Nandita Bhatt

'Me too' help for domestic workers

Sidika Sehgal, New Delhi

In November 2016, when the Martha Farrell Foundation (MFF), a non-profit, began working with domestic workers in Delhi and Gurugram to address sexual harassment, they found the women reluctant to speak about their experiences. It was only after building trust that they began to talk. The breaking point came in 2018 when the women told MFF activists that a 17-year-old girl in Gurugram had committed suicide because her employer had sexually abused her.

Most domestic workers are the only earning members of their family. Losing an income is not an option. Since they are migrants in a city far from home, they feel even more vulnerable. Thus they either see sexual harassment as a routine work hazard or they ignore it. Taking action is almost never an option.

But the Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace Act, 2013, mandates that a Local Committee (LC) in every district should be set up to which domestic workers can complain. The Act recognises the right of domestic workers to a safe workplace, and homes as a workplace for domestic workers. The Local Committee is meant to be under the jurisdiction of the district magistrate (DM) or district collector (DC).

Through RTI enquiries filed between September 2016 and March 2017, MFF found official data on Local Committees. Out of 655 districts in India, only 29 percent replied that they had formed a Local Committee. There was no functioning Local Committee in Delhi at that time. Two existed but only in name.

When MFF presented the data in September 2018 to Delhi’s deputy chief minister, Manish Sisodia, he instructed all DMs to form Local Committees by November 2018.

Earlier in June 2018 when MFF activists did a rapid survey with 291 domestic workers in Gurugram and Delhi, they found that they did not know anything about Local Committees.

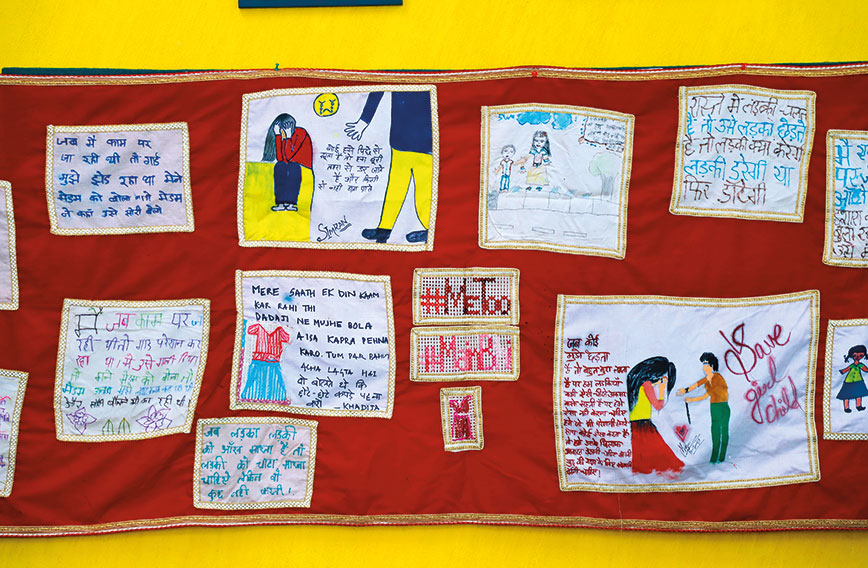

Drawings by domestic workers describe the harassment they face

Drawings by domestic workers describe the harassment they face

Even if they did, it would have taken them time to reach the Local Committee’s office and that meant missing work. Nandita Pradhan Bhatt, director of operations at MFF, says, “It is the Local Committee’s job to go looking for women, not for the women to spend a lot of money to come looking for the Local Committee. Every last mile, each woman must be aware of the issue and that she can complain and where.”

Bhatt is a member of southeast Delhi’s Local Committee and she has been able to bring about some change. The district officer of the Department of Women and Child Development (DWCD) is also a member of the Local Committee. She mentioned that she has a cadre of anganwadi workers and supervisors under her. She suggested that this workforce could be harnessed to reach domestic workers.

“Anganwadi workers who look after the children of domestic workers, share a rapport. As peers, they can strike up conversations about sexual harassment and tell them about the redressal mechanism available for them,” says Bhatt.

Bharti Sharma was chairperson of the Local Committee in southeast Delhi district when this model was adopted. She said that they were conscious about not increasing the burden of the anganwadi worker. “There is a lot that can be done through conversation,” she remarked.

The role of the anganwadi worker is to encourage the domestic worker to report and to facilitate writing the complaint if required. In the pilot model developed by MFF, the anganwadi worker passes on the written complaint to the Child Development Project Officer (CDPO), who sends it to the district officer of the DWCD. This postal chain allows the domestic worker to file a complaint without missing work.

MFF held a training session for the CDPOs and supervisors and a training session for the anganwadi workers of southeast Delhi district. Bhatt, who conducted the training session, told them about the Act, their responsibilities and what the Local Committee is. The officers felt that an awareness campaign was not difficult to implement.

Sharma’s tenure as chairperson ended in July 2019. Between November 2018 and July 2019, the Local Committee examined seven to eight complaints. During the inquiry, both the complainant and the accused testify, present documents for evidence and furnish witnesses, if any. The Local Committee submits its final report to the DM who adjudicates. The Local Committee is only a recommending body. It has no power to initiate criminal proceedings. It is up to the DM to forward the complaint to the police.

Only one complainant was from the unorganised sector. The rest were women who worked in the organised sector. They were either dissatisfied with the decision of the ICC (Internal Complaints Committee) or worked in a company that didn’t have an ICC. Sharma was disappointed that they hadn’t impacted the unorganised sector.

Sharma says that domestic workers need to be empowered and encouraged to complain. “There is still a long way to go. Let’s try this model out. It might fail. But unless you try, how are you going to find out?” One training session is obviously not enough.

The 2013 Act sanctions no budget for the Local Committee. In southeast Delhi district, getting a room to sit in and a cupboard to store documents was a challenge. Bhatt explained that MFF could have held the meeting on their premises, but a constitutionally mandated body like the Local Committee is the government’s responsibility.

Sharma also suggested that putting up posters about sexual harassment outside anganwadis could help. They would help spark a conversation. But the lack of a budget stood in the way of implementation. Neither the DM nor the DWCD have a budget for this.

District magistrates are not always aware of their responsibility towards the Local Committee. There is also no continuity. In southeast Delhi, the DM has changed every two months. “We shouldn’t have to ask the DM to be cooperative. It should be a given,” Sharma asserts.

Employers, on the other hand, are aware of the rights of their domestic workers. After all, many employers work in the organised sector and understand the concept of workplace sexual harassment. “We are very bad employers. We do not take care of those who work for us,” Sharma says.

Both Bhatt and Sharma argue that sexual harassment should be a labour issue, not only a gender one. Domestic workers are not included in any labour laws. Their work is not recognised as labour, even though it allows people in the organised sector to work. Also, the sexual harassment law needs to be made gender neutral and include LGBTQIA and men.

During Sharma’s tenure, the six-member committee comprised two men and four women. This was a conscious decision because she believes that both the complainant and the accused should feel comfortable when they tell their story. The feeling is that if there is no man on the committee, men won’t get a fair trial.

According to Bhatt, the next step is to share their research with organisations that are working with domestic workers. A meeting of all Local Committees in Delhi to discuss what they have learnt and the challenges they have faced is also on the agenda.

Comments

-

Evita fernandez - June 9, 2023, 4:14 p.m.

Yes female domestic workers are subject to a variety of challenges. I support the domestic workers movement and it should become a national force to reckon with for us who are privileged to employ domestic workers. I firmly believe we need to treat them with respect, kindness and also ensure they are covered with medical insurance. Some of us can go a step further and begin an account similar to a provident fund which the domestic worker can use later. The laws for this vital “tribe” must be strictly enforced with the hope they are protected from sexual abuse by their employers or by other male members of the family.