JAGDEEP CHHOKAR

The phrase ‘criminalisation of politics’ entered the Indian lexicon in 1993 when it was used by the Vohra Committee which had been set up “to take stock of all available information about the activities of crime syndicates/mafia organisations which had developed links with and were being protected by government functionaries and political personalities”.

This high-powered committee stated unambiguously that there was a “nexus between criminal gangs … and politicians … in various parts of the country...” and that there were “underworld politicians”.

Responding to a public interest litigation (PIL) by a civil society organisation, the Supreme Court ordered that every person contesting an election to the parliament or an assembly would have to disclose all criminal cases against him/her in a sworn affidavit, as a necessary part of the nomination form.

Data from these affidavits over the years resulted in what were then felt to be startling revelations. Out of 543 MPs of the Lok Sabha in 2004, as many as 128 (24 percent) had criminal cases pending against them. This number increased, and continues to increase, to 162 (30 percent) in 2009, 185 (34 percent) in 2014, and 233 (43 percent) in 2019.

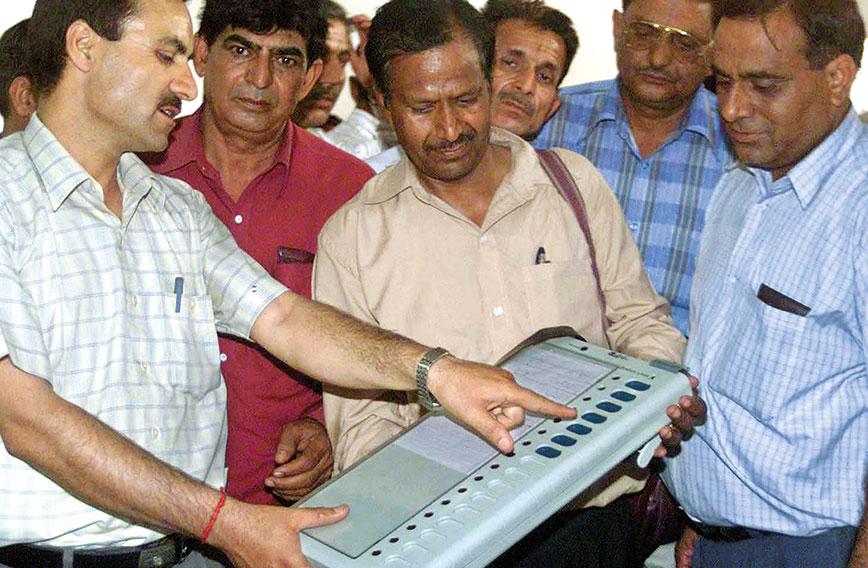

In 2004, the People’s Union for Civil Liberties (PUCL) filed a PIL in the Supreme Court asking for a new button to be provided on the electronic voting machines (EVMs) called NOTA (None Of The Above). The primary purpose was to protect the confidentiality of a voter who wanted to cast his/her vote but did not want to vote for any of the candidates. The existing provision in 2004 was that such a voter would have to sign on a form saying s/he did not wish to vote for any of the candidates. Since these forms were preserved, the identity of the voter could be found out which created the possibility of some of the candidates harassing that voter because s/he did not vote for one of them. Secrecy or confidentiality of one’s vote so that one can vote without any fear of consequences is, in any case, an accepted principle of democracy all over the world.

The Supreme Court in a judgment delivered on September 23, 2013, directed the Election Commission to “provide necessary provision in the ballot papers/EVMs and another button called ‘None of the Above’ (NOTA) may be provided in EVMs so that the voters, who come to the polling booth and decide not to vote for any of the candidates in the fray, are able to exercise their right not to vote while maintaining their right of secrecy”.

The court made very significant observations in the judgment, one of which said, “When the political parties realize that a large number of people are expressing their disapproval with the candidates being put up by them, gradually there will be a systemic change and the political parties will be forced to accept the will of the people and field candidates who are known for their integrity.”

This was important because it had become clear over the years that political parties continued to give tickets to persons with very dubious records, including those of serious crimes. Lest it be considered an exaggeration, the 2019 Lok Sabha election had nine candidates who had rape

charges pending against them! It is sad that three of them did get elected.

When requested not to give tickets to such people, political parties claim (a) these people have very high “winnability”, (b) other parties also do the same, if we don’t our candidate will lose, and (c) people vote for such candidates.

The last reason is not correct. Regardless of the number of candidates, only about two or three have a reasonable chance of getting elected and these belong to leading political parties. If a voter does not deliberately want her/his vote to go waste, s/he will have no real choice whom to vote for. Data collected over several elections shows that almost half the constituencies have three or more candidates with criminal records.

This is why the Supreme Court’s observation that political parties will be “forced to accept the will of the people and field candidates who are known for their integrity” becomes important. It is worth noting that the Court did not use words such as “motivated” or “encouraged” but said “forced”!

The problem has been with implementation of the judgment. The Election Commission of India decided, in its wisdom, to implement the letter of the judgment while overlooking its spirit. It provided a NOTA button on the EVMs but did not change the process of deciding the winner. The result is that even if the NOTA button gets more votes than any of the candidates, the candidate with the highest number of votes after NOTA is declared elected. This goes completely against the “will of the people” to which the Supreme Court gave primacy.

Another factor that has prevented NOTA from achieving its full potential is that political parties and their leaders have been actively campaigning against NOTA. They have been asking people not to opt for NOTA because these votes have no impact on who gets elected. This, when the votes polled by NOTA have continued to increase gradually. Several constituencies have seen NOTA getting more votes than the winning margin, the difference between the votes polled by the winner and the candidate who came second. There have also been some, very few, cases where NOTA came at number 2, getting more votes than any of the candidates except the winner.

State Election Commissions

(SECs) who are responsible for conducting elections to panchayats and local bodies and are constitutional bodies independent of the Election Commission, have shown remarkable initiative in this regard. The SEC of Maharashtra issued a notification on June 13, 2018, saying: “If it is noticed while counting, that NOTA has received the highest number of valid votes, then the said election for that particular seat shall be countermanded and fresh elections shall be held for such a post.” While this was a very progressive step, it stopped short of giving NOTA the teeth that the Supreme Court intended. It would be possible for the same candidate to contest the fresh election and the situation could repeat itself indefinitely, frustrating the “spirit” of the Supreme Court’s judgment.

Another SEC stepped in and took the matter further. Just a few months after the Maharashtra notification, the SEC in Haryana issued a similar notification on November 22, 2018. This one said that if “all the contesting candidates individually receive lesser votes than … NOTA …,” then not only “none of the contesting candidates will be declared as elected” but “all such contesting candidates who secured less votes than NOTA shall not be eligible to re-file the nomination/contest the re-election”.

This is what makes NOTA what the Supreme Court wanted it to be. One hopes the ECI will follow the example set by the two SECs, honour the spirit of the Supreme Court’s judgment and the “will of the people”, “forcing” political parties “to field candidates who are known for their integrity”.

Jagdeep S. Chhokar is former Professor, Dean, and Director In-charge of Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad and a founding member of the Association for Democratic Reforms. Views are personal.

Comments

Currently there are no Comments. Be first to write a comment!