Thank you, Bahugunaji! You changed me forever!

By Rahul Ram

I met Sunderlal Bahugunaji in May 1980. About 20 teenagers from Delhi accompanied by one adult, descended on his ashram at Siliyari in Garhwal. We were young, keen proto-environmentalists, city slickers who had by and large never spent any significant amount of time in a village.

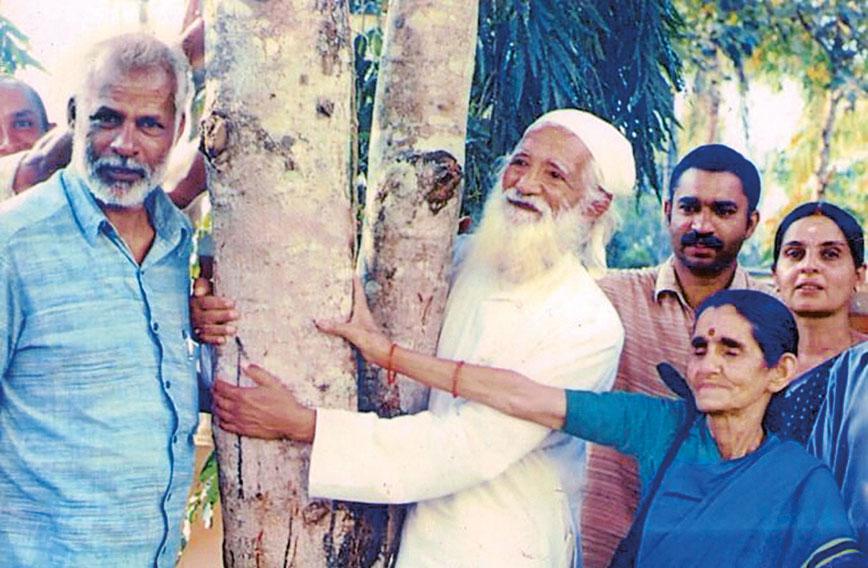

Bahugunaji’s recent passing away at the age of 94 after being infected by the virus, brought back memories of that visit to his ashram all of four decades ago and what it meant to us to meet the soul of the Chipko movement and hear his message of conservation in the very surroundings where it had evolved.

The world had discovered environmentalism over the last 15 years as the twin depredations of development and population growth made their effects apparent.

Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring and Paul R. Ehrlich’s The Population Bomb became must read books as did The Limits of Growth written by a group of thinkers, scientists and economists known as the Club of Rome.

Governments responded by setting up ministries and departments of environment passed the Clean Water Act and the Clean Air Act. In India, the Silent Valley Project became a rallying point.

In all this, the people of the villages of India were not seen or heard. Worse, they were often painted as ignorant villains who had too many children and cut down the forests around them.

Enter the Chipko movement. We kids heard about women hugging trees to prevent them from being cut and we heard about the person who was carrying their message to the world. And so, we came to Sunderlal Bahugunaji’s ashram at Siliyari.

A patient, ever-smiling man, he explained to us the deep links of local people to their environment. He told us how the British had replaced the lush natural oak-rhododendron forests of the region with monocultures of pine to satisfy the needs of the paper and pulp industries.

The pine forests that yielded neither fruit nor fodder for their acidic needles allowed almost no undergrowth. He talked about how the people were shut off from 90 percent of the land around them. And how water sources started drying up. And how younger men left villages leaving behind women, children and old people. He spoke about the incredibly hard life the women led, spending hours searching for fuel, water and fodder while having to run their farms and households.

And then he told us how local people were fighting back. How they were trying to conserve the remaining forest, how they were enclosing a few square metres of land to allow the forest to regenerate. And how this improved local water sources and provided sustainable sources of food, fodder and minor forest produce.

Above all, he taught us how imperative it was to place local people at the heart of any attempt to restore and protect the environment.

We walked 250 km over the next two weeks, staying at a different village almost every night. For us city slickers this meant various adjustments. There was no indoor plumbing so we were introduced to the pleasures of a crap with a view. ‘Aap fresh ho gaye’ or ‘Aap fresh ho lijiye’ were the euphemisms used by Kunwar Singhji who was our guide for the trip.

Then there was the food. Thick rotis with watery potato or very often lauki (ugh). You ate what you got and were hungry and thankful. Tasteless dalia. And then the cups of chai at roadside stalls except that it was served in large metal tumblers too hot to touch. A precious biscuit or mathi with it since none of us had brought enough money.

There was no bathing for days on end as the water was cold. Finally, one sunny day we bathed in a mountain stream, freezing our butts off and then lay on the warm rocks like lizards basking in the sun.

One magical day we attended a meeting of the Chipko Andolan. We climbed down a steep cliff to a stream and were startled by an extremely large monitor lizard (Varanus) up to three feet in length who regarded us with unblinking curiosity.

The meeting itself had a lot of speeches in Garhwali that we barely understood. We were introduced to the crowd as proof that the voice of the movement was finally being heard in Delhi.

But the highlight of the meeting, at least for me, were some songs sung by a local folk legend, Ghanshyamdas Salianji. He sang:

“Swarg Uttarakhand bhumi

hamara dev Uttarakhand bhumi

Himalaya phool jaiso bhramhikamal

Himalaya dhanna devdaro bhramhikamal"

To the tune of a very famous folk tune ‘bera pako baromasa’.

The song remained in my head and I can and do still sing it 41 years later!

This trip was instrumental in changing my world view and pushed me towards doing my Ph.D in environmental toxicology and then into the Narmada Bachao Andolan a decade later.

Indeed, some of the young people on that trip have gone on to become activists and academics who work on environmental issues. We understood by first-hand interaction what Bahugunaji was trying to tell the world.

Thank you, Bahugunaji, for transforming the life of a 17-year-old boy.

Those 15 days were life transforming for a lot of us. For me it opened up a new way of thinking about the world. Thank you, Bahugunaji!

Rahul Ram is a founder-member of Indian Ocean

Comments

-

Amit Kumar Bose - July 20, 2021, 10:14 a.m.

A lovely ode to Bahuguna ji! I too was of the same impressionable age and a regular forest traveller. Ever since Chipko I can never let a large tree trunk go by without a tight hug! It feels like my mother is hugging me back.