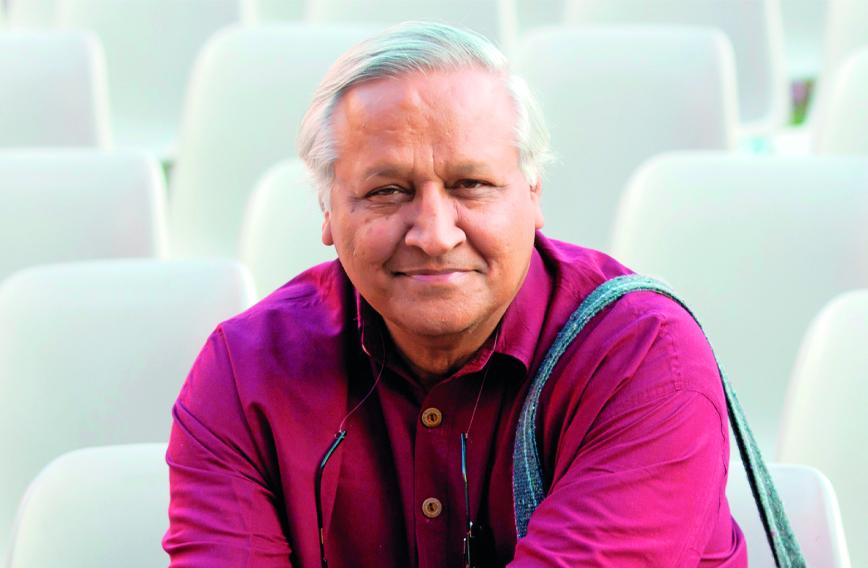

Bunker Roy: ‘I am happy to be a catalyst for non-violent ideas’

‘People with degrees do little to solve rural problems’

Civil Society News, New Delhi

THE Barefoot College has completed 50 years, a signal achievement for any voluntary organization. Based at Tilonia, in a corner of Rajasthan, it has found recognition for itself across the world.

By training rural people, particularly women, to address their own development needs, the college has shown that learning is not just about degrees. So much more impactful are the practical skills, innate abilities and traditional knowledge of communities. Acknowledged and put to good use, they can be empowering and transformational.

The barefoot in the college’s name defines its spirit. Helped to discover themselves in their own environment, people without a formal education set up solar facilities, design and construct buildings and create elaborate water harvesting networks. Everything becomes possible. Being rural doesn’t mean being backward. To the contrary, village practices run deep and have their own sophistications.

Behind this wonderful idea all these years has been Sanjit Roy, better known as Bunker. Why Bunker, you might ask. Because his brother was Shanker. There was a bubbly insouciance in his early years. Everything rhymed.

When you are born into influence and some wealth, chances are that you will continue to see the world in just one way. Not so Bunker, who as a young man slipped out of his gilded zone to live and work in villages in true personal reverence for Gandhi’s ideals.

Opting out was difficult to explain because Bunker had a whole lot going for him. Doon School. St Stephen’s College. India’s national squash champion three times. A swashbuckling cricketer. A medal-winning swimmer. A charmer on campus.

But then came a detour from which he never really returned. He joined other young people in answer to JP’s call to come to the aid of famine victims in Bihar. The poverty and deprivation he saw, perhaps upfront for the first time, so disturbed him that he came back convinced that all he wanted to do was work in rural India.

That was in the late 1960s and a few years later he ferreted out Tilonia. The Social Work and Research Centre (SWRC) was then set up by him and Aruna Roy. The Barefoot College followed. The Roys were youthful and out to change India. The spark hasn’t left them though the years have added up.

In the past 50 years much has changed. The Indian economy is the toast of investors. But the vision on which the Barefoot College was based remains relevant. Rural India deserves much more recognition and respect than it gets.

Our interview with Bunker Roy as it unfolded between Tilonia and Gurugram:

Q: When you chose Tilonia to set up SWRC what were you thinking? A tiny, unknown location in such a large country… what sense did it make to you? What was your dream?

From 1967 to 1971, I was blasting 500 open wells in Ajmer district for an organization called the Catholic Relief Services. I was taken to Tilonia by a colleague of mine, Meghraj, who was a rock-driller. I was thinking of a small project focusing on water because water is a big problem in the desert. We did a groundwater survey of 110 villages and we found the situation critical.

Q: So it was specifically to address the water problems of a desert area? Has Tilonia’s water problem been solved?

Tilonia’s water problems will never be solved in this lifetime because the population has increased and the water level has gone down from 60 feet to 300 feet. I was really addressing the water problems of 100 villages around Tilonia. The demand for water for agriculture, drinking, commercial farming has increased manifold — so there will always be a shortage. What remains to be done is to be disciplined in use of water. Water management is more important than ever.

Q: You mention rock-drilling, which would mean groundwater. Over time you seem to have found more merit in water harvesting. Was your learning from this?

Yes, it was my learning. Between 1974 and 1989 we believed the engineers — that the drinking water solution would be through handpumps. But we learnt from an old man in the village that the long-term solution to the water problem is in rainwater harvesting and not exploiting groundwater.

So today we have a network of rainwater harvesting tanks all over Rajasthan and other states. We collect 90 billion litres of rainwater through tanks, nadis and dams.

Q: Generally, a whopping 50 years later, when you look back is it with satisfaction, regret…?

It is a matter of great satisfaction that Tilonia has managed to change the mindset of people towards literacy and education. For 50 years, we have shown the importance of rural quality in education as against importance being given to degrees and qualifications. From the very beginning, we were convinced that paper degrees do not guarantee professionalism and competence. In a meeting called by the Mind and Life Institute in Zurich in 2011, I gently challenged His Holiness, the Dalai Lama, when I said, where is it written that just because someone cannot read or write, he or she cannot be an engineer, a health worker, a communicator, an educator. Where is it written, Your Holiness? Your Holiness, do you agree?

The regret is that even when I worked at the highest policy level in the government, in the Planning Commission (1984-89), when I took one rupee as consultancy fee, I did not manage to convince people that this was the rural solution for India.

Q: How can someone be an engineer, doctor, nurse or optician without knowing to read or write? Surely some distinction must be made between the uses of traditional knowledge and modern science? Are you saying we don’t need modern education at all?

I don’t understand how someone can be an engineer or nurse without hands-on knowledge and competence. There has been traditional technology without degrees that has kept the world going.

In every isolated village of India and abroad, there are women who are midwives who help, often in complicated cases, where hospitals are far away. Midwives are also opinion-makers and hold considerable influence over other women. It was only when we understood their strengths and some weaknesses and worked with them that we understood women and that empowering them meant respect and dialogue.

Men and women who have knowledge and practical experience in engineering and medicine have kept the rural world going. They did not have the opportunity to read and write, but they have common sense, intuition, improvization and gut intelligence. They are highly respected, sought after, in their villages, and are able to apply their skill without anyone asking to see their degree.

The spot for drilling a bore well or digging a well is even today decided by a water diviner, with a high percentage of success. It is fortunate and somewhat extraordinary that there are some geologists who are also water diviners!

The danger comes when a graduate with a paper degree (and no real education, considering the ethics of education and educational institutions) in engineering, or in medicine or what you call modern science, is let loose on communities.

Yes, I am saying categorically that what goes by the name of modern education does not fulfil or satisfy genuine rural needs. Tilonia’s success in using semi-literate and illiterate people is a challenge to modern technical and professional education. Degrees have to be validated with proven competence. We are still waiting for that to happen.

Q: What difference do you think you have made to the country, to Tilonia itself?

I would like to think that the work on the ground has motivated and inspired lots of people from different walks of life to follow the Tilonia example and claim that they got the inspiration from Tilonia. This includes, I think, hundreds of people all over the world.

Q: Put this way, it would seem you are happy to have been a catalyst for new ideas. After all “hundreds” doesn’t add up to much in terms of the world. Is that then the role social activists like yourself should be satisfied with? Drivers of ideas and solutions in the hope of larger change at some time?

I am happy to have been a catalyst for strong, innovative, down-to-earth non-violent ideas that have never been tried before. Tilonia has always provided the space to try these ideas and even if some of them have failed, we will continue to provide a platform for innovation to young people.

I do not call myself a social activist but a social entrepreneur and I am never satisfied with results because there is always scope for improvement. The whole idea of the woman catalyst bringing fundamental social change at the village level was at the forefront of Tilonia’s engagement.

For instance, women hand-pump mistris and traditional midwives participating in the movement for generating awareness about sati and other social issues, minimum wages, untouchability.

Fed into government, they have led to larger changes in government policy and programme. The innovation with school education with untrained but committed local teachers led to the Rajasthan government’s Shikshakarmi, a programme for schools in remote areas that was run by literate but untrained teachers from the community. They were appointed as government teachers all over the state.

The work of identifying Dalits and backward class women with leadership qualities led to the Women’s Development Programme of the Rajasthan government — a landmark programme that spawned many other such programmes in India. The Lok Jumbish programme was also the result of experiments tried in Tilonia by the Rajasthan government.

Tilonia’s battle for minimum wages for famine relief works, based on the ground-breaking leadership of a Dalit woman, Naurti, resulted in a famous judgment in a PIL in the Supreme Court in 1983. The order by Justices P.N. Bhagwati and R.S. Pathak established that no work site in Rajasthan could pay less than the minimum wage structurally.

Q: You know, you come from such an elitist background. Doon School, St Stephen’s. What was the point at which you changed direction?

When I went to the famine in Bihar, in response to an appeal by Jayaprakash Narayan. The poverty, starvation, the helplessness, the cruelty — there was an India that I had never seen. And neither St Stephen’s College or the Doon School exposes its students to such experiences, which I think is a great shame.

Q: What did it take to gain acceptance and involvement with marginalized communities? How did you strike a chord?

I was not interested in gaining acceptance from the community I was working with. Rather, my aim was to select community leaders from these castes and villages to be my eyes and ears. So all the work that is reflected is actually the work of these people on behalf of Tilonia.

My job was not to become a neta and speak on behalf of communities, but to identify potential leaders in these communities who would then implement all the programmes and projects that have been done over the past 50 years.

Q: But surely your elitist background made it easier to access funds in the corridors of power. You were their neta or, at least, their spokesperson in those settings. They could not have done it on their own.

Tilonia must be one of the few civil society organizations that initially received more funding from government than from foreign sources. This is because I was in school and college with bureaucrats who were in the corridors of power.

So, access to funding was relatively easier. Between 1975 and 2000 we had access to funding from important ministries, including those of external affairs, science and technology, education, rural development, etc. I agree I was often the spokesperson in these settings. And, occasionally, when they wanted to try an idea bypassing the system, they would approach me.

Q: Do traditional technologies make a difference to development? And if those technologies and practices already existed why would you need SWRC or Barefoot College?

The job of Tilonia is to demystify technology and bring the most sophisticated technology into the hands of very poor people. It would be these people that would be controlling the use and spread of technology. This should ultimately include Gandhiji’s last man and woman.

Q: Which technologies have been improved and promoted and how would you rate their success?

Solar technology, water management technology, dryland technology, waste management technology are some examples.

Q: In recent times you have worked to promote solar power. Was this a turnaround in your thinking?

No, the two campuses of Tilonia were first solar electrified in 1986 and 1990. We have always promoted technology that will lead to the welfare and development of people at the level that matters most. Today there is the model of the Solar Mamas, recognized by the prime minister of India, of training illiterate, rural grandmothers from non-electrified villages all over the world, with the support of the Ministry of External Affairs (which supports the travel and training cost). Tilonia has trained over 1,700 Solar Mamas in 96 countries.

Q: For someone who has done so much, you must have regrets. What are the mistakes, missed opportunities that haunt you?

I regret that I did not manage to convince civil society groups to adopt a code of conduct in spite of a national dialogue to voluntarily adopt the values of simplicity, austerity, transparency and accountability in their working. The smaller organizations were all for it, but the larger foreign-funded organizations shut it down.

I also regret that the bottom-up, Gandhian, barefoot approach has not been adopted by civil society organizations on a large scale. In 1974, however, we had this scheme of inviting young boys and girls from different parts of the country to stay an indefinite period, pick up some confidence and competence and then help them start their own organizations in the states they came from. So we have a network called Sampda of 20 barefoot colleges in 16 states in India, reaching over two million people.

Q: And what’s it that you cherish personally over and above all that can be quantified and put in an annual report?

Aruna Roy’s contribution to Tilonia.

Comments

-

Anjana Sharda - Sept. 5, 2023, 2:13 p.m.

With due respect, and as it’s teachers day also today, which is incomplete without students, and most importantly because it lights the ray of hope, just thought to share from personal experience that there are many out there who take up studies even after they are done with their corporate career and they have crossed “expected age” to pursue higher studies only to Kaur some positive contribution in societal development.

-

renuka savasere - Sept. 2, 2023, 2:29 p.m.

I am among those hundreds of thousands that you have influenced & this is my chance to say- thank you bunker roy!