The garden at the Savitribai Phule University merges with the woods

What is Pune losing and how fast?

Manjusha Ukidve & Ritu Gavandi, Pune

Pune was known as a green and picturesque urban paradise. It was a city people went to, to retire. Those days are long gone. The city is now a bustling industrial and manufacturing hub and home to the rapidly expanding IT industry with densities that match the economic opportunities it offers.

Rapid and ecologically insensitive development has led to the deterioration of the city’s natural heritage as tree-lined avenues have made way for flyovers and low-rise, low-density suburbs rich in greenery have morphed into neighbourhoods congested with high-rises.

The change has taken place over the past three decades. But what is worrisome is that the pace has quickened in recent years. The hurry to grow and accommodate more people has resulted in the city’s natural assets vanishing much faster now than they did earlier.

How can one keep track of this transformation? While it is easy to see what Pune is becoming, is it possible to have a record of what the city is losing? What were those green spaces and water bodies that simply disappeared? What is the condition of the local river?

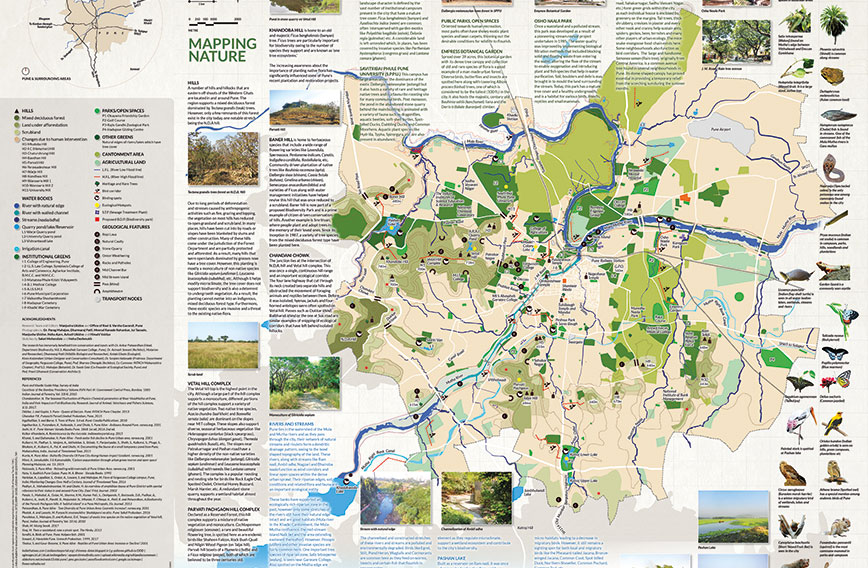

A green map of Pune brought out by the Landscape Foundation India, a non-profit private trust, seeks to do just this. The Pune map is part of a larger effort in 2017 when the foundation initiated a series of studies of historical Indian cities that explored their changing relationship with nature.

A green map of the city of Delhi in Hindi and English was adopted as a pilot project (see Civil Society, March 2018). It identified ecologically and culturally significant sites while pointing out the main environmental concerns.

The Pune map highlights changes in the natural environment of the city

The Pune map highlights changes in the natural environment of the city

The Pune map, in English and Marathi, similarly attempts to highlight the role and value of nature in the city and how it has evolved over the years. It aims to create awareness about the nature hotspots of the city from the past and the present in an effort to inspire residents to actively participate in their protection and conservation.

Pune has turned its back on its rivers that are now polluted due to domestic and industrial waste. The hills and lakes that were once safe from the city have now been engulfed by development. While it is nearly impossible to bring back the original natural landforms and water bodies that have been permanently altered by urbanisation over the years, it is possible to conserve the remaining natural hotspots of Pune by sensitising city residents and by demanding ecologically sensitive urban planning.

STORY SO FAR

Pune lies in the Maaval region of Maharashtra, the hilly transition zone between the Sahyadris (Western Ghats) and Desh (Deccan Plateau), at the confluence of the Mula and Mutha rivers. Strategically located on the trade route that connected the western coastal region and the plateau through a number of passes and ghats, the region has enjoyed a prominent place on the economic and cultural map of the Deccan since ancient times.

The early settlement of Punaka, the historical name of the city, was situated on the right bank of the Mutha, along its feeder streams. Ruled by different dynasties in succession, Punakavishaya was a region with small hamlets dependent on fishing and agriculture for sustenance that later combined to form a walled settlement known as Kasba Pune.

During the reign of the Peshwas in the 18th century, the city continued to grow and flourish on the Mutha’s right bank, connected to the undeveloped other bank by a sole bridge called the Lakdi Pul. The topography of Pune was majorly restructured during this time as existing nullahs were diverted and lakes created, freeing a large tract of land from the danger of flooding. An important feature of this era was the large-scale waterworks undertaken at Katraj where an underground system was constructed that supplied water to the city through a network of aqueducts, wells and tanks.

During the early colonial period the city crossed the two rivers and nullahs that had up till then defined its boundaries. Two cantonment areas were created by the British with a new landscape which had wide, tree-lined avenues and large open spaces, very different from the existing one. The natural green barriers of fields and farmland that lay between the old city and the cantonments were soon filled up by development. A number of bridges were built and development spread to the left bank of the Mutha. Dams were constructed over the river which became the chief source of water for the city and the earlier aqueduct system fell into a state of disrepair.

The later years of British rule and the post-Independence period saw rapid urbanisation and industrialisation leading to a loss of hinterlands and a change in the ecological character of the city and its surroundings. A number of large educational campuses were set up, which to date, add to the character of the urban landscape and gave the city its reputation of being the Oxford of the East.

A major event that left its mark on the city was the Panshet flood of 1961. Incessant rains caused the otherwise dry Mutha to flood, inundating both its banks and causing great damage to life and property. The river that had been an important part of the socio-cultural life of the city, supporting recreation, religious as well as cultural activities, now became the cause of much disruption and change. As a result of the flood, the city’s compact form was broken and it spread out rapidly, changing its relationship with the river forever.

Parvati Hill

Parvati Hill

SPLITTING HILLS

The hills are a prominent feature of the city’s landscape which originally supported a mixed deciduous forest dominated by Tectona grandis (teak) trees. However, only a few remnants of this forest exist in the city today. Due to long periods of deforestation and stress caused by anthropogenic activities, the vegetation on most of these hills has been reduced to open grassland and scrubland. Hills under the jurisdiction of the Forest Department are partially protected and afforested. However, mostly non-native species have been planted and the hills no longer support rich biodiversity. The Vetal and Parvati Pachgaon Hill complexes support both monoculture and diverse native vegetation and are a popular roosting and nesting site for birds like the rock eagle owl, spotted owlet, oriental honey buzzard and marsh harrier.

Baner Hill, to the west of the city, is home to a wide range of herbaceous flowering species. Community-driven plantation of native trees like Bauhinia racemosa, (apta) Dalbergia sissoo (shisam), Cassia fistula (bahava), Gmelina arborea (sivan), Semecarpus anacardium (bibba) and varieties of ficus along with water management initiatives have helped revive this land that had been reduced to a desolate scrubland. Once a continuous range and an important ecological corridor of the National Defence Academy (NDA), Baner Hill and Vetal Hill have now been separated by a four-lane highway. The hills that once contained the city within their boundaries have now been engulfed by development.

The banks of the Mula and Mutha rivers

The banks of the Mula and Mutha rivers

DEGRADED WATER SYSTEM

Pune lies in the watershed of the Mula and Mutha rivers. As the two rivers pass through the city, their network of natural streams and rivulets forms a dendritic drainage pattern, owing to the bowl-shaped topography of the land. These rivers, along with streams like the Ramnadi, Ambil odha, Nagzari and Bhairoba nullah, function as wind corridors and linear open spaces within the dense urban sprawl. Moreover, their riparian edges, soil conditions and related flora and fauna are important ecological entities. The banks of the Mula-Mutha supported an ecologically rich riparian zone in the past but today only some stretches of both rivers still have their natural edge intact.

Pashan Lake

Pashan Lake

The majority of Pune’s lakes are man-made reservoirs. Though few in number, they are an important natural element as they regulate micro climate, support a wetland ecosystem and contribute to the city’s biodiversity. But pollution through the source stream and other inlets has led to large-scale eutrophication and slow deterioration of these lakes over the years, destroying many micro-habitats and the population of migratory birds. Lakaki lake, once an abandoned stone quarry, is now a relatively good wetland ecosystem due to active conservation efforts by local residents.

OPEN SPACES

Man-made landscapes such as institutions, parks and cantonment areas collectively sequestrate carbon and reduce the heat island effect in the city. They sustain a variety of small living beings and support various food chains. Pune’s landscape character is defined by the vast number of institutional campuses present in the city that have a mature tree cover. Ficus benghalensis (banyan) and Azadirachta indica (neem) are common and often interspersed with garden exotics like Polyalthia longifolia (ashoka) and Delonix regia (gulmohar).

The Savitribai Phule Pune University campus is host to a variety of rare and heritage native trees and is a favourite roosting site for many birds. Empress Botanical Garden, an excellent example of a man-made urban forest, supports a dense tree canopy and a collection of old and rare flora.

Throughout the city, on local scale, bungalow neighbourhoods form green grids as each individual house is surrounded by tall trees and thick shrubbery on the margins. These grids function as green corridors and add to the natural wealth of the city.

In the past two decades, revival and restoration efforts like the stream at Osho Nala Park have attempted to convert wastelands into an urban green habitat for various birds, insects, reptiles and small mammals.

WAY FORWARD

Looking at the urban landscape today, one wonders about the future of the city’s natural wealth. Will Pune be able to retain its green

cover or will it perish with the ever-growing concrete jungle? If one were to go by the city’s citizen-led initiatives and intense activism to save its hills and rivers, one could be optimistic.

Community-driven plantation on hills with native trees, along with water management initiatives, have helped revive scrubland.

Successful initiatives like Lakaki lake have given hope. Once an abandoned stone quarry, this place is now a relatively good wetland ecosystem due to active conservation efforts by local residents. Restoration efforts like the stream at Osho Nala Park have attempted to convert wastelands into an urban green that is a habitat for various birds, insects, reptiles and small mammals. NGOs and the Municipal Corporation have initiated riverfront development projects that aim to reverse the harm caused to the river and restore its ecology along the banks. Efforts are also being made to create awareness amongst citizens about Pune’s rich natural heritage and these are paying off with more and more people joining the movement.

THE PROCESS

The research on Pune’s history started with references from literature available in both Marathi and English. We also collected archival photographs, sketches and maps that gave us a good base to begin our work on the map. Our talks with historians and architects, notably Avinash Sovani and Sharvey Dhongde, provided us a good idea of the city’s transformation over centuries. There were also a few old maps of the city but these were primarily made during the colonial period. It was a challenge for us to assimilate the textual references and the oral histories in the form of maps for the first section. Hand-drawn maps and sketches were created for the pre-colonial era, as well as the post-Independence period. Once these were made, a clear picture of the growth of the city and its natural features emerged. The maps helped us graphically establish a sequence of events that are important landmarks in the changing relationship between nature and the city.

Mapping Nature was equally challenging to compile. The Survey of India Map (2001) was the base on which we built our final map, adding details and including the changes that had occurred over the years (with the help of Google Earth Map). The objective was to represent the present condition of nature in the city — hills and rivers, natural and man-made water bodies, campuses, gardens and other open spaces. With the help of experts like Dr Nalawade, Dr Swati Gole, Ketaki Ghate, Dharmaraj Patil and Dr Ankur Patwardhan, various existing features, threats and potential opportunities for conservation were marked on the map. The research team made a number of exploratory field visits to observe and document the natural heritage of Pune through maps, sketches and photographs. These surveys helped us ground the information that we had acquired from literary sources and existing maps.

TIMELINES

It took us around three months, after initial discussions in March 2018, to do the background study, identify experts and collect base data like books, website references and base maps. This was followed by collaborative meetings with experts, identification of important aspects and establishing a clear methodology for further work. Extensive on-site survey and documentation led to the preparation of the first draft map that was again fine-tuned with inputs from experts. The final drawings in digital format started taking shape six months into the project and followed loosely the guidelines set by the Delhi map. Translation into Marathi took some time as the text had to be technically accurate, while being equally engaging and interesting to the lay person. The text, maps and illustrations were revised and fine-tuned by the team. It took us almost a year to present the map in the final format.

The funding of such research documentation projects is crucial, and we were lucky to get ready help from corporate houses who shared our concern for the city and its ecology. When research projects like these are supported by aware and sensitive citizens, it is the city that stands to gain. Apart from the money so generously donated for this cause, we are grateful to people who gave their time and expertise to the project. Their contribution is invaluable.

Landscape Foundation India is a non-profit trust founded by Geeta Wahi Dua and Brijender S. Dua. With a background in landscape architecture and architecture, they also conceptualise diverse landscape research works. They can be contacted at 011-41584375 and 9810600754. Email: [email protected]. Website: www.landscapefoundation.in

Comments

Currently there are no Comments. Be first to write a comment!