‘Ava’ is about a girl in Tehran at odds with her orthodox parents and school authorities

Toronto festival's stories of strife and salvation

Saibal Chatterjee, Toronto

Hollywood star Angelina Jolie had two films in the 2017 Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) — one as director, the other as executive producer. Both the titles stemmed from her active involvement with humanitarian work around the world. The first tells the story of a girl who survived the “killing fields” of Cambodia in the 1970s; the second, an animation film set in Taliban-ruled Afghanistan, journeys into the world of a pre-teen girl seeking freedom and happiness amid seismic changes.

First They Killed My Father, a Netflix production co-written and directed by Jolie, brings to the screen bestselling author and human rights activist Loung Ung’s memoir of the chilling Khmer Rouge years (1975-79) that began when she was five years old. The film depicts with skill and empathy the horrors of political violence and its brutal impact on innocent lives.

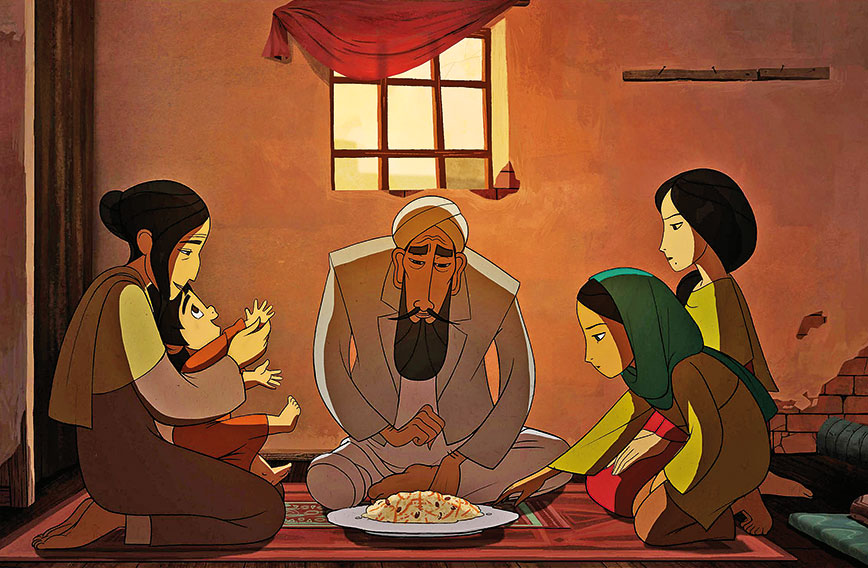

The Breadwinner, executive produced by Jolie, is Irish animation director Nora Twomey’s adaptation of Deborah Ellis’ award-winning novel. It revolves around an 11-year-old Afghan girl who disguises herself as a boy to earn a living for her mother and sister when her teacher-father is sent to jail by the Taliban. She draws strength from the love of her family and the regenerative power of storytelling.

Many an important film in the TIFF programme this year dealt with the repercussions of war, personal struggles for freedom and redemption, and tales of young rebels fighting to find their voices. “I believe that when we tell stories, we can heal,” says Vancouver-based Afghan-Canadian filmmaker Tarique Qayumi.

Qayumi’s second fiction feature, Black Kite, premiered in TIFF’s Special Presentations section. It represents an effort to use memory and imagination as a means to come to grips with Afghanistan’s tumultuous contemporary history. The film uses live action, documentary footage and animated passages to capture the tectonic political shifts that the war-ravaged nation has witnessed over the decades. It homes in on a kite-maker’s son who, in the company of his young daughter, clandestinely clings to his passion despite a Taliban ban on kite-flying.

“The film tells the story of a boy whose dreams are dominated by kites even as history stands in his way,” says Qayumi, who migrated to Canada from Kabul as an eight-year-old in the early 1980s. “Children of the post-Taliban period do not have a sense of history. This film is for them. I hope they embrace it,” says the director who also manned the camera in order to facilitate a guerrilla-style shoot aimed at evading unwanted Taliban attention and dodging suicide bombers.

'The Breadwinner' is about an Afghan girl who disguises herself as a boy

'The Breadwinner' is about an Afghan girl who disguises herself as a boy

After studying in the UCLA School of Theatre, Film and Television, Qayumi and his actress-wife Tajana Prka (also the producer of Black Kite) spent four years in Kabul working on docu-dramas for a progressive TV channel. “When the stint ended, we felt that we could not leave Afghanistan unless we told a story of our own. I had this idea in mind for some time. I wrote the screenplay in three weeks,” says Qayumi.

Qayumi’s wasn’t, of course, the only film in the Toronto programme by a director in exile exploring the current political and social realities of the land of his or her birth. Several other titles in the TIFF 2017 selection tackled the themes of political instability, displacement and rebellion against cultural and social conservatism.

Notable among these were Tehran-born Quebecois filmmaker Sadaf Foroughi’s Ava; second generation Pakistani-origin Norwegian director Iram Haq’s What Will People Say; and Zambian-British Rungano Nyoni’s I Am Not a Witch.

Foroughi, director of Ava, a fictional tale of a Tehran girl at odds with her orthodox parents and school authorities, was 20 years old when she left Iran for France, where she studied art and film and acquired a PhD in the philosophy of cinema. Maker of a string of acclaimed short films, she has lived in Montreal since 2009. “Ava is the story of my growing up years,” she says.

Getting her first feature film to the screen was no mean task for Foroughi. “I spent years looking for a producer. Nothing materialised, so I decided to produce the film myself,” says the 41-year-old director. Things are now beginning to look up: she has not only found an international distributor for Ava, she already has a producer on board for her next film.

The eponymous heroine of Ava is a creatively inclined girl who is prevented from meeting her best friend, playing the violin and dating. Her overprotective mother objects to her relationship with a boy and goes to the extent of taking Ava to a doctor for a pregnancy test — which is tantamount to an outrageous invasion of her privacy. Ava’s sympathetic father is powerless in the face of social expectations. The growing restrictions on the girl trigger acts of life-altering rebellion.

The female protagonist of Iram Haq’s deeply affecting What Will People Say, which has drawn inspiration from the director’s own life, finds herself in a similar situation in the Pakistani immigrant community in Norway. The film is the story of Nisha (played by 18-year-old Maria Mozhdah, a Pakistan-born girl raised in Norway) who runs afoul of her father (Indian actor Adil Hussain) when she is caught with her boyfriend in her bedroom.

Her father takes Nisha to Pakistan against her wishes and leaves her there with relatives to cut her off from the Western ways that he hates. “When I was 14 years old, I was kidnapped by my parents and forced to live for one-and-a-half years in Pakistan,” says the Norway-born Haq. “I have waited until I felt ready as a filmmaker and as a person to be able to tell this story in a wise and sensible way.”

The 41-year-old director debuted in 2013 with I Am Yours, about a Pakistani single mother in Norway struggling with her relationships with men and her equations with a traditionalist mother, which also premiered at TIFF and was the Nordic nation’s official nomination for the Oscars. “The heroine of I Am Yours is the woman that Nisha eventually became,” says Haq.

“I very often find inspiration from myself,” Haq told a media conference addressed by the 12 filmmakers who were competing for the Toronto Platform Prize at TIFF this year. “I like to deal with feelings of shame and what it triggers in us — loneliness, identity crises, and the feeling of being rejected and unloved.”

'First They Killed My Father' goes back to the chilling Khmer Rouge years

'First They Killed My Father' goes back to the chilling Khmer Rouge years

Lusaka-born Welsh filmmaker Rungano Nyoni goes from the strictly personal to the much larger canvas of societal and cultural practices in I Am Not a Witch, a film that garnered accolades earlier this year after its world premiere in the Cannes Directors’ Fortnight. Screened in TIFF’s Discovery, a section dedicated to upcoming filmmakers, the film is about a nine-year-old girl who is accused of being a witch and banished to a desert camp. She faces the prospect of either continuing to live this life or fleeing and risking being turned into a goat.

Nyoni, who was raised in Cardiff, researched for the film by spending a month in a witch camp in Ghana. She mixes straight-laced satire with broad surrealist touches to expose a reality of Zambia that borders on the bizarre. I Am Not a Witch is a debut film, but the self-assurance with which Nyoni has crafted it belies the director’s lack of experience.

The literal and the metaphoric flow into — and out — of each other in Nyoni’s treatment of the subject. She adopts a neutral stance on the theme of witchcraft but comes out without ambiguity against the plight of women and children who are branded and then horribly mistreated. I Am Not a Witch probes the injustice and violence that women are subjected to in tradition-bound Africa while investing the story with a universal resonance.

“The film sprang from several stories that I had heard about women in Lusaka,” Nyoni told the audience in a post-screening Q&A in Cannes in May. “I condensed all these anecdotes into one as they collectively epitomised what goes on in the witch camps.” Isn’t that true of all stories that heal and redeem, no matter where in the world they come from?