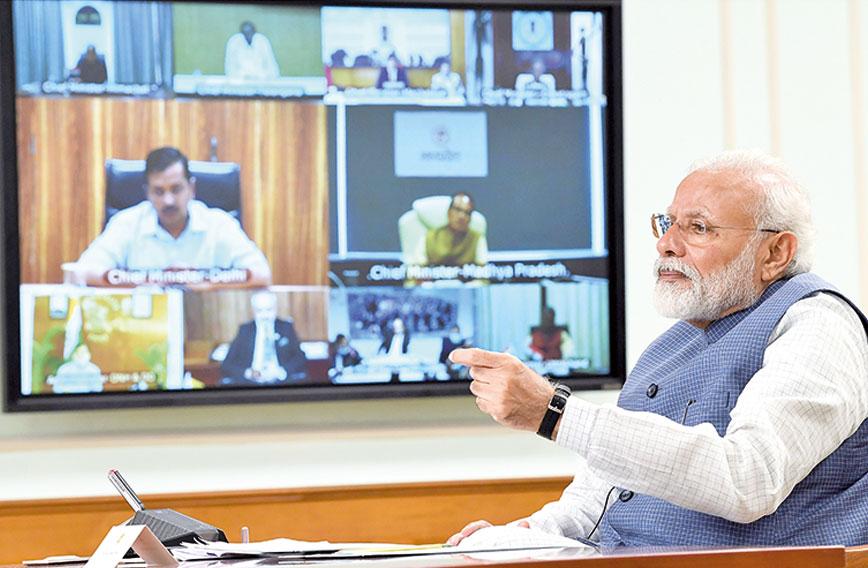

The Prime Minister has had no real contact with Chief Ministers. The first videoconference with them was three weeks after the lockdown

Strong centre and the politics of federalism

Sanjaya Baru

The Centre is a conceptual myth! So declared film-actor-turned-political leader N.T. Rama Rao, founder of the Telugu Desam Party and the first non-Congress chief minister of Andhra Pradesh. He joined hands with such powerful provincial leaders as Jyoti Basu in West Bengal, H.N. Bahuguna in Uttar Pradesh, Sharad Pawar in Maharashtra, Farooq Abdullah in Jammu & Kashmir and Devi Lal in Haryana to demand more power – fiscal and administrative — for states and non-interference by the Centre in areas that were constitutional responsibilities of state governments. In office in West Bengal and Kerala, the Left Front joined NTR and other non-Congress state governments to mount a major campaign in the early 1980s for more equitable Centre-state financial relations. West Bengal Finance Minister Ashok Mitra, a distinguished Left economist, led the charge, convening a national conference on Centre-state relations in Kolkata, and many non-Left economists of repute, like fiscal policy expert I.S. Gulati, joined that campaign.

Not only was that alliance of state leaders a powerful one, but the Centre was at the time in the charge of a chastened Indira Gandhi. Defeated in the post-Emergency elections of 1977 for running what was by then the most centralized administration since Independence, Indira Gandhi returned to power in 1980 saddled with a weak economy and problems of various kinds. In a conciliatory mood, she appointed the Justice Sarkaria Commission on Centre-State Relations in 1983. That was the first attempt after Independence at a review of Centre-state relations.

While the Constitution describes India as a “Union of States”, its principal architect, B.R. Ambedkar, described the arrangement as “unitary in extraordinary times” but “federal in ordinary times”. War was mentioned as one such ‘extraordinary’ situation when the Centre can assume a variety of powers at the expense of the state. There is also a constitutional provision for the declaration of a ‘financial emergency’. The Sarkaria Commission made several recommendations aimed at reversing an incipient trend towards centralization, introduced mainly during Indira Gandhi’s Emergency regime. Though, to be sure, the first time constitutional provisions were misused by the Centre to dismiss an elected state government was when Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru dismissed the government of communist leader E.M.S. Namboodiripad in Kerala in 1957.

BALANCE OF POLITICAL POWER

While the Constitution defines India’s federal/unitary governance structure, in practice the balance of power between the Centre and the states has been shaped more by politics than by the Constitution. Thus, in the 1950s Nehru was the all-powerful PM in Delhi but he had to deal with a number of politically powerful CMs in states and so an equilibrium of sorts prevailed at the time. The 1960s, on the other hand, was a decade in which India had relatively weak PMs (Nehru in his last years followed by an uncertain Lal Bahadur Shastri and an Indira Gandhi in her “goongi gudiya” (dumb doll), pre-Bangladesh war phase). The Sixties was a decade of powerful CMs — EMS in Kerala, Atulya Ghosh in West Bengal, K. Brahmananda Reddy in Andhra Pradesh, C.N. Annadurai in Tamil Nadu, Mohanlal Sukhadia in Rajasthan, Kamalapati Tripathi in Uttar Pradesh and so on.

The pendulum swung the other way in the 1970s, with Indira Gandhi emerging the all-powerful PM and appointing puppet CMs in Congress-ruled states and dismissing governments of non-Congress CMs. The 1980s then saw the rise of non-Congress ‘regional’ parties and provincial leaders and, despite having over 400 MPs, Rajiv Gandhi found his writ did not run easily across the country. Interestingly, the period from 1989 to 2004 saw a balanced equation emerge between the Centre and the states with Prime Minister P.V. Narasimha Rao and Atal Behari Vajpayee functioning as consensual leaders, given their narrow parliamentary majorities, and the PMs of four short-lived coalitions — V.P. Singh, Chandra Shekhar, H.D. Deve Gowda and I.K. Gujral — depending on several CMs for their own survival in office.

Prime Minister Manmohan Singh’s decade in office was defined by a paradox as far as Centre-state relations are concerned. On the one hand, being a minority government in alliance with a powerful Left Front, the Singh government in Delhi had to be mindful of the sensitivities of state governments and regional parties. On the other hand, given the enormous increase in central government spending in areas which are the responsibility of state governments — education, health, urban development, social welfare, rural roads and so on — the Centre exerted enormous influence on the functioning of state governments. Programmes like the National Rural Health Mission and the National Urban Renewal Mission had incentive systems that sought to influence state government policy by linking it to financial allocations.

While the so-called ‘era of coalitions’, 1989-2014, saw a more balanced political equation emerge between the Centre and the states, the expansion of central funding in areas that are the responsibility of states through ‘centrally-sponsored schemes’, increased the Centre’s fiscal clout over states.

COOPERATIVE FEDERALISM

As chief minister of Gujarat, Narendra Modi identified himself with the view that the centralization of funding through centrally-sponsored schemes went against the federal spirit of the Constitution. He found it demeaning that as an elected political leader and head of a state government he had to lobby with unelected, non-political professionals at the Planning Commission to get the funding he needed for projects that were his government’s priorities. It was this experience that encouraged him to promise that as prime minister he would adopt “cooperative federalism”

as his mantra. This was widely welcomed by advocates of fiscal federalism who imagined that as a former chief minister he would be more sensitive to the interests of the states in his new avatar as prime minister.

However, in practice Modi has been no different from other powerful PMs and he is now being accused by most non-BJP CMs of running an excessively centralized regime. In his most recent newspaper interview (Economic Times, October 29, 2020) Modi defended his record as PM, stating, “The last six years have seen the spirit of competitive and cooperative federalism in all our actions. A country as large as ours cannot develop only on the one pillar of the centre, it needs the second pillar of the states.” He went on to claim that in dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic, “Decisions were taken collectively. I had videoconferences with CMs multiple times to hear their suggestions and inputs, which has no parallel in history.”

Apart from the fact that Modi’s first video-conference with CMs was on April 10, 2020, three weeks after the first lockdown decision was unilaterally imposed on the entire country, the truth is that there were no regular consultations with CMs through his entire first term in office. Modi is the first PM to have dispensed with the institution of the National Development Council, a gathering of central ministers and chief ministers that has been an important institution of cooperative federalism. Modi’s critics say that the PM initially tried to play the national hero, unilaterally imposing a nationwide lockdown with four hours’ notice and urging all citizens to clap hands and light lamps, and only when he realized the pandemic and the lockdown could prove politically counter-productive did he begin involving the states and placing the burden of managing the consequences on them.

THE FISCAL DIMENSION

At the heart of Centre-state relations lies the problem of finance. In recognition of this the Constitution provided for the appointment of a Finance Commission once every five years to examine and recommend principles for the “distribution of the net proceeds of taxes between the Union and States and also the allocation of the same among the States themselves”. The Finance Commission is also expected to examine and define from time to time the devolution of revenues and financial relations between the Centre and the states. Interestingly, till 1998 all the Finance Commission chairpersons were politicians and some, like Y.B. Chavan and K. Brahmananda Reddy, had even served as chief ministers and were known to be strong advocates of greater devolution of finances to states. From 1998, however, the central government began naming professional economists and bureaucrats, with a record of serving the central government, as chairpersons.

Successive Finance Commissions have helped increase the states’ share in centrally collected taxes that become part of the divisible pool. The shift to a Goods and Services Tax (GST) was also managed well with the Centre taking the states along with it. At the parliamentary event at which GST was officially launched the then finance minister, Arun Jaitley, paid handsome tribute to four state finance ministers for their cooperation in enabling a national consensus on the GST scheme adopted. The four were West Bengal’s Amit Mitra (TMC), Kerala’s Thomas Isaac (CPI-M), Bihar’s Sushil Modi (BJP) and Jammu & Kashmir’s Haseeb Drabu (PDP).This was, in many ways, the high point of ‘cooperative federalism’ in Modi’s regime.

In his second term and faced with the economic and fiscal challenges posed by the post-COVID lockdown, Modi has been less sensitive to the needs of state governments. It took considerable protests on the part of state governments and the coming together of non-BJP governments for the Centre to relent on the issue of helping states bridge the revenue gap due to the negative impact of the lockdown on economic growth and the consequent loss of revenues.

The Fifteenth Finance Commission has been tasked by the central government with exploring ways in which the Centre can fund its rising defence budget. It remains to be seen how the commission will address this. There is every possibility that it would recommend increasing the Centre’s share of the divisible pool. Given the nationalist mood of the ruling BJP, it can easily generate support for this. However, the real reason the Centre is unable to fund the activities it is required to under the Constitution, like national defence, is because it has been increasing its funding of activities that ought to be in the realm of state governments. This has happened for half a century, since prime ministers like to be remembered by what they do at the community level. Thus, centrally-sponsored programmes in areas such as health, rural roads, education and social welfare have been named after successive PMs. Unless there is a more rational reallocation of spending priorities between the Centre and the states, the central government will find it difficult to find funds for defence and national security, which are about the only things that the Centre is required to do. For the rest, the responsibility remains with the states. That is precisely why NTR said the Centre was a conceptual myth. But politics has inverted the equation.

Going forward, the BJP will have to come to terms with India’s essentially federal character and not view this as a weakness. Rather, India’s strength lies in the concept of ‘unity in diversity’. Thus, allowing greater fiscal and administrative autonomy to states need not be viewed as weakening the nation. It ought to be viewed as strengthening the bonds of unity. In converting Jammu & Kashmir from a state, that was demanding greater autonomy, to a Union Territory directly administered by New Delhi, the Modi government has taken a step away from the spirit of the Constitution. Restoring statehood to J&K and granting greater administrative autonomy can only strengthen the bond with the state.

This principle holds true for the rest of the country. China, Canada and the United States offer good examples of strong provincial governments. New Delhi has to show sensitivity to the individual personality of states, especially of those that are on the nation’s physical periphery like the Northeastern states, Tamil Nadu, Kerala, J&K and the island territories, and desist from imposing the BJP’s monochromatic “Hindu-Hindi-Hindustan” view of this multi-lingual, multi-cultural, multi-ethnic republican democracy of ours.

Sanjaya Baru is a writer and Distinguished Fellow at the Institute for Defence Studies & Analyses in New Delhi.

Comments

Currently there are no Comments. Be first to write a comment!