in 2001. “This was the first time I realised that poverty of information was the single most important impediment to development in today’s world,” says Manzar. “Even the poorest of the poor can be empowered to solve much of their problems if they become digitally literate and are able to access information bottom-up.”

So this became his mission. The idea of DEF was born with its tagline, Empowering People @the Edge of Information.

Manzar’s work as a journalist and as an entrepreneur, along with his book on the Indian Internet economy, finally got him recognition as an ICTD expert.

In 2003, he was selected as India’s representative on the jury of the World Summit Awards which seek to promote the world’s best in digital content and innovative applications within the framework of the United Nations’ World Summit on the Information Society (WSIS).

Today, he is a member of its Grand Jury that comprises some 35-40 experts nominated from among 174 country representatives. The task of jury representatives is to nominate organisations from their own countries which have done remarkable work in digital intervention for development. The Grand Jury makes the final selection. Manzar is also a member of several government expert panels dealing with ICTD. He is now the editor or author of five more books.

Manthan Awards

In 2003 Manzar spent a lot of time travelling to Dubai and then to Geneva, working for the World Summit Awards. It was a great learning experience for him as he came to know about various ICTD interventions around the world.

“I realised how such awards could become capacity-building platforms for creating knowledge networks. I began to work on launching the Manthan Awards to recognise and promote ICTD interventions in India and gradually in South Asia,” he recounts.

Meanwhile, DEF had become a functional entity in August 2003 and Manzar sold off his stake in 4CPlus to his partner. The money came in a few months later but Manzar gave it to his father to build a house – a rather pleasant way of redemption, of saying he had made it despite all the criticism he had borne.

The same year, he edited and published another anthology, e-Content – Voices from the Ground, through his media and publishing company, Inomy Media Pvt. Ltd, which he had launched simultaneously with 4CPlus as an Internet news portal and content house.

The book documented case studies of ICTD interventions across India and the world. He also used to produce a newsletter through this company that came to be very widely known and gave him an opportunity to write for global publications on a freelance basis. The money he earned helped pay his bills as he did not draw any salary from 4CPlus.

In 2004, funded by Planet Finance, a venture capital company, he travelled across India to learn first-hand about ICTD interventions in the country and subsequently began the prestigious Manthan Awards.

The awards recognise best practices in creative e-content. The jury carefully sifts through applications and ascertains the kind of digital interventions that have had the most impact on the lives of people. “It is less about technology and digital media and more about the right use of digital and technological tools,” states DEF’s website.

The Manthan Awards are given for the best initiatives in health, education, learning and employment, governance, agriculture, tourism and culture, women’s empowerment, inclusion, ecology and community broadcasting.

Last year, for the first time, the Manthan Awards included a new category – social media and empowerment. It was meant for those using Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, Flickr et al for campaigns for social causes. DEF recognised the power of social media, its democratic appeal and its ability to help in nation-building.

The awards went to Youth ki Awaaz, India’s largest online platform for youth to express themselves on issues they are concerned about. The portal even offers an internship programmme equipped with mentors to help the young express themselves with ease.

The Human Welfare Association was also awarded. It works with poor and minority communities in Varanasi, reaching out to them through SMS, word of mouth, social networking and meetings. The association provides education and livelihood.

Then there was Chinh Early Education, a web portal that promotes children’s causes and, with its blogs and videos, attracts some 400,000 page views. Vidya Poshak that provides financial help to poor but meritorious students was also chosen.

Also awarded was the People’s Movement for Drought Affected. Run by the Drought Help Group in Pune, this social media site links donors in cities to drought-affected villagers. You can donate money to build water tanks, desilt ponds or clear blockages in streams. The group works in eight districts of Maharashtra and does its work with accountability and transparency.

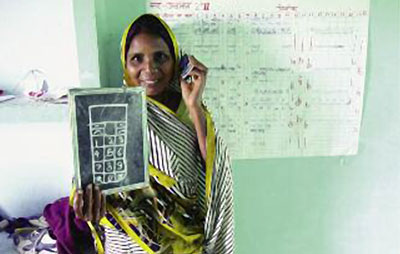

With the mobile phone becoming an important tool of digital empowerment, In 2010 DEF started the mBillionth Award to recognise and honour excellence in mobile communications in South Asia and help developers scale up their apps.

“The mBillionth Award is turning into a pool of m-knowledge, m-innovations as well as m-strategies and m-thinking with minds from India and South Asia all set to prove that the mobile is the next m-powering tool in South Asia,” says DEF.

In 2013, the winners were ZipDial Mobile Marketing and Analytics, the SEWA-SBI Financial Inclusion Programme that helps women become self-reliant by delivering social security schemes and the Adivasi Tea Leaf Marketing, a collective of tea leaf growers in the Nilgiris who have invented their own mobile app that processes orders for tea and creates a database in a paperless workflow.

DEF now has a database of 1,200 mobile apps. On 18 July it held a meeting where around 100 mobile and telecom players, including app developers, congregated to share their innovations for social and economic change.

“Osama and DEF have a lot of knowledge of what works on the ground, what business models work, what outreach models work and so on. They have tremendous reach in villages and among NGOs that work among the underprivileged,” says Ashutosh Chadha, Director, Corporate Affairs, Intel, South Asia.

“We are entirely project-funded. We have no corpus funds and nobody gives us any money to be spent generally over three years or five years, etc. Nor do we raise funds on ideas. We implement a project with our own funds, provide proof of concept and then seek funding to scale up,” says Manzar. “So far, none of our funders have stopped funding us. Instead, they are all willing to help us scale up further.”

Manzar’s affability, his knack of making friends and building relationships, has helped DEF’s growth. Its major funders from the government are the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, and the Ministry of Minority Affairs. It is also supported by Microsoft, Google, UNESCO, UNICEF and the European Union. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Ford Foundation, Sir Dorabji Tata Trust, Intel Foundation, Vodafone Foundation, Internet Society and Public Interest Registry also fund DEF.

“In our third phase we have been able to massively scale up our CIRC, W4C and eNGO programmes. We are now poised to realistically plan our ‘One Billion Connect’ goal by 2020,” says Manzar with optimism.

Comments

Currently there are no Comments. Be first to write a comment!