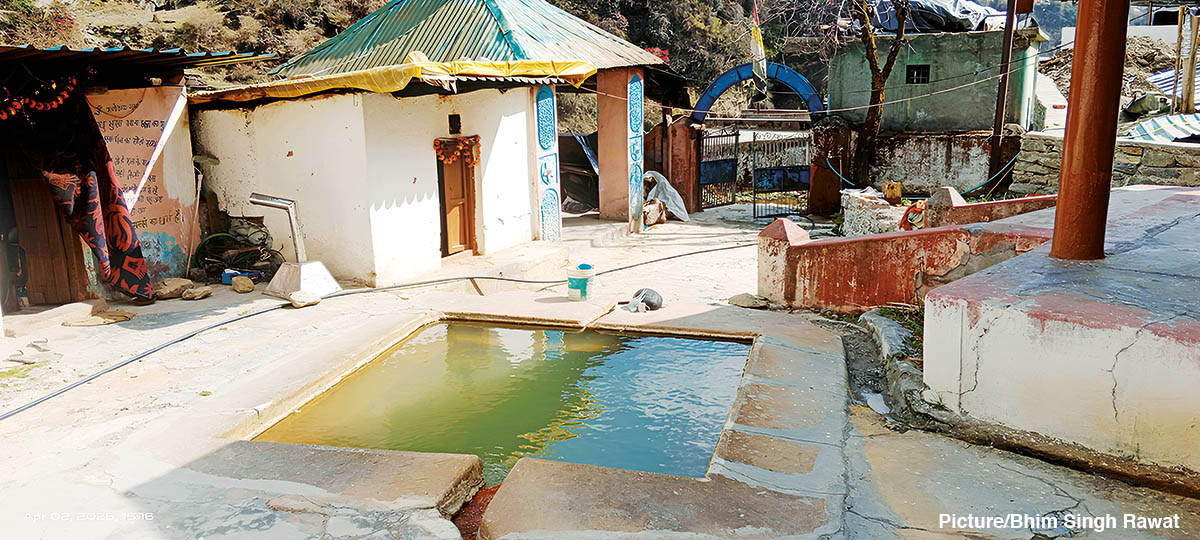

A natural water source tapped at an eatery by the road near Mason village in Chauthan Patti of Thalisain block of Pauri Garhwal, Uttarakhand

Himalayan springs are dying

Venkatesh Dutta

SPRINGS that have for centuries met the domestic needs of people in the Himalayan region are now disappearing, leaving them without a dependable natural source of water. Known to be perennial, the springs provide cool, clean and sweet water that gurgles out of mountainsides. From the cold deserts of Lahaul-Spiti to the moist landscape of the northeast, springs have been intrinsic to local cultures. They have been intrinsic to the way of life of mountain communities.

I remember water emerging from a small spring even in summer just upstream of Rishikesh town on Tapovan road. The water was potable and flowed 24/7. Local communities filled water in buckets and tumblers for drinking and cooking. The source was nowhere to be seen. Water, minus any pipe, gushed strongly from pores and cracks. A 15-litre bucket could be filled in just two minutes.

This spring dried up in 2015 due to construction projects happening all around the town. I have also noticed that many springs now yield less water compared to 20 years ago. Many permanent springs have become seasonal and some have dried up completely in Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand.

In Nepal and Uttarakhand, I have noticed that several spring-fed rivers and streams are drying up since their source springs have ceased to flow. Many spring sources have shifted from higher to lower elevations, making it harder for people in upper areas to access water. Women are forced to fetch water from alternative sources or far-off places, sometimes even spending money on buying water cans. They are also trying to adapt to reduced water consumption and often face social conflicts or conflicts at home. Not just humans, animals are also affected. Their natural watering holes inside forests are now becoming seasonal or drying up completely.

NITI Aayog’s Working Group on ‘Inventory and Revival of Springs in the Himalayas for Water Security’ expresses serious concern over the depletion of Himalayan springs, vital for the region’s water security. According to this report, approximately 50 percent of perennial springs in the Indian Himalayan Region (IHR) have either dried up or have reduced discharge, affecting thousands of villages dependent on such water sources. The decline in the availability of spring water has led to acute shortages for drinking and domestic use, impacting livelihoods and leading to challenges such as increased outmigration.

In the mountains, snowmelt and flowing river water are not readily accessible. Springs are the primary source of high-quality drinking water for thousands of villages in mountains and high-altitude areas. In Uttarakhand, Himachal Pradesh and Nepal, it was common practice to endow springs with decorative features like lion- or bull-shaped spouts made of stones. These dharas were often built near temples and key public places, serving both practical and cultural purposes.

LIFE CYCLE OF A SPRING

|

| Springs at Gangnani en route to the Yamunotri shrine before merging with the Yamuna at Burnigad in Naugaon block of Uttarkashi |

Rising temperatures, decline in snowfall and rainfall, construction of roads, buildings and highways, and excessive drawing of groundwater have caused irreversible damage to such fragile ecosystems. As snow cover decreases, springs rely more on rainfall. This leads to less water seeping into the ground, slowing down the recharge of aquifers and reducing the discharge from the springs. Deforestation, large-scale land use modification and soil erosion are hampering the water-holding capacity of the hills, causing off-season flow in streams. Hundreds of communities which depend upon springs for their daily chores are affected. About one-fourth of active springs have become seasonal instead of perennial, depending on the monsoon. Road and infrastructure projects are the main cause of springs drying up.

Just as streams have watersheds or catchments, springs have springsheds from where water is channellized into them. Springs rely on groundwater sources and their perennial flow is dependent on these subsurface reservoirs. Sandstone, fractured limestone, and unconsolidated sand deposits and gravel formations create aquifers in hard-rock areas. These formations act as natural reservoirs, storing and transmitting water through springs. When rainwater seeps into the ground through cracks and gaps in the rocks, it refills the underground reservoirs. As more water enters, it pushes the stored water through these gaps in the rocks. This natural movement brings the water to the surface, forming a spring.

Uttarakhand has a strong tradition of water conservation. Springs are locally known as naula, dhara, khal, gul, simar and dhan. A naula is a traditional water structure made of stone, resembling a small hut that shelters a spring. Its floor is left porous to allow water to seep in naturally. Naulas are considered sacred and deeply connected to local culture and religious practices. Villagers often treat them like temples. A gul is a water channel that diverts and supplies water from a source — often underground but sometimes from surface flows.

Rituals like weddings and naming ceremonies have long been connected to naulas and dharas. In Kumaon, a newlywed bride first offers a ritual prayer at the village naula or dhara upon arriving at her husband’s home, symbolizing deep respect for the community’s water sources.

Since spring water emerges on the surface naturally, it does not get much attention. While designing water supply schemes in hilly areas, engineers lay more emphasis on developing artificial reservoirs and lifting water from pumps and forget or overlook local numerous spring sources that could be sustainably managed.

A stream flowing through Chanfi, a seasonal tributary of the Gaula river near Bhimtal in Uttarakhand

A stream flowing through Chanfi, a seasonal tributary of the Gaula river near Bhimtal in Uttarakhand

The Government of India (GoI) launched the Atal Mission for Rejuvenation and Urban Transformation (AMRUT) as a water-focused national urban mission in 2015. The objective was to provide universal coverage of water supply in 500 mission cities. The first phase of the mission was extended till March 2023. Then, AMRUT 2.0 came up in 2021. After that the Jal Jeevan Mission (JJM) and Har Ghar Jal Yojna were launched. The Ministry of Jal Shakti began the Jal Shakti Abhiyan to promote water conservation and water security in several water-stressed districts.

What we need is a full-fledged scheme that will adopt a nature-based approach for spring rejuvenation in the Himalayas. Traditionally, village water sources followed a natural gradient, allowing percolation into soil and replenishment of underground aquifers. The modern pipeline system bypasses this natural recharge process, leading to faster depletion of groundwater tables.

Increased surface water withdrawal reduces seepage into the soil, lowering spring rejuvenation rates in the long term. Villages — where water scarcity has always been a challenge — still struggle for reliable access to potable water, while uncontrolled extraction from springs and streams in water-rich areas is depleting sources faster than their recharge rates.

TAPS AND PIPELINES

Situated in the buffer zone of the Dudhatoli Reserve, Chauthan Patti, a cluster of approximately 72 villages, is rich in natural endowments. It has lush forests and water resources. The region forms the initial catchment of the Nayar and Ramganga rivers and is drained by numerous first-order streams. Until about two and a half decades ago, potable water was primarily sourced from natural springs, developed into panyaras in most villages. Later, government schemes introduced stand-post connections, along with separate diggis (small reservoirs) designated for Scheduled Caste communities. These, too, were fed by the local dhara or choyi (spring-fed structures).

A spring-fed drinking water source called panyara in Mason village on the periphery of Dudhatoli Reserve Forest in Pauri Garhwal

A spring-fed drinking water source called panyara in Mason village on the periphery of Dudhatoli Reserve Forest in Pauri Garhwal

The number of standposts increased under the Indira Gandhi Rural Drinking Water Scheme around 2005, and over time, villagers extended these connections to households on their own. Despite this, for most of their drinking water and daily household chores, people still relied more on panyaras and diggis. With the growing number of rural development schemes, spring-based supplies were enhanced through the construction of tanks and pipeline extensions. However, this gradual infrastructural shift led to the neglect of traditional sources.

With the introduction of the Jal Jeevan Mission (JJM), the local administration, without assessing the actual need, began providing tap connections to every household. As a result, most villages now have two 24/7 tap connections per house, affecting the sustainability of these fragile sources.

The implementation of JJM has been marked by several shortcomings. The unregulated tapping of new water sources under JJM has disrupted the delicate balance of spring-fed ecosystems.

TAPPING OF SPRINGS AND STREAMS

New water sources were exploited without considering long-term sustainability or potential hydrological disruptions. Springs are naturally replenished through groundwater percolation and surface run-off. New water supply schemes diverted larger volumes of water from these sources to household pipelines, exceeding their natural recharge rates. As a result, some springs have started drying up or showing reduced discharge, especially during the dry season. Unlike traditional panyara-based systems, which relied on localized, sustainable withdrawals, the new infrastructure extracts water continuously, reducing stream flow. This has also affected downstream villages that previously depended on these streams for agriculture, livestock, and drinking water needs.

CLOUDBURSTS, FLOODS

Many villages have seen how JJM infrastructure gets severely damaged by cloudbursts and flash floods in recent years. Consequently, villagers have reverted to older connections. Water collection and pumping structures were placed without considering flood zones. Many intake points were destroyed by flash floods due to their proximity to vulnerable streambeds. This has led to repeated damage, requiring frequent repairs and fund allocations, making the system unsustainable both ecologically and financially.

WATER PRESSURE AND LEAKAGE

Due to the region’s topography, water pressure in the pipelines is excessive. The lack of control structures results in frequent leaks and overflowing tanks, a common sight in most JJM villages. Many villages now report small landslides and slope failures, possibly linked to constant water seepage from new infrastructure.

OVERUSE, WASTE

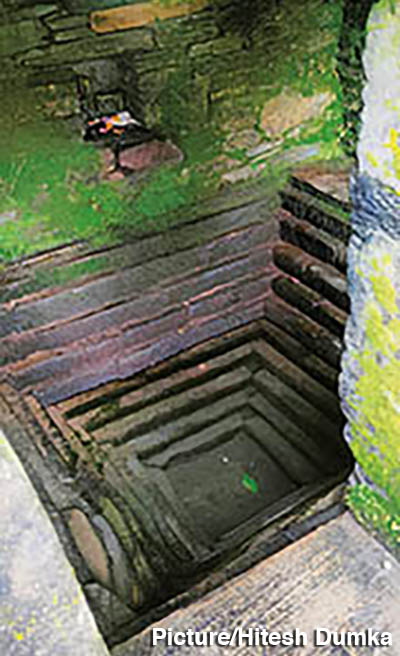

|

|

Stepwell in Dol village near Chopta in Uttarakhand |

raditionally, water was valued, conserved, and used efficiently, but the new system has led to behavioural changes that contribute to wasteful consumption, and mismanagement. Increased water availability has changed consumption patterns with potential to cause long-term water scarcity. Pristine water is now used excessively for flushing, kitchen gardening, bathing, washing, and cleaning, resulting in wasteful consumption patterns — which was not seen earlier. Dry toilets are being replaced with flush toilets. Frequent and prolonged bathing with multiple rounds of washing clothes and utensils are observed in such villages. Some households also began unnecessary cleaning of courtyards, streets, and vehicles. Earlier, villagers relied on panyaras and communal sources, requiring effort to fetch water. This encouraged conscious use and conservation. With water now available at the turn of a tap, the psychological association of scarcity and effort with water use has diminished. As a result, there is less caution in consumption, leading to higher and often unnecessary use.

WASTEWATER

There is no awareness or planning for wastewater disposal, resulting in polluted pathways and rising sanitation issues. Septic pit latrines combined with uncontrolled wastewater discharge further accelerates soil liquefaction, posing long-term geo-hazard risks. In traditional systems, water sources were collectively managed, with rules for fair use and maintenance. With individual household taps, water usage has become a private affair, reducing community accountability. No one feels responsible for ensuring sustainable use, and there are no village-level mechanisms to monitor wastage or think of community wastewater management. The unchecked increase in water usage, coupled with septic pit latrines, may be contributing to hill slope liquefaction, a matter that requires urgent study.

PRICE, REGULATION

Villagers were initially charged a one-time nominal fee, but rumours suggest a shift to a monthly billing system but without any clarity on consumption limits, supply schedules, or metering. No measures are in place to address leakages, misuse, and sanitation challenges. Villagers receive no training to handle basic maintenance issues.

UNEQUAL DISTRIBUTION

Allocation of contracts for JJM projects was influenced by political considerations rather than hydrological necessity. This meant that some contractors prioritized easily accessible locations instead of addressing hard-to-reach, water-scarce villages. Ironically, while many villages in Chauthan now have an overabundance of water, other villages in the state where natural water resources are scarce, still lack access to safe drinking water. JJM did not follow a need-based approach; instead, implementation was largely target-driven, aiming for numbers rather than equitable distribution. Water-deficient villages were not prioritized, even though they needed urgent interventions.

A spring-fed tank in a temple at Janki Chatti, en route to the Yamunotri shrine

A spring-fed tank in a temple at Janki Chatti, en route to the Yamunotri shrine

As a result, areas that already had self-sufficient traditional water systems got excessive infrastructure, while critical areas remain underserved.

The JJM scheme in this region appears to be target-driven rather than need-based, prioritizing numbers over sustainability, water quality, community participation, and sanitation. Contracts seem to have been awarded based on political considerations, with little regard for technical expertise. Consequently, key structures were installed in flood-prone zones, and were destroyed in subsequent floods, leading to a waste of public funds.

ALTERNATIVE APPROACH

Bhim Singh Rawat, researcher with the South Asia Network on Dams, Rivers and People (SANDRP), says that while ensuring access to piped water is important, the way JJM has been implemented in Chauthan Patti raises serious concerns. “A more holistic, decentralized approach, grounded in sustainability, local hydrology, and community involvement, is urgently needed to prevent long-term damage to water security in the region.”

He points out that no seasonal variability assessments were conducted before implementation. Springs and streams have natural fluctuations, with lower flows in the pre-monsoon months of March to May. The scheme operates as if water is abundant year-round, causing severe shortages during dry periods. Climate change has already increased extreme weather events, making springs even more vulnerable to depletion.

Addressing the decline of Himalayan springs is essential for ensuring water security and supporting the livelihoods of millions in the region. Can we revive these mountain springs? A scientific approach — including groundwater recharge studies, seasonal flow analysis, and community-based management — is essential to ensure that water security in the hills is maintained without degrading natural hydrology.

First of all, we need to develop a geo-database of all the springs in the Himalayan region. The information on their location and current status could be developed in the form of a Spring Registry at the village level. The information on local aquifers and springsheds could be overlaid on a map. It is also critical to understand spring hydrology. Integration of hydro-geological science and participatory community action can be designed around the springshed for their revival. Several villages are now designing contour trenches and percolation pits without any funding support through community participation. These actions will go a long way in reviving some of these lost springs, benefitting both the ecology and society.

If corrective measures are not taken, the long-term availability of water in the region will be at risk, leading to worsening shortages, environmental damage, and conflicts over water use.

Venkatesh Dutta is a Gomti River Waterkeeper and a professor of environmental sciences at Ambedkar University, Lucknow

Comments

Currently there are no Comments. Be first to write a comment!