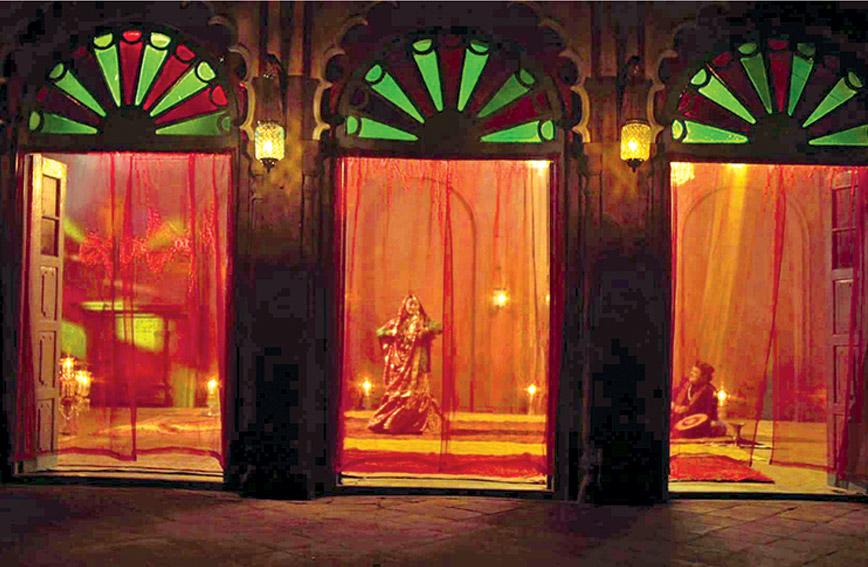

Each frame looks like a carefully orchestrated painting - with correct hues and spaces

The soul behind the song

Anita Anand

Begum Akhtar (1914-1974) was born in Faizabad in Lucknow, the daughter of a courtesan or tawaif. The tawaifs, women who catered to the nobility of India, particularly during the Mughal era. excelled in and contributed to music, dance (mujra), theatre and the Urdu literary tradition, and were considered authorities on etiquette. They were largely a North Indian institution central to Mughal court culture from the 16th century onwards and became even more prominent with the weakening of Mughal rule in the mid-18th century.

Starting her career as Akhtari Bai Faizabadi, she too was a tawaif. She married a lawyer, stopped singing publicly for about five years, and then emerged as a respectable Begum Akhtar.

The 64-minute documentary weaves through the times and tides of Begum Akhtar’s life — as a young girl, her initiation into music, her training under various gurus, her rise to stardom and eventually her death — as seen by people around her.

With carefully chosen black and white photographs and sound recordings from the All India Radio archives of her ghazals and interviews, Dandriyal takes us from the 1920s to the time of her death in 1974, through the neighbourhoods she grew up in, performed in and lived in. He overlays the appropriate ghazals over rippling waves, sunrises and sunsets, thundering skies with rain, gardens, and old trees and havelis — existent and reconstructed.

The original and the recreated come together in artistic and visually pleasing ways. For example, several clips, in colour, pan a bedroom with personal items and period furniture. In the background, a black and white TV shows Begum Akhtar singing. She is there, but not there.

The English subtitles are gracefully placed in various positions on the screen, so they can be read. Each frame looks like a carefully orchestrated painting — with correct hues and spaces that call out to the viewer. Watch me, they say. The exquisite visuals and the high-quality singing compete for attention from the eyes and ears.

There are charming vignettes throughout the film. For example, Begum Akhtar recorded for the Kolkata-based Megaphone Recording Company in the 1930s. Her ghazal, “Deewana banana ho toh deewane bana de,” was so popular that the company had to import another recording machine from England to meet the demand.

Dandriyal made the documentary for the Sangeet Natak Akademi’s celebration of Begum Akhtar’s birth centenary in 2014. How did he make the film he did?

“In my research, I kept in mind she was a big star and known all over India. Ghazals have survived largely due to her and what she brought to them. But there was limited visual material. There were some Doordarshan video recordings. It was creatively difficult, but challenging. In addition, there was not much documentation about tawaifs. I had to look for people who could speak about this. For, without the tawaif there is no Begum Akhtar,” says Dandriyal.

He wanted to focus on the emotionality of Begum Akhtar’s work.

“The more people I met, the more I heard about the pain or dard in her voice. And for the dard to work, I too must understand it, and get it across to the audience so they feel it too. Thus, I wove the story around the interviews and her songs. I tried to build the connection between that pain and the need to draw in the audience. I had to find people who knew her and her music on an emotional level and build the story,” explains Dandriyal, speaking about the process of putting the documentary together. The excellent camera work by Ranjan Palit brings to life the essence of what he tried to do.

“When a poet writes a ghazal it is theirs. When Begum Akhtar sings it, it is hers. And, when I make the film, it becomes mine. And mine is a visual medium. On the screen, it must be different. Otherwise, why would people come to see the film? Not just for the music, but for the visuals as well. That is what brings the music alive.”

The film does bring the music alive, in a monumental way. The documentary won the 2016 National Award for Best Biographical/Historical Reconstruction.

For further details on the film contact the director at

[email protected]