The coastal road will be built entirely on reclaimed land from the sea

Who really needs Mumbai's coastal road?

Derek Almeida, Panaji

A 29-km coastal road by reclaiming over 90 hectares of sea was being built at breakneck speed till an order of the Bombay High Court on July 16 brought it to a halt by asking for an environment impact assessment (EIA).

The road was being constructed by the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) in the face of objections raised by environmentalists and fisherfolk in Worli.

The coastal ecology with myriad creatures has had no say in the construction of this road although it would destroy their environment. Their only hope lies in green activists like Sarita Fernandes, associated with Vanashakti, one of six organisations who filed petitions in the Bombay High Court opposing the construction of the coastal road.

Fernandes is a Mumbai-based marine and coastal activist. She has a master’s degree in public policy from St Xavier’s College with specialisation in coastal policy.

In October-November last year, work on the south side of the highway began with large-scale reclamation which took residents and activists by surprise. “When work started on the south side we conducted a study and found that the small stretch near Worli had 36 species of intertidal marine life. That was when we got involved,” says Fernandes.

The coastal road is a 29.2-km project, of which the South phase will be built at a cost of Rs 1,316 crore per kilometre. The main rationale for the road is to increase interconnectivity from the suburbs to the south-end to decrease traffic congestion on existing public roads.

Several fishing communities will lose their source of livelihood once the road is constructed, but only 600 families from Worli have joined the fight to oppose the road and save their way of life.

“There is a misconception that the road will be built on stilts,” explains Fernandes, “but that is not the case. It will be built entirely on reclaimed land.”

Work on the project will be taken up in two phases. The stretch from the Princess Street flyover to the Bandra-Worli Sea Link (South) comprises the first phase while the second will go from Bandra to Kandivali. The eight-lane expressway was estimated to cost Rs 222 crore per km in 2011. Eight years later the cost has increased by seven times and those opposed to it say that the benefits are not clearly stated.

A 27-page report put together by Fernandes details several coastal violations and shows that the BMC had only one stakeholder in mind when planning the project — private vehicle owners, even though one lane on either side is expected to be reserved for bus transport.

According to the report, the road falls within Coastal Regulation Zone (CRZ) 1B, CRZ II, CRZ III and CRZ IV A, provisions enacted for protection of the coastal environment. One of the provisions in the environment clearance given by the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, states that project activity shall be carried out in accordance with provisions of CRZ notifications (2011) and shall render the coastal ecology of the area, including flora and fauna, to its original state after completion of the project.

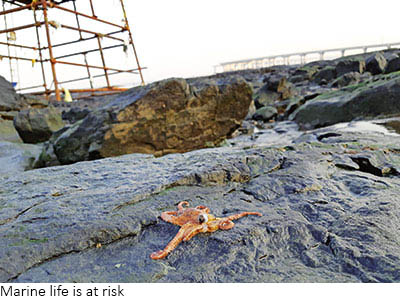

Coastal activists like Fernandes question how this is possible when the entire project is going to be built on reclaimed land. Her report claims that 340 marine inter-tidal species have been identified on the shores of Mumbai, all of which are under threat. “The intertidal environment, the zone between the high and low water, across the world supports a rich and unique biota consisting almost entirely of marine organisms," the report states.

At present a stay order has been issued by the Bombay High Court which recently finished hearing eight petitions, one of which was filed by Vanashakti, the NGO with which Fernandes is associated. “The crux of the matter is — can the road be constructed without reclamation and, second, is it really required,” says Fernandes.

Her report lists four grievances. First, no mitigation or action plan for environment protection has been made available since work started on the south side. Second, the report claims that out of 90 hectares of reclaimed land, 70 ha would be used to create green parks but no study has been undertaken on the marine life in the inter-tidal space which will be permanently destroyed. Third, no plan has been submitted for conservation of marine biodiversity. Fourth, there is a controversial study being conducted by the National Institute of Oceanography (NIO).

“The NIO study is void because it began after reclamation started and the coral and oyster beds in Haji Ali were already reclaimed,” says Fernandes.

Another issue is the large rock formations near Worli which date back to Mesozoic times and which are expected to be reclaimed for the road. The marine wildlife found in these rocky shores of Mumbai include Schedule I species like corals, sea cucumber and gorgonians under the Wildlife Protection Act 1972. The study states, “The mention of these species as an important and necessary stakeholder in all environment impact assessment reports and environment clearance given for the coastal road project, is zero to absent.”

Marine life is at risk

Surprisingly, the fishing communities at Versova, Juhu, Cuffe Parade and other areas have not joined the opposition to the project. The fishing settlement at Worli is the only one to take up cudgels against the road.

Members of the Worli community can be classified into three categories: First, fishermen fishing within the rocky shores without boats. Second, those using mechanised boats up to four nautical miles and then the fishermen fishing beyond four nautical miles.

“Once this road is constructed the intertidal space will disappear and all fishing communities dependent on it will lose their livelihood,” explained Fernandes. “The community at Worli is artisanal which means they are completely dependent on fishing in the intertidal zone. They were offered compensation, but rejected it on the basis of the inter-generational clause which ensures livelihood protection for future generations.”

The driving argument behind the project is ease of travel. According to the environment clearance, the road will reduce commuting time by 70 percent and fuel saving per day will be 34 percent.

Statistics show that in 1998 Greater Mumbai and Thane had 13.32 lakh three-wheelers, four-wheelers and more, and in 2017 this figure reached 65.26 lakh. Similarly, in 1998 there were 5.98 lakh two-wheelers which increased to 39.01 lakh in 2017. On an average, 700 new vehicles hit Mumbai roads every day.

However, Fernandes is not convinced. Her report states that the coastal road would benefit only 10.9 percent of the commuting population. “The metro project that aims at decongestion will alleviate pressure from BEST traffic. Local railways also contradict the need for a Rs 15,000-crore coastal road,” her report states.

According to the detailed project report (DPR), only cars are expected to be diverted along the coastal road, which means public funds are being spent to augment private travel. It further states that due to abutting land use and limited access to the facility, the growth rate (two percent) will be lower along this proposed road, while traffic along existing roads will grow at 5.5 percent per annum.

The DPR estimates that by 2043, traffic along existing routes will nearly double to approximately a lakh cars and nearly half of these will be diverted to the coastal road. Also, in order to move more traffic along the coastal route it is proposed to make it toll-free which goes against the user-must-pay principle.

However, not everyone buys this. For instance, the Bandra-Worli Sea Link is instructive in this regard. It was initially estimated to cost Rs 300 crore and handle 100,000 cars a day. It ended up costing Rs 1,600 crore and its average daily ridership stands at 32,312 cars.

Fernandes argues, “The figures and projections are vague and by building more roads, the government is encouraging use of private cars over public transport. Decongestion can only be achieved through public transport which needs to be strengthened. This coastal road is fancy, elitist and gross mismanagement of public funds.”