The hall at the Ant camp has been decongested

Ant carries its lockdown load in Assam areas

Civil Society News, Chirang/Gurugram

The lockdown to prevent the spread of the coronavirus comes with multiple challenges, but if you were a mental health patient in a remote village of Assam, what could you possibly do to find help?

Fortunately for a few thousand such patients, they have been able to turn to the Action Northeast Trust or Ant, the brilliant acronym it goes by.

Ant has been holding small camps for mental health patients in villages where it has been distributing medicines and providing medical advice. A big camp is held at the village of Rowmari in Chirang district, which is where Ant has its main office and a substantial campus.

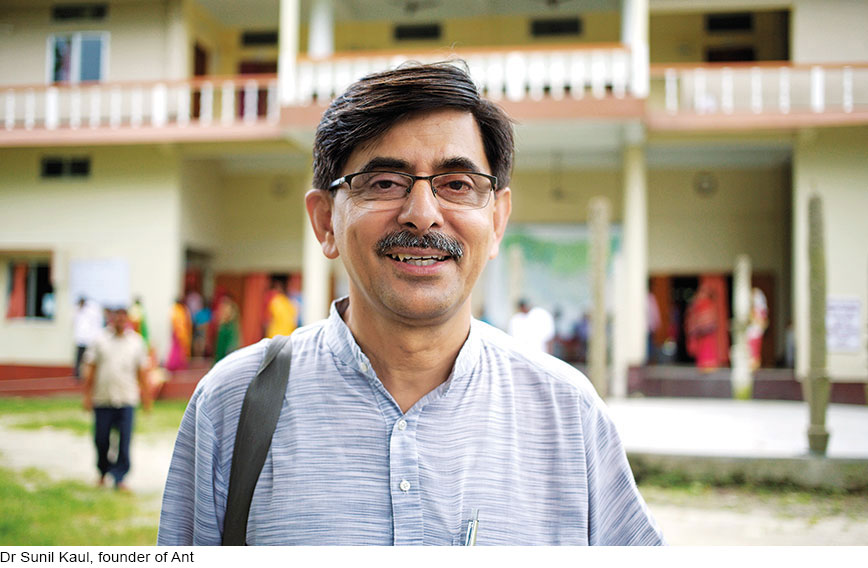

It is now 20 years since Ant was founded when Dr Sunil Kaul, a general physician, formerly in the Army, decided to dedicate himself to development of these remote tribal parts of Assam.

The NGO undertakes several projects, including providing livelihoods through a weaving centre that now very successfully markets its products under the brand name Aagor.

But the mental health initiative is special among all the things Ant does. It began some 10 years ago and is unique in that it takes psychiatric care to the doorstep of patients, making it both accessible and affordable.

The camp at the Ant campus is held once a month and is a big draw. People turn up from nearby districts and there could be as many as 600 patients arriving from early morning. The camps held in villages serve as extensions to this camp and are, of course, smaller with 80 to 90 patients.

However, these numbers represent just the tip of the problem. Much larger numbers are in need of professional attention and mostly don’t know how to make the trek to the urban centres in Assam and elsewhere in India for treatment. Ant meets a small part of this demand and is the only organization doing so.

Over time, Ant has developed a well-managed system for handling its patient load. But the lockdown has come with its own hurdles.

Immediately after the lockdown was declared, no camps could be held because all activity was prohibited. Dr Kaul was himself in quarantine for two weeks, having returned from Delhi, where he had stayed in his family home in Nizamuddin West.

Permissions from the district authorities weren’t easy to come by. Initial requests were stonewalled. But then three patients died — two due to epilepsy medication not reaching them on time and a third from suicide.

Citing these tragic deaths, Dr Kaul was able to convince district officials that mental patients needed regular supervision. Those on medication had to have their medicine stocks replenished. It wouldn’t do for the camps to be suddenly closed.

“I wrote to the Superintendent of Police and sent him pictures of how we were prepared for social distancing. I also told him that I would send him a WhatsApp message with our vehicle numbers and names of social workers every time they set out from our campus for villages,” recalls Dr Kaul , who is lean and hyper-energetic, and speaks so fast that it sometimes becomes essential to ask him to slow down.

Permission from the authorities followed his persistent efforts and the mental health camps were resumed. But there were other problems.

Nilesh Mohite, the psychiatrist who works with Ant, couldn’t make the journey from Tezpur because of the lockdown. So, he hasn’t been attending the camps though he is available for consultation on video.

Similarly, Dr Kaul, while still in quarantine when the camps started, would speak to patients and issue prescriptions too on WhatsApp. That was for a while and he was soon out.

It has been Dr Mintumoni Sarma who has largely held the fort. Dr Sarma is a general physician and he has been braving tough odds to come to the Ant campus from his home in Guwahati.

Ant’s mental health initiative follows a hub and spoke model. The campus is the base, which draws the largest number of patients. At the camp on April 24, around 350 patients turned up from all over neighbouring districts. In normal times, the number could be twice that. The village camps serve as extensions and are much smaller. They usually draw between 80 and 90 patients and these days the number is between 35 and 45.

Not every patient has to be examined by a doctor each time a camp is held. In fact, the majority just needs to replenish their medicines. A patient who needs a consultation is either one who is new or one who is registered but has a fresh complaint.

The Ant campus hall in which patients gather to pay to collect their medicines and meet the doctor is usually very crowded. To avoid a crowd now, a barrier has been created where patients who have only to collect their medicines are asked to show their prescriptions. The medicines are then brought and given to them. Circles have been drawn to ensure that patients and those accompanying them don’t stand too close to each other.

Ant charges patients just Rs. 300 per visit, which covers the cost of medicines and consultation. It is a piffling amount even in rural Assam. If a patient were to go instead to Tezpur or Guwahati, the big cities in the state, for treatment, the cost of travel and accommodation would be much more. Most patients need to be accompanied by relatives. Several days would be spent in going up and down.

Ant’s is a different approach to mental health care. First of all it recognizes that mental health problems are widespread and the numbers of patients are huge in a population as large as India’s.

These are also mostly patients with low income who remain underserved by qualified doctors. It is also unrealistic to expect them to visit psychiatrists for treatment. Many of them are unaware that they have mental health problems.

Ant has, therefore, reached out to them. It has created awareness among communities and spread the message that mental problems are treatable. It has also trained volunteers and social workers to administer medicines and counsel families.

Dr Mohite, who belongs to Maharashtra but has settled in Tezpur, says, “In the Indian context patients far outnumber psychiatrists. Innovations in approach are required. If the patient is doing well, a general physician is good enough to follow up on the patient. Motivating psychiatrists to treat people in rural areas is also important. A village-level camp can over time attract a psychiatrist from the nearest city.”

Dr Kaul began holding the camp at the Ant campus at the urging of another NGO. Soon that NGO backed out, but seeing the demand and not having the heart to turn people away, Dr Kaul kept the camp running.

Over time it has grown and become the only initiative of its kind. As concerns over mental health multiply, and awareness spreads, perhaps it will be seen as a model for others to take up and governments to promote.

When Civil Society visited the Ant campus to witness a camp, people turned up in a ceaseless stream from 5 am. They came on cycles, two-wheelers, auto-rickshaws.

Ant has neatly kept records of cases. It sources medicines and keeps three months of stocks, which have come in handy during the lockdown. In the villages where Ant reaches, patients have no other facility to turn to. It is particularly so amidst the fears of the coronavirus and the trauma of a relentless lockdown.

Ant’s work is a reminder that for healthcare to reach people it has to be friendly, accessible and affordable.

Comments

-

Amit Kumar Bose - June 25, 2020, 4:14 p.m.

An inspiring piece of news!