Koli Esru is about an impoverished woman striving to provide her daughter a taste of chicken curry

Kannada’s new films, young directors are going places

Saibal Chatterjee

Nationwide interest in Kannada cinema has never been higher. Thanks to the success of Kantara, the two chapters of KGF and 777 Charlie, there is renewed buzz around films from the southern state that hitherto lagged behind cinema in Tamil, Telugu and Malayalam in terms of reach and impact.

The spectacular numbers that KGF and Kantara registered at the box-office have dramatically altered the distribution-exhibition scenario for films from Karnataka. But with the mainstream biggies going all guns blazing, more personal films — happily, there is no dearth of them — are struggling to find takers. It is a crippling anomaly.

Karnataka’s most acclaimed filmmaker, Girish Kasaravalli, 73, has made only two films in the past 12 years or so, with his last work, Illiralare Allige Hogalaare (2020), not making it to the multiplexes. His previous film, Koormavatara, travelled to festivals across the world in 2011-12. He says: “There is no release outlet any more for my kind of cinema.”

The world, of course, continues to celebrate Kasaravalli’s seminal debut film, Ghatashraddha (1977), which was adapted from a novella by U.R. Ananthamurthy and remains a landmark in the annals of Indian cinema. The World Cinema Project of Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Foundation, George Lucas’ Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation and Shivendra Singh Dungarpur’s Mumbai-based Film Heritage Foundation have joined hands to restore the classic film in time for its 50th anniversary.

That apart, Kasaravalli’s legacy continues, directly and indirectly, in the work of a crop of young filmmakers trying to navigate a rapidly changing market. They soldier on, fully aware of how big the challenge of securing theatrical release for small films is. These films have been lauded at festivals and have received glowing notices from critics. The encomiums haven’t, however, translated into commensurate monetary returns.

The euphoria generated by Prithvi Konanur’s Pinki Elli and Hadinelentu, Natesh Hegde’s Pedro, Jaishankar Aryar’s Shivamma, Champa Shetty’s Koli Esru and Sumanth Bhat’s Mithya, each film a testimony to the potential of the directors, might tempt observers to conclude that independent Kannada cinema is in the midst of a creative efflorescence. It undeniably is but the filmmakers driving it are acutely aware of the hurdles that lie in their path.

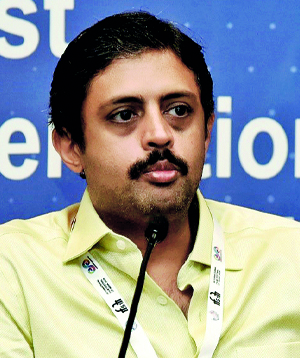

|

| Champa Shetty, director of Koli Esru |

Champa Shetty’s sophomore venture, Koli Esru (Chicken Curry), bagged the best film prize in the Indian Competition section at the Bengaluru International Film Festival (BIFF) in 2023. The actress and voice artiste-turned-filmmaker credits the festival with providing a platform to and celebrating independent filmmakers like her.

Her debut film, Ammachi Yemba Nenapu, made in 2018, in what is an exception rather than the rule, is streaming on Amazon Prime Video. Koli Esru is about a poverty-stricken mother who will go to any lengths to provide her 10-year-old daughter the taste of chicken curry.

Jaishankar Aryar’s debut film Shivamma won the New Currents Prize at the 2022 Busan International Film Festival. The software engineer-turned-filmmaker still retains his corporate job. For him to achieve the sort of financial security that would let him devote all his time to cinema, he would have to come up with a film for an audience wider than the one that Shivamma is likely to garner.

|

| Jaishankar Aryar, director of Shivamma |

“I made Shivamma,” says Jaishankar, “to satisfy my creative urges. I gave three years to the film — one year at the NFDC Film Bazaar, one for international festivals and one for Indian festivals. Since I wasn’t from a film background, I did not know better. But now I know that I cannot afford to spend three years on my next film.”

So, Jaishankar is “writing a film for a theatrical audience so that I can release it as soon as I am done”. That, he says, is how he would want his career to proceed — one film for himself followed by one for the audience. “I want to strike a balance,” he adds.

Shivamma, produced by Kantara writer-director-actor Rishab Shetty, is due for release in April. Natesh Hegde’s much-lauded Pedro, also produced by Rishab Shetty, premiered at Busan in 2021 and is now scheduled for theatrical release. “It is not easy for films that do not cater to the masses to find their way around in the domestic theatrical circuit,” says Hegde, whose next film, Vagachipani (Tiger’s Pond), is currently in post.

Produced by Rishab Shetty, who is himself working on a highly anticipated sequel to Kantara, Vagachipani is expected to surface at an international festival later this year.

A still from Pinki Elli

A still from Pinki Elli

|

| Prthivi Konanur, director of Pinky Elli |

“Getting an independent film off the ground may be easier today, but selling it is a huge challenge,” says Prithvi Konanur, director of Pinki Elli and Hadinelentu. He feels that predominantly market-driven filmmaking has distorted the ecosystem to such an extent that films that eschew popular ingredients run into a wall when it comes to distribution, be it in the theatres or on a streaming platform.

Talking about the release of Pinki Elli last year, Konanur minces no words: “It did very poorly…. People are not motivated enough to visit cinemas. They wait for the OTT release. But OTT platforms do not acquire a film unless it does a successful theatrical run.”

Critics may talk up their films and festivals might embrace them, but Karnataka’s independent filmmakers have to contend with apathy all around. “I don’t know what I’m going to make next,” says Konanur. “I have numerous scripts in my computer. But there are so many question marks to reckon with.”

|

| A still from Shivamma |

Significant rays of hope emanate from the growing number of self-taught filmmakers who aren’t backing off in the face of daunting odds. Utsav Gonwar has found support from multilingual movie actor Prakash Raj, who came on board as the presenter of his debut film Photo, released in Karnataka theatres on March 15.

With no marquee names and crowd-pleasing elements, Photo did not have people scrambling for tickets but it was another small Kannada film powered by honesty and authenticity. It returns to the dark days of the Covid-19 pandemic and its impact on migrant labourers as a fallout of the government’s knee-jerk reactions.

|

|

| A still from Mithya, a coming-of-age film |

The film centres on a 10-year-old village boy (from Raichur, the director’s hometown) who dreams of being photographed in front of the Vidhana Soudha. His mother sends him to Bengaluru with her husband, a construction worker. Father and son are stranded in the big city when the outbreak hits. They decide to make it back to their village by whatever means possible. It is a journey fraught with risk.

With unshowy and empathetic touches that pack a wallop, Photo highlights the tragedies that befell impoverished migrant labourers during the nationwide lockdown. It views the sorry spectacle through the eyes of a boy but unflinchingly drives home the inequalities that beset India.

|

| Sumanth Bhat, director of Mithya |

Another boy, 11 years old, is at the centre of Sumanth Bhat’s Mithya, a touching coming-of-age tale that plays out in the shadow of a tragedy. The film has been produced by Paramvah Pictures, a banner owned by actor-filmmaker Rakshit Shetty, who, with a few others, is spearheading a commercial resurgence of Kannada cinema while bankrolling independent films.

“Children,” says Bhat, an information technology man who owned and ran a design firm in his native Udupi before he became a filmmaker, “are extremely mature. Adults do not grasp how the mind of a child works, but children do understand what is going on around them.”

These young filmmakers are telling stories that matter, stories about real places and marginalized people. The trend merits our attention no matter how bleak the commercial prospects of these films might seem at the current juncture. It is a battle definitely worth fighting even though the current boom is not without its share of looming threats.

Comments

Currently there are no Comments. Be first to write a comment!