Bicycles distributed under the Sabooj Sathi scheme enable girls to get to school

Medinipur girls find a friend in Kanyashree

Subir Roy, Kolkata

Monika Soren, from Paschim Medinipur district of West Bengal, was born into the impoverished tribal Santhal community. Her father was the sole bread earner of her six-member family. As a little girl she would plant a stick into the ground, hang a basket from it, take her father’s bow and arrows and keep shooting at the basket.

When her father saw her determination, he ignored peer advice and sent her to school instead of arranging her marriage at adolescence. She first represented her school in shot put and then, when her teachers saw her obvious talent in archery, organised professional training for her from 2012. Eventually, she moved to the Sports Authority of India (SAI) facility in Kolkata for rigorous training under top professionals.

Over the past few years she has won many national awards. In 2015, at the age of 19, Monika was part of the national team that won an Asia Cup bronze medal in Bangkok. Her crowning glory till now has been being part of the national team that last year won gold at the Second Stage Asia Archery Cup Tournament in Taipei.

An important reason why Monika, who is still quite poor, is not already married and a mother is that she is a recipient of the West Bengal government scheme, Kanyashree Prakalpa, which offers poor girls financial incentives so that they keep going to school and do not get married too early.

The scheme seeks to improve infant and maternal mortality rates by preventing early marriage and resultant health risks and acts as a deterrent against trafficking. It is also a pushback against poverty which causes parents to get their daughters married as quickly as possible so as to have fewer mouths to feed.

The two-part scheme, launched in 2013, offers an annual scholarship of Rs 750 to school-going girls (Classes 8-12) in the 13-18 age group and a one-time grant of Rs 25,000 on reaching 18. Girls have to meet two conditions — not be married and come from a poor family with an annual income of less than Rs 1.2 lakh — and keep going to school regularly.

Over four million girls are enrolled under the Kanyashree scheme

Over four million girls are enrolled under the Kanyashree scheme

The most visible sign of the West Bengal government’s strategy is groups of girls going to school, neatly dressed and self-confident, on bicycles early morning in semi-urban and rural areas. The bicycles come from the scheme Sabooj Sathi, which seeks to distribute four million bicycles to children in Classes 9-12 to reduce dropouts. They have been distributed in the past two years, 2015-17. The bicycle is an enabler which helps the main programme, Kanyashree, succeed.

The big thing about the Kanyashree scheme is that it works, is visible across the state and in a few years has secured a space for itself in the popular imagination. Over four million girls are currently enrolled under it and nearly nine million have benefited from it till now.

In June, Kanyashree secured international recognition by winning the 2017 United Nations Public Service Award, becoming one of the three schemes across the world to be placed in Category I for “reaching the poorest and most vulnerable through inclusive service and participation”. Globally acclaimed for being comprehensive, efficiently implemented and easy to access, it has been adopted as a model for the central government’s Beti Bachao Beti Padhao scheme.

Kanyashree runs on information technology, both in doing things and monitoring the work done. It is delivered through a dedicated web-based portal (www.wbkanyashree.gov.in) which reduces paper work and response time. The system was developed in just two months in 2013 by the National Informatics Centre in West Bengal, taking in data on millions of girls, 17,000 institutions like schools, 13 government departments and 130 bank branches. UNESCO is a partner for the project and technically helps watch over it through a robust monitoring and evaluation process. The project began with a baseline survey so as to help evaluate progress over time.

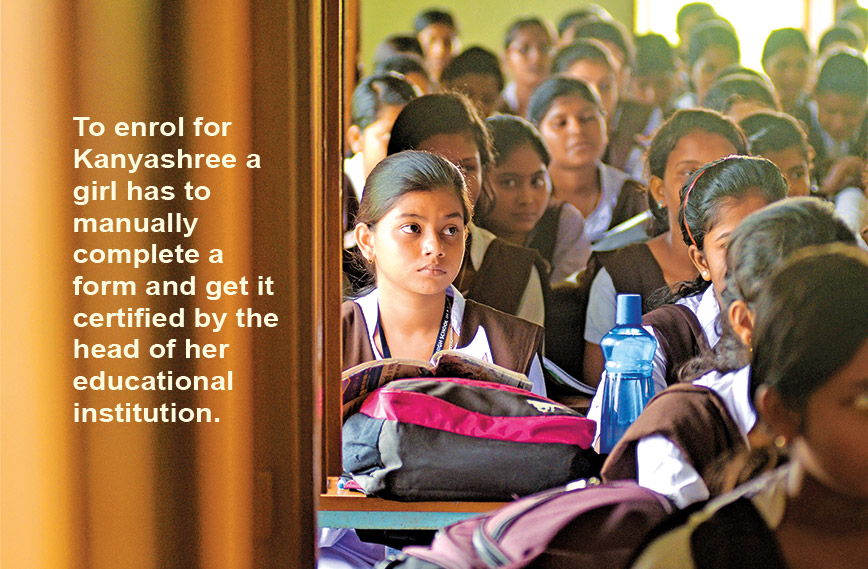

To enrol for Kanyashree a girl has to manually complete a form and get it certified by the head of her educational institution. When this form is presented at a bank branch it opens a ‘zero balance no-frills account’ and uploads the data. If the application is accepted, the amount is transferred to this account. All primary data on the scheme is entered by educational institutions.

“The fact that Kanyashree is a user-friendly programme has certainly helped,” Ersed Ali, teacher-in-charge at Howrah Unsani High School, is quoted as saying in a report, “Celebrating the Kanyashree Success” which bears the West Bengal government and UNESCO imprimatur. “The procedure for completing forms and registration is hassle-free. We have to update the school’s database on the portal weekly, but it is a task we are happy to do as it helps the students.”

How well has Kanyashree done on the ground? When Naureen Sultana, then 16, came back to her home in North 24-Parganas district from school one day, she found it decorated for some special do, only to learn that it was her engagement. Her impoverished father was an agricultural labourer. In protesting against this family decision, unbeknownst to her, she roped in the persuasive powers of her school teachers.

The big thing about the scheme is that it works

The big thing about the scheme is that it works

They were able to make her parents change their mind, partly by pointing to the financial gain from registering under Kanyashree. They also contributed an extra Rs 750 so that Naureen could buy a second-hand sewing machine. With vocational training made possible by Kanyashree, she was able to earn Rs 3,000 a month which she gave to her mother. This made her an asset instead of a liability for the family.

Pressure began to mount on Anima Mondal after she turned 13 to get married. She resisted the family’s plans, going to the extent of contacting the prospective groom to say that she already had a boyfriend! But by the time she reached Class 9 the pressure became unbearable as she was told by her family that by not marrying she was jeopardising the future of her younger siblings. When her family stopped paying her school fees she was able to continue with her studies by giving private tuition to younger children.

After thus ‘saving’ herself, Anima went on to play a leading role in a group called Khoj set up by the District Child Protection Society which trains young girls to become change agents by sensitising adolescents to the evils of child marriage, human trafficking and child abuse. Alongside, she trained to acquire the skills to get a job in the IT sector.

In line with this, Kanyashree Sanghas are coming up across the state. These are set up in consultation with the local authorities and offer school-going girls a safe platform where they can voice their concerns and raise issues affecting them. These forums give the girls courage to discuss their fears, insecurities and experiences of growing up in a society which is often unkind to them. They go beyond girls’ education to strengthen their life skills and access vocational training. Critically, the girls act as change agents — literally going door to door to convince parents about the need to send their daughters to school.

Once girls join the club they get to choose the skills they want to develop. Among the popular choices are making soft toys, paper flowers, tailoring, computer training, theatre and martial arts. Trainers are brought in from local self-help groups, health centres, Rotary Clubs and the police department. In spreading the messages about nutrition, hygiene, trafficking and early marriage, the Sanghas use devices like role play and street theatre.

These are still early days to get a quantitative measure of the success of the project but, says Manmeet Kaur Nanda, district magistrate of North 24-Parganas, “We have already met the targets for annual scholarships and one-time grants but it is not only numbers that make the Sanghas a success. There is a substantial change in the girls’ confidence. Today they and their parents ask me questions like, when can we expect to have another toilet in our school, or what does the future look like after Kanyashree? The Sanghas have played a significant role in instilling self-confidence in these girls.”

The Nadia district administration has gone a step further in preparing girls who are ready for the one-time grant for jobs. It has used a private agency, JIS College of Education, to take 32 of them through a four-month pilot training programme to prepare them for jobs in the business process outsourcing sector. A new world is opening up for Anita Das who can now use the computer, make internet searches and speak basic English. The cost of training, Rs 10,000 per head, is borne by the district administration. Says Sheela Singh Ghosh, a trainer, “Within four months we have seen remarkable change in them. They have become confident

and articulate.”

Kanyashree enables girls to complete school education. But what happens to them thereafter and to the still large numbers who fall through the net? In Coochbehar district which has few large urban centres, Kanyashree is working with Sabala, the government programme that puts out-of-school adolescent girls back into school and imparts livelihood skills.

In collaboration with Landesa, an international research and advocacy organisation, the district administration devised a training module to help Sabala girls build homesteading skills like running kitchen gardens and rearing poultry and goats. The training includes imparting entrepreneurial skills to enable the girls to run their own small businesses. On completion of the training, the girls are given seed capital by way of seeds and chicks by Sabala to get started.

Manjuri Sil almost got married. But government officials intervened and she went back to school. Then, with her one-time grant and Sabala training, she was able to financially help her parents. This has enabled her to take up graduate studies in college. Sabala helps a family see “value” in their girls. The Kanyashree-Sabala team identified some of the most vulnerable girls and put them through a four-day vocational training. The administration was “amazed to see how motivated the girls were” after receiving the training. “Leveraging the two complimentary programmes” was a “great learning experience”, pointing which way to go.

Comments

Currently there are no Comments. Be first to write a comment!