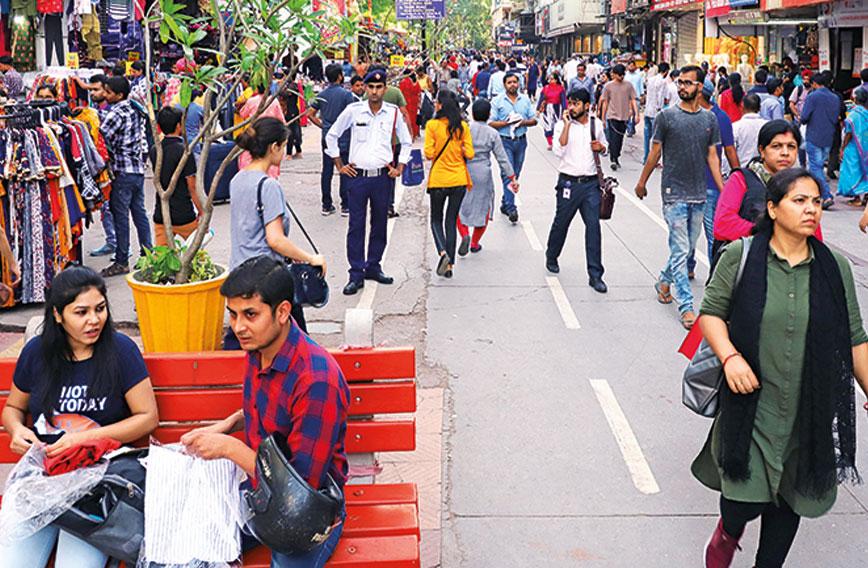

Pedestrianisation arrives in Delhi: Cars have been disallowed in the once-congested Ajmal Khan Road in Karol Bagh | Photograph by Shrey Gupta

Infra is needed but what about smart citizens?

BY SANJAYA BARU

When Delhi’s former chief minister, Sheila Dikshit, passed away there was a spontaneous outpouring of praise for her leadership role in the modernisation of the capital city. Most commentators drew attention to the roads, flyovers, public parks and other such infrastructure development that Dikshit presided over. The media also published photographs of her expressing solidarity with Delhi’s women after the brutal rape and killing of the young woman known as Nirbhaya. If the parks, the flyovers and the Metro are a symbol of Delhi’s modernisation, the high incidence of crime and lack of public safety and cleanliness symbolise Delhi’s dark underbelly. Indeed, most cities present this dichotomy between the modernisation of infrastructure and the persistent lack of modernisation of governance and the quality of living. India is focused on building ‘smart cities’ but India’s modernisation is held back by not-so-smart citizens.

When Delhi’s former chief minister, Sheila Dikshit, passed away there was a spontaneous outpouring of praise for her leadership role in the modernisation of the capital city. Most commentators drew attention to the roads, flyovers, public parks and other such infrastructure development that Dikshit presided over. The media also published photographs of her expressing solidarity with Delhi’s women after the brutal rape and killing of the young woman known as Nirbhaya. If the parks, the flyovers and the Metro are a symbol of Delhi’s modernisation, the high incidence of crime and lack of public safety and cleanliness symbolise Delhi’s dark underbelly. Indeed, most cities present this dichotomy between the modernisation of infrastructure and the persistent lack of modernisation of governance and the quality of living. India is focused on building ‘smart cities’ but India’s modernisation is held back by not-so-smart citizens.

The challenge and promise of urbanisation entered popular political discourse after the turn of the century. The first major national initiative to fund urban renewal and development was launched in December 2005 by the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government and named the Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (JNNURM). The objective of JNNURM was two-fold: first, to encourage state governments to undertake urban governance reform; and, second, to fund urban infrastructure development and improve delivery of public services. The mission was to be funded to the tune of Rs 100,000 crore, with the central government contributing half and states the other half. The inability and, in cases, unwillingness of state governments to fork out so much money for urban development, a politically low-priority agenda at the state level in most parts of India, meant that the centre had to increase its share of funding to two-thirds of the planned mission budget.

The JNNURM was to be implemented over a seven-year period in 65 cities with the programme divided into two sub-missions, namely, (a) Urban Infrastructure and Governance and (b) Basic Services to Urban Poor. In other ‘non-mission’ cities funding would still be provided for identified infrastructure and housing, and slum improvement programmes. At the end of the mission period, in 2012, it was decided to extend the mission to 2015 because a large part of funds remained unspent and little had been achieved by way of governance reform.

Commenting on the implementation of the mission in November 2012 the Comptroller and Auditor-General (C&AG) of India observed that not only had the centre and states taken together failed over a seven-year period to spend more than a third of the planned budget for JNNURM, but many of the governance objectives were never met. The mission was then extended till 2015. Only a mere 10 percent of the 2,000-odd projects that had been approved were actually implemented. The only visible legacy of JNNURM in the nation’s capital city are the regularly stalling public transport Tata buses that create traffic jams every now and then.

Like so many of the UPA’s flagship programmes the JNNURM also transformed itself into a new programme under the National Democratic Alliance government and is called the Smart Cities Mission (SCM). Both in its scope and implementation the SCM has so far had a better track record than JNNURM. The SCM strategy aims to achieve ‘area-based’ urban development through (a) city improvement — dubbed ‘retrofitting’; (b) city renewal — redevelopment; and, (c) city extension (greenfield development). The SCM has an even greater focus on ‘modernisation’ through infrastructure development than the JNNURM.

Taken together, over the past 14 years (2005-19), two successive governments with very different ideological orientation have defined urban development essentially in terms of infrastructure development and modernisation. This is, of course, very important and highly needed. However, urbanisation and urban development also require a concerted effort at modernisation of mindsets and democratisation of urban governance. What has been the record so far?

HARD AND SOFT

Building, development and redevelopment, IT-enabled public services delivery are all features of what may be described as ‘hard infrastructure’. What about ‘soft infrastructure’ of urbanisation? By this I mean governance and public attitudes. The JNNURM had an explicit ‘governance reform’ link to central funding. The central government would fund a state government provided it agreed to implement urban governance reform along with investment in urban development and redevelopment. Few state governments showed any interest in governance reform.

With all major cities becoming state capitals, the chief minister had little interest in letting go of control over the capital city. If every capital city had an elected municipal council and a popularly elected mayor then those manning these institutions of urban government would emerge as influential politicians challenging the dominant position in provincial administration that chief ministers had managed to acquire with time.

Time was when cities like Bombay, Madras, Calcutta, Hyderabad and so on had prominent city politicians elected as mayors. As chief ministers became powerful and as control of urban land, its development and redevelopment became money-spinners for state-level politicians, they had an incentive to eliminate city-level political leaders. The politics and business of urban land use and misuse effectively ended the clout of the institutions of urban governance and made chief ministers and state ministers the arbiters of urban affairs.

Hence, there was no interest at the level of chief ministers and state governments to implement the governance reform agenda of the JNNURM which required rejuvenation of elected offices at the city level, including an elected mayor and a municipal council. Delhi was among the few cities that had a democratically elected city head but by turning a city into a state and a mayor into a chief minister, Delhi allowed a disservice to be done to its governance. Delhi’s chief ministers are no more than city mayors. But because of the high-profile nature of such a position in the capital city, Delhi’s CMs have had a fancy view of their political importance.

The second soft side of urbanisation is civic sense. The most important governmental initiative in this regard has been Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s “Swachh Bharat” mission and the campaign to build and use public toilets and ensure clean and green city development. While this initiative has made good impact in some cities, especially where state and local governments have been active, in the end its effectiveness will depend on the civic sense of every citizen. This is where India still lags behind many countries at a similar level of development. And this is precisely the terrain for action of civil society organisations.

In the locality where I live in Delhi it is voluntary neighbourhood activism by concerned citizens that has transformed public spaces around my home. The locality has become more green and clean purely on account of voluntary work done by its residents in their free time. On the other hand, a small nearby market with around 10 or 12 shops catering to the neighbourhood remains filthy and badly maintained because none of the shop owners is interested in ensuring the proper maintenance of common areas. Within a span of a couple of hundred metres one can see the beneficial consequences of citizen ownership of public spaces and the negative impact of the lack of it.

In the end, urban governance has to be a compact between local government and citizens. Unless local governments are financially and administratively empowered they will not have the commitment or the capability to deliver to their citizens what is expected of them. In India, we have so far focused more attention on modernisation of the hard infrastructure of urbanisation and not enough on the soft dimension of public attitudes to it. To create and maintain smart cities we need smart citizens.

Sanjaya Baru is a writer and Distinguished Fellow at the Institute for Defence Studies & Analysis in New Delhi

Comments

Currently there are no Comments. Be first to write a comment!