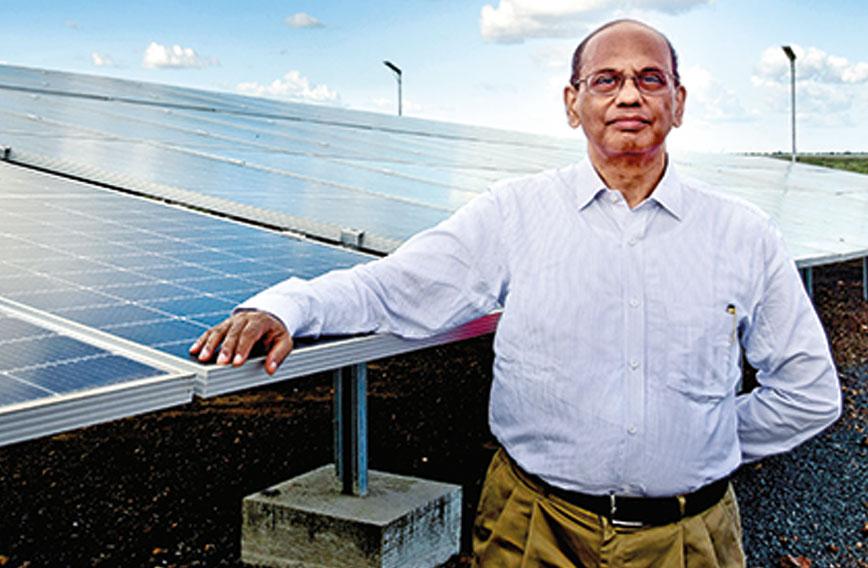

Ajay Mathur: ‘Last year, around $8 billion worth of investment went into the Indian solar sector’

‘Solar is now the cheapest power you get in India’

Civil Society News, Gurugram

WITH global warming, pollution and wildly unpredictable fossil fuel prices, renewable energy is the answer. India has played a leading role in the International Solar Alliance, but how successful has it been in facing up to the challenge of increasing solar power production capacities and bringing down the cost of solar power for consumers?

Ajay Mathur, CEO of the International Solar Alliance, says rapid strides have been made and that there is much to cheer about. Big-ticket investments changed the scale on which solar electricity is wheeled through the distribution system. Small producers have also been making solar power locally available. On the grid, solar power at Rs 1.99 per kilowatt hour is the cheapest power available at its sunshine price. The price when locally produced and distributed is higher but still lower than the price of fossil fuel power.

Q: India is pledged to installing 100 gigawatts of solar energy by 2022. Are we on course?

Actually, as a country, we have done relatively well. In 2012-13 we had zero megawatts of solar power. Today, we have crossed around 60,000 megawatts, or 60 gigawatts. This is a huge jump.

In 2015, we had committed that 32 to 35 percent of our electricity installed capacity would be from non-fossil fuel sources: hydro, nuclear, solar. We are already at about 38 percent. Solar and wind together account for something like 11 percent of the electricity that is fed into the grid. In 2015, solar was about zero percent and wind was about 4 percent.

This has happened largely because we got one thing right and that is how to add large-scale solar capacity into the grid. What we did was to move to a regime where new solar capacity is auctioned again and again and again.

We learnt that investors find it risky to invest in a project where land and PPAs (power purchase agreements) are not there. So, as much as possible, we try to put these issues in place before the tendering occurs. As a result, in 2015, the price of solar electricity was around Rs 12 per kilowatt hour. Today it is Rs 1.99 per kilowatt hour and is the cheapest form of electricity in India, obviously available only when the sun is shining. But it is the cheapest.

Q: That’s the sunshine price.

Absolutely.

Q: But what are the challenges?

One of the challenges we have faced is how do we get investments in solar and reduce the risks. The second challenge is what happens at night. In India, demand for electricity is increasing, whether it is day or night. The question asked is: Do I set up a solar facility and also a coal facility? Right now we have excess coal capacity which takes care of what is needed at night.

But the problem is that the contracts that distribution companies have with generators is that they pay a certain amount of money, irrespective of whether they buy electricity or not, because the person who has set up the generation plant has to pay the loan for that plant. He’s not going to set it up until he’s got some confidence that some money will be repaid. So that capital cost is repaid, no matter what.

And then if you buy electricity, you pay additional money for every kilowatt hour of electricity, which is essentially equal to the coal cost. So, because these people are paying the fixed cost, as it is called, they’re paying the fixed cost anyway.

Therefore, the real challenge is to bring down the cost of solar electricity to being less than the variable cost of coal power. The total cost of coal power is about Rs 3.5. Now, at Rs 1.9 per kilowatt hour it is in the range of variable cost. Generally, the variable cost varies between Rs 1.5 and Rs 2.1 or Rs 2.2 per kilowatt hour. We are now in that region.

Q: Who is buying solar power? You don’t have multiple choice suppliers at the domestic level as yet. So who are the big bulk users buying solar at a cheaper cost and therefore being able to bring down other costs of production as well?

There are two categories of buyers. One are the distribution companies. Some are buying more, others are buying less. For example, Karnataka, Maharashtra, Rajasthan buy a lot of solar electricity. These are also states where solar electricity is generated. So they have greater confidence that they will get the electricity when they want. But then you have a second category, the large users: for example, the Delhi Metro which buys electricity from a solar plant in Madhya Pradesh.

Q: And wheels it through the normal system that prevails?

Absolutely.

Q: Who are the key producers of our solar electricity?

The tendering route has gone in for large-scale plants. And as we’ve gone for larger and larger plants, we’ve got cheaper and cheaper prices. Who wins the tenders? It is a range of solar producers who compete and win these tenders. For example, ReNewPower and Greenko. They are in the business of producing solar and renewable electricity, setting up the plants and selling the electricity to potential buyers.

Q: Are there more big investments coming in?

Last year, around $8 billion worth of investment went into the Indian solar sector. This is large. Many investors we have spoken to have said that the greatest challenge they face is fear of depreciation of the Indian rupee versus the US dollar. They, therefore, have all kinds of mechanisms to hedge it. But, till now, India has not faced a problem in getting external or internal resources.

Q: Are you saying there are both borrowings as well as FDI in these projects?

Yes, there is borrowings, FDI, and equity. In India solar has become a very mature financial market.

Q: So, in seven years from 2015 to 2020, there has been an enormous maturing of the solar industry in how it produces, distributes, invests and funds itself?

That’s right and in the number and size of players in the market.

Q: Is there more competition happening as well?

A much greater degree of competition is happening between large-scale suppliers. You have a large number of players and the procurement system is open, transparent and based on lower and lower prices. The price declining to less than Rs 2 per kilowatt hour is a reflection of that.

We have not seen an equivalent growth in the rooftop market. It is estimated today that some 40 percent of commercial consumers who have put up solar panels on their rooftops own the property. They want to make sure they use it. They can’t get into the business of selling to consumers because the law says only the electricity company can sell it. Or I have to get permission from the electricity company to sell it.

There are third party companies putting up rooftop solar and selling at a price lower than what the consumer would get from the grid. For example, there’s a company called Fourth Partner Energy which has set up plants right next to us here in Gurugram. They sell electricity at Rs 4.4. If you buy from the grid, it’s Rs 7.5. Again, this is during the day. For commercial users, this is absolutely fine. In all these cases, the total electricity produced is less than the total demand. So the consumer buys from the grid as well as from the solar seller.

Q: Are we getting solar electricity to remote villages in India?

It comes into the grid so it goes everywhere. There’s no separate electron which is a renewable energy electron versus one which is a fossil fuel electron. The electricity distribution companies buy solar because it’s cheaper and then it goes everywhere, including to the villages.

The second answer is that in specific cases, for example, in Maharashtra, they gave land in rural substations to a company called EESL or Energy Efficiency Services Limited, which set up solar plants and supplies electricity during the day particularly to the agricultural sector. So, those villages are getting solar power during the day and the reliability is much higher. The electricity company, by their own accounts which they submitted before the regulatory commission, say when they got it from the grid, to the rural substation, it used to cost Rs 7.38. EESL sells it to them at Rs 4 per kilowatt hour.

So you can imagine the huge difference. What the Maharashtra electricity board said is, if I get this, I will make no losses. So we see both electricity and solar electricity coming in through the grid and going to all users as well as in this specific case being generated for the agricultural sector.

Q: What is holding us back from using this kind of distributed power more in the agricultural sector? Also, say, solar pumps.

There are two problems. The first is that the cost of a solar pump set is much higher than of a diesel pump set. So, while the electricity is cheaper, as far as the farmer is concerned, it is money out of his pocket.

That is why the government introduced the KUSUM programme to support farmers who invest in solar. They have various categories under which the farmer can buy the solar pump or several farmers can get together to set up the solar pump.

Remember, our farmers typically have small holdings. Therefore space going to solar implies that there is less space for farming. Because of the high price, it becomes very difficult for them to invest. Large farmers have been investing in solar. We have seen that happening across the board.

I’m a marginal farmer too. I put up a solar pump about seven years ago. It’s been working beautifully. I have now tried to get into the business of selling water to my neighbours. This is wonderful because everybody doesn’t have to dig a bore well.

Secondly, I will sell water through a pipe, because then I’m reducing the amount of transpiration. And my neighbour will also want to distribute it through a pipe because he also wants to get the maximum use out of that water. So it helps in the efficiency of water use. It’s happening, but very, very, very slowly.

An added problem is the lack of maintenance people. The government has launched a programme called Surya Mitra, in which they are training mechanics who can travel to villages and repair solar pumps. But this is a chicken and egg situation. You need a large number of solar pumps for the mechanic to make a living. And you need an adequate number of solar lights to make it financially viable for the mechanic.

Q: How can distribution be made more competitive and efficient and thereby bring down costs?

One of the key issues is that the price of the electricity that a distribution company buys from the generator has to be linked to time. Between 6 pm and about 10 or 11 pm, there is an increase in the load because lighting and air conditioning are switched on at that time. We need to ensure a higher price for peak demand.

Generators of hydro-power will need to invest in creating tail-end storage and the solar energy generator will have to spend on setting up batteries. They will invest only if there is a higher price available at times of higher use. So the first issue we need to address at the generation level is to make the prices time-dependent.

Q: Globally, we’ve had the COVID-19 pandemic, then there is the ongoing Russia-Ukraine war. How have these developments and the fluctuating price of oil affected the International Solar Alliance and its partners?

Irrespective of the pandemic, the addition of solar electricity and the money that has gone into the sector have kept increasing at a relatively fast pace. Last year, for example, approximately $200 billion was invested in solar energy, a very large amount. It is approximately the amount of money that was invested when a lot of fossil fuel energy installation was happening. What the pandemic did was to show that countries needed to create as much indigenous capacity as possible. Russian gas export restrictions impacted global trade and fossil fuels, more than anything else, and therefore, we have seen a fast increase in solar and in batteries.

Q: But hasn’t disruption in supply chains and so on affected manufacture?

You’re absolutely right. What has happened is that the price of a solar panel is higher now than it was three years ago. We are right now in the process of carrying out a very detailed analysis. But the first thing that it tells us is that because of greater demand, prices have gone up. Prices have also gone up because of supply chain constraints. The number of ships available are only so many, so it takes a ship longer to provide solar panels.

So what we’re looking at is a future where two things are very clear. Number one, by 2030 solar with batteries will be the cheapest form of energy in most geographies of the world. By 2050 it will be the cheapest with no competition. If this is so then demand will increase in each country across the world. And if supply chains are going to be a challenge we will need to create manufacturing facilities across the world. We are therefore putting out a paper next year, which will be looking at global manufacturing hubs in solar panels.

Q: How will this happen? Can you provide details?

You convert sand and silicon into polysilicon, then you convert that polysilicon into ingots, rods, cut it into wafers which become solar cells. And then several solar cells are put together to make the modules which you and I buy. So there’s silicon to polysilicon, polysilicon to cells, and cells to modules.

There are at least these three kinds of manufacturing that are needed. Silicon to polysilicon is an extremely cost-intensive, electricity-intensive business where electricity reliability has to be of the order of nanoseconds. This will occur in five to 10 countries at the most. But the polysilicon to cells conversion can occur in probably 50 countries. And cells to modules can occur probably in every country and certainly in every region.

The problem, as it appears in any other area, is where today’s price is. When you set up a new plant, this is where the price is. What happens to the difference? So, many countries have started offering all kinds of incentives to draw in manufacturing. Some countries say whatever technology is available, we will produce it here. Others say let’s look at tomorrow’s technologies. If you can do those efficiencies, which are more than what we get today, we will give you an incentive.

In India we have the Performance Linked Incentive (PLI). There is also the Inflation Reduction Act incentives, in the US there are tax credits and in the EU there is the solar power initiative. So we are seeing different kinds of incentives taking care of this delta, but also focusing on tomorrow’s technologies.

We will see over a period of time, 2025 onwards, a broadening of the manufacturing horizon across the world. This itself could also lead to prices being more stable than the sharp spike that we have seen in the past two years.

Q: Is India also emerging as a manufacturer of solar equipment?

With the PLI being provided by the government for cells, batteries, etc, there is, I think, 45 gigawatts of supply for which incentives will be put in. That much capacity is under construction. So, yes, we are emerging as a large manufacturer. And remember that these incentives are back-loaded. So they will be provided only if manufacturers are able to sell their products. They need to make products that are at least as efficient if not more efficient than today’s products.

Q: How is the International Solar Alliance helping developing countries to expand solar capacity?

The International Solar Alliance was announced at COP in Paris in 2015. It came into existence in January 2018 when an adequate number of countries signed it. It is a treaty-based organization. Today 109 countries have signed into it. Every week we have new countries joining.

Our goal is to make solar the energy of choice in all our member countries. When we talk to country leaders, they say, right, but why solar. We provide them information for solar advocacy. Like the study that we did which said that by 2030 solar would be the cheapest energy in most parts of the world. And by 2050 it will be the cheapest across the world.

Leaders tell us this is great, but who will do it. We have therefore started a programme to train people both at engineer level and technician level. You can train people, you can certify them, but then they also need employment.

We try to create that with the private sector in various countries. For example, in Namibia and, recently, Venezuela. The course content is very closely related to what the local solar association says. There are three certification standards, the Indian standard, the US standard and the EU standard. We certify them so that they can be employed. Hopefully, the time lag between certification and employment isn’t large. We provide similar training to policymakers.

Third, and I was very surprised at the very quick uptake, are bankers. Because local money is needed. If a banker doesn’t know anything about solar, how on earth is he or she going to lend? Across the world, solar training for bankers has huge uptake. In the last session, we trained about 1,000 people.

Comments

Currently there are no Comments. Be first to write a comment!