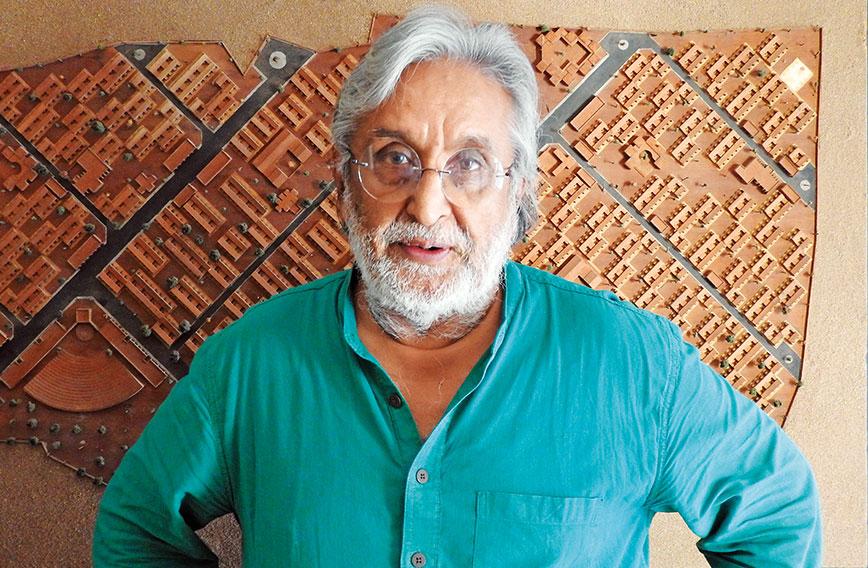

Kirtee Shah: 'The quality of housing produced in the last 30 to 40 years has given a bad name to affordable housing'

‘Affordable housing needs better processes’

Civil Society News, New Delhi

Affordable housing allows people with low incomes to live decently and stay healthy. The idea has been moving along in fits and starts with policy spawning initiatives in design, construction and finance. A big push came in 2015 with the Modi government’s Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (PMAY).

But much remains to happen and to get a perspective of what has been achieved and the challenges ahead, Civil Society spoke to public-spirited architect Kirtee Shah, chairman of KSA Planning Services in Ahmedabad.

Shah has devoted his life to improving habitats. His views are sought on sustainable urban development. He is also founder-director of the Ahmedabad Study Action Group (ASAG), a public charitable trust.

Shah has recently written to the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs, asking for a new National Commission on Urbanisation to be set up as a think tank that will take a comprehensive view of the problems plaguing Indian cities and suggest ways and means to tackle urban issues based on Indian realities, culture, climate and so on.

It’s almost a decade since we started talking about affordable housing. What have we really achieved in terms of policy, numbers and impact?

In the past four years an extra push has been given to affordable housing with the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (PMAY). I am not saying nothing happened before that, but the real push has come from that programme. The scheme is a good idea, whatever its weaknesses or ultimate outcome.

Building 20 million houses by 2022 may look rather ambitious. You are talking about constructing something like 7,500 houses per day. The question is — do we have the delivery systems, the resources, the institutions to cope with this. Since we don’t, we also have a problem.

But the political statement that we have got to house everyone in this country is an important one and I would like to state that upfront.

Secondly, the government has taken steps in terms of incentives, inviting the private sector, a fairly good design of the PMAY, tax concessions, subsidies and an interest intervention. There is an attempt to bridge the affordability gap.

But there are a number of issues. Achievement has not been very significant. After three and a half years of the PMAY, not more than two percent of affordable housing has been achieved in terms of actual numbers. Despite incentives to the private sector, the market hasn’t really geared up, though there are projects here and there.

I have been working with a client who does large-scale housing. He has a 100-acre site in Chennai. Knowing my interest in affordable housing, he reached out to me. But he wanted to do affordable housing on only two acres. I asked him why when in Chennai there is a big demand for affordable housing. I am not certain about the market, he said. Despite the concessions and subsidies I don’t think I can sell that much, he said. So, incentives haven’t got the market moving.

Do we need a change in mindset?

See, there are other aspects. It’s not only about production of housing. Housing has backward and forward linkages. A large target like this one brings in certain distortions. You end up making hasty decisions, reporting becomes inaccurate, you tend to inflate your achievements. I am talking about the public sector.

The biggest casualty of this large target is that you aren’t able to devote enough time to processes. And housing at all levels in all forms is a process-driven product. It requires time, concentration, many players working together, systems, apart from land, finance, market and unified services.

With stiff targets, quality suffers and processes aren’t factored in. I think this is one of the major worries we should have. We need to really examine the kind of housing that is coming up in terms of design, construction, quality of infrastructure and so on.

Are you talking mostly about housing stock created by the public sector?

No, both. If you look at the last 50 years, the private sector hasn’t touched affordable housing. Affordable housing has essentially been the domain of the public sector. And the quality of housing produced in the last 30 to 40 years has given a bad name to affordable housing, low-income housing and small housing. In fact, low-income housing has become synonymous with low-quality housing.

The private sector was happy building for the upper middle class and the middle class. There was a market and clients with money which is much easier than dealing with people who don’t have money.

The private sector is beginning to get into affordable housing, although slowly, for three reasons. One it is a very large government programme which has been declared an industry. There are tax concessions and other advantages. Secondly, there is a glut in the upper end of the market in most cities with apartments lying unsold. Thirdly, they are beginning to see a future in affordable housing and seeing it as a huge market.

We see housing as a driver of the economy. Shouldn’t affordable quality housing be housing for everyone?

This is an important point. If one is talking about housing the whole country then you have to examine the backward and forward linkages of housing: employment generation, contribution to GDP, skilling of craftsmen, delivery systems, institution building, innovation in design and material … if all this happens on a large scale, you get the economy moving.

Public health is so important. Statistics talk about the costs of improper hygiene, lack of water and sanitation in terms of ill health and loss of wages. Good housing could take care of most of this.

But where does this figure of 20 million come from? Eighty percent of the housing deficit we are talking about, 18.4 million in urban areas, is essentially categorised as congestion. Another 0.99 million or five percent of houses are non-serviceable… 2.7 million or 12 percent is of absolute housing and 0.53 million or eight percent are homeless.

What constitutes a deficit and which deficit are we trying to close? If 80 percent of the housing we are talking about is basically congested housing, do we need to build full houses to take care of that? Maybe we could improve those rooms and toilets.

According to the last census the vacancy rate in several cities is 12 to 14 percent. So the houses exist but they are locked. A 10 to12 percent vacancy rate in a city like Ahmedabad with a population of six million means a vacancy rate of about 150,000 houses. These houses are built, locked and not in the market. You have to look at all these options.

How would you address the issue of slums?

We need a change in mindset and strategy. The Odisha chief minister, Naveen Patnaik, has announced that his government isn’t displacing slum-dwellers but empowering them by giving 4,000 families land rights.

Slums aren’t a problem but a solution and slum-dwellers are a resource. Mumbai has millions of people living in slums. If these people had not used their ingenuity, if they had not dared to encroach on land and create whatever quality of housing they could, they would be living under the sky. They didn’t come to Mumbai for housing. They came for jobs, services, livelihood, education. Dharavi is not a slum of poverty. About 83 percent of its residents are above the poverty line. The problem is that the system did not create affordable housing and therefore they ended up living in slums.

These houses should not be bulldozed but improved and built upon. Now if you accept this then there are strategies which can be utilised very well — like in situ slum upgrading. You don’t bulldoze slums. Instead, give them secure land tenure. It could be in the form of land rights, property rights, legal rights, whatever.

This housing has been made by them. If you ensure they won’t be evicted, they will further invest and improve their homes. What prevents them from investing is the Damocles’ sword of eviction. You don’t have to look for land. It already exists, it is occupied and being used. If you accept in situ slum upgrading as an approach, provide secure land tenure, precipitate the municipal corporation to provide services on payment, if you provide some kind of loan assistance to people to improve their housing, slums will be refurbished by the next generation and in 15 years they will become fairly livable.

Slums are very densely populated. You do need to create spaces, especially for infrastructure and services. If you were to selectively remove 20 percent of houses in slums you will be able to improve living conditions.

In Mumbai about six percent of the land is being populated by 50 percent of the people. This land is in any case non-productive and your political processes can’t allow you to throw all those people out. So, if this policy of upgrading slums is accepted you can resolve the issue of slums.

Indonesia has done this in a big way. In their cities, Jakarta and Bandung, in the 1970s and ’80s, they helped people improve their shelters, built infrastructure, roads, provided services and they now have reasonable neighbourhoods.

We should be talking about Mumbai not as a Shanghai but as a better-housed, more equitable Mumbai.

But land is expensive in the city.

You asked about land strategy. One is to unlock land for creative purposes in order to improve slums. Second are town planning schemes and I think Gujarat and Maharashtra have done this fairly innovatively. The third, and China has done this in a big way, is through land value capture. You direct resources to villages. You bring in rural industries, infrastructure and services and ensure the village works as an extension of the city in terms of land supply. You link those areas to cities. Connectivity is very important.

You can’t talk about housing in isolation. It has to be with mobility outreach. Transport planning is an integral part of housing. It brings distant land to the city.

Do you think a rental market in affordable housing is worth exploring?

We have not paid enough attention to rental housing. Let’s look at the role that rental housing plays in developed countries. The numbers will surprise you. In Germany, 60 percent of its people are on rental. In Berlin, 89 percent of people live in rented accommodation. In Rotterdam 49 percent of people are on rental. In New York it’s 55 percent. Compared to that, Delhi has 28 percent of its people on rental.

The biggest villain is the Rent Control Act. It’s created such absurdities. A property that could earn Rs 3 lakh a month is still out on rent at `12,000 per month. Landowners and property owners can’t invest in maintenance. The Act brought down the quality of housing very badly, especially in the chawls of Mumbai.

Of course the biggest culprits were the public sector which did a fair amount of rental houses in the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s but they mismanaged them. The Gujarat Housing Board mismanaged their rental housing so badly that ultimately they had no option but to sell it.

So you think this is a possibility we should seriously explore?

We must do this. You need all types of housing in an urban space. Besides, we haven’t been able to bridge the affordability gap. We also have a younger generation who are beginning to earn but do not have the savings to invest in a property. They are also very mobile.

State governments could create greater housing stock and see that it is managed well. I think it will happen in the next three or four years since the housing programme isn’t growing so fast.

If I am earning Rs 10,000 a month, I will have to pay Rs 5,000 to Rs 6,000 in monthly loan instalments. But if I can get rental property for two years I am very happy till I can reach a stage where I can afford to invest. There is a large number of people who would fit into this bracket.