RAJIV KUMAR

Ever since his electoral victory, the question facing Prime Minister Narendra Modi has been: will he successfully lead India on an economic trajectory that will ensure rapid, inclusive and sustained growth in the coming years?

The stakes are unusually high. If the PM is successful, India can emerge as a good example of a pluralistic democracy breaking out of the low to middle-income trap. This will have global implications in economic and geo-strategic terms. Failure to push towards a higher economic trajectory and instead succumb to hubris, populist economic nostrums and to the premature ambitions of a global role would result in another unsuccessful economic take-off for India. This would be disastrous because a young, impatient and aspiring population is a double-edged sword. It can yield a hugely positive demographic dividend. But it can also precipitate social and political strife if its aspirations are thwarted and its potential goes unrealised.

Given this context, the Budget for 2015-16 was one of the most anticipated economic events in recent history. Two more contingent factors made it even more critical for this Budget to send the right signals.

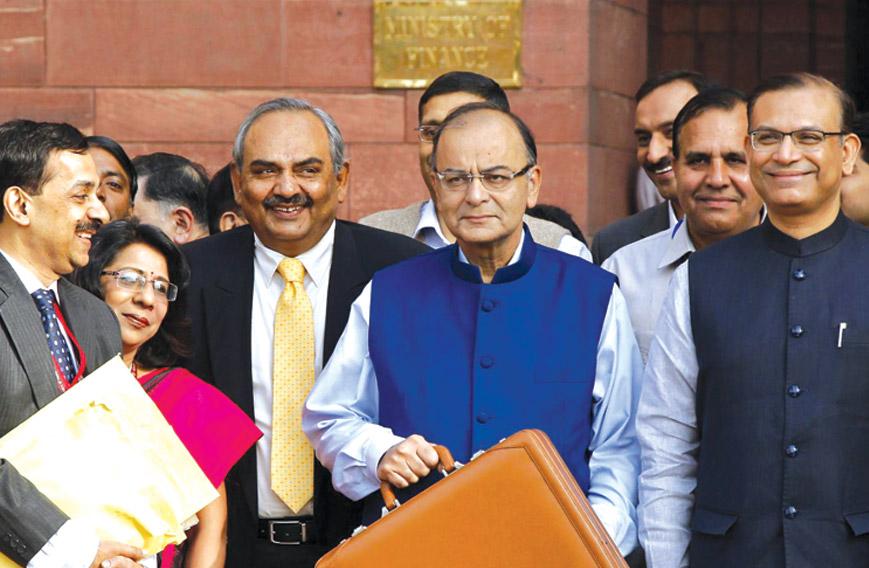

One, the investor community adopted a wait-and-watch stance. Second, there was a genuine fear that, with AAP’s handsome win in the Delhi elections in January on a populist platform, the PM and his Finance Minister, Arun Jaitley, could be under pressure to jettison the reform agenda and adopt a populist programme in the Budget.

They did not succumb to these pressures and have persisted with a policy of reigniting investment, accelerating growth and at the same time ensuring that the benefits of faster growth reach those at the bottom of the pyramid.

The Budget expectedly bears Modi’s imprint in mapping a path for putting India back on a rapid, sustained and inclusive growth trajectory.

There are seven principal components:

- Maintaining a stable macroeconomic environment by emphasising fiscal prudence and reining in inflation;

- Eliminating the three perennial deficits of infrastructure, governance and education, which afflict poor people the most;

- Improving the business environment for promoting both domestic and foreign investors to accelerate growth and generate employment.

- Dismantling the dysfunctional system of procedural clearances and permissions whose burden falls disproportionately on MSMEs;

- Plugging leakages in the distribution of subsidies by moving to a system of direct cash transfers;

- Affording greater fiscal autonomy to the states to enable them to design social sector programmes to suit their conditions; and

- Strengthening energy and food security while protecting the environment.

It is clear that the Modi-Jaitley team does not view the Budget as a one-off exercise to maximise short-term gains or achieve immediate goals. Instead, they have used it as part of a medium-term strategy to put the Indian economy on a higher and sustained growth path.

Overall, the Budget comes through as a pragmatic attempt, replete with small focused measures that will improve growth prospects. There is a conscious attempt to avoid a big bang or grab headlines. This is in keeping with the PM’s apparent preference for incrementalism combined with persistent follow-up to make a tangible difference on the ground. The approach does face the risk of being perceived as far too timid and full of bureaucratic inertia, and thereby unable to improve investor sentiment. This can be avoided by persistent follow-up for results on the ground.

The goal of generating 12 million jobs each year for the next two decades is a daunting but unavoidable target. Can the economic measures initiated by Modi’s government achieve such targets?

It depends on three factors. First, the PM’s ability to successfully build a political coalition in support of his economic agenda and to ensure necessary legislative sanction for some critically needed reforms. Second, the PM has to ensure that the bureaucracy has the capacity and necessary incentives to implement his economic reform. Third, external economic conditions must remain benign and India must retain the interest of foreign investors.

The PM’s best bet for putting together a supportive coalition lies in remaining focused on the development agenda and not allowing partisan issues to distract him. He will have to rein in his rightwing supporters from stoking communal issues and using anti-minority rhetoric. He has already stated that his government will not support any communal programme and will ensure that the benefits of growth are equitably distributed. It is possible that such a clear centrist and development-oriented stance in the pan-India context will yield rich dividends as it did in Gujarat.

It is perhaps even more important for the PM to ensure that his credibility as a pragmatic economic reformer is strengthened. He can achieve this by taking tangible steps to improve people’s daily lives and making conditions more conducive for ordinary businessmen. This will essentially require addressing the triple deficits in governance, infrastructure and education.

Substantial progress in these three areas can be achieved through executive action, without having to face legislative hurdles. These include: measurable and visible reduction in corruption; easier entry and exit conditions for businesses; freeing MSMEs from the deadening hand of petty bureaucracy and rent-seekers; and achieving greater efficiency in the delivery of public services, especially primary education and basic health. Substantial progress in these areas will ensure that Modi’s political credibility continues to rise, making it more difficult for opposition parties to unify against his reform agenda. It will also help him thwart pressures from his rightwing supporters.

It is not entirely clear that the required executive capacity is available. The PM has to create the required capacity in his Cabinet and senior bureaucracy to effectively address the three critical deficits. He will also have to re-engineer the incentive structures for both the political leadership and senior bureaucracy to deliver or be held accountable for desired outcomes in addressing the three deficits. Modi has a reputation for successfully exploiting the inherent potential of an operating system. Let’s hope that this will allow him to get the best from the bureaucratic establishment that he has inherited, but which he himself described as largely broken during his Independence Day address.

He would, therefore, do well to augment this capacity by freely borrowing talent from the private sector and civil society. This is especially true for designing new policies and coming up with new solutions where sheer incrementalism may not suffice. The PM will have to drive the bureaucracy to higher levels of efficiency, transparency and accountability and be prepared to augment it where necessary.

Rajiv Kumar is Senior Fellow, Centre for Policy Research, and Founder-Director, Pahle India Foundation.

Comments

Currently there are no Comments. Be first to write a comment!