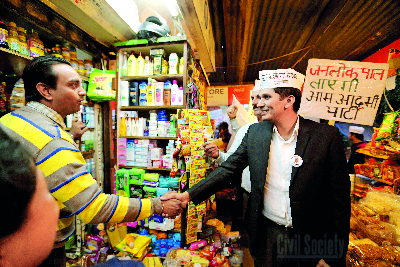

After the first election victory: The slogan was 'Desh ka neta kaisa ho. Aam aadmi jaisa ho' | Civil Society picture/Lakshman Anand

Activism to politics: AAP in office and in the streets

By Umesh Anand

IT was a chilly January morning in 2014. People were converging on the secretariat in Delhi, the seat of power of the state government that runs the capital city and its peripheries. A Janata Darbar, or public assembly, had been scheduled. Citizens would get to meet ministers and elected representatives of the Aam Aadmi Party, which had just days earlier had its first taste of electoral success.

From being activists in the streets, the AAP leadership had been catapulted into office. They wanted participatory governance to be their hallmark and the Janata Darbar was meant to show that they were up for an open and responsive administration. Citizens could meet their leaders with complaints and suggestions and be assured of a hearing, if not solutions.

People arrived at the Janata Darbar in droves from far and wide, Delhi being a city of 20 million with a large and varied urban footprint. From the very poor to the middle-class, they were all there. They brought with them a deluge of concerns ranging from a missing child to inflated electricity bills, water shortages and bad roads.

Despite the best of intentions to make it productive and useful, the Janata Darbar quickly descended into chaos. Arvind Kejriwal, then chief minister for the first time, was in the midst of the action, commendably meeting people and looking at files. But it soon became apparent that the Janata Darbar was going nowhere.

As the pressures mounted, Kejriwal suddenly withdrew from the open area where people were milling and went inside the secretariat. He emerged only much later to address the crowd from atop the building and assure them of follow-up action.

It has been a decade since that adventurous Janata Darbar. Over these years, AAP has become seasoned in office. Its activist ambitions have been tempered by the realities of governance. Remaining in power has become a priority as it must for people in politics. How good is that is the question.

A case of corruption in issuing liquor licences has landed both Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal and his trusted deputy, Manish Sisodia, in jail. AAP’s image as a party with a difference has been dented.

A day of reckoning confronts AAP’s leaders unlike anything they could have imagined. The liquor licences are the focus of attention. But there are additional problems brought on by an unfriendly and powerful Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) regime at the Centre.

Despite big electoral victories and a decade in office, the AAP-run state government in Delhi has been rendered dysfunctional. Kejriwal’s arrest on the eve of elections, though the liquor licensing case is two years old, is also seen as vendetta by the BJP.

PARTY OF ACTIVISTS

In politics, there is always the rough and tumble to contend with. But there is much more attached to the rise or decline of AAP. It is a party of social activists who have made the crossover to politics. They have come to power by raising the issues of inclusive development and transparency.

The question now being asked of AAP is whether it has done enough to live up to its promise of ushering in new politics or whether it has betrayed the goodwill it received and become just like any other party.

In Delhi, AAP has a clear record of improving government schools and hospitals, taking very basic healthcare to neighbourhoods by way of Mohalla Clinics, putting electric buses on the road, reviving water bodies. The AAP government is credited with reducing local-level corruption and the use of speed money. Its giving of free water and electricity can be criticized as populism instead of genuine development. But the fact is that it has had three terms in office in Delhi with many of its MLAs getting repeatedly elected.

|

|

|

On liquor shop licences, the allegation is that there have been kickbacks. But it is complicated and contradictions abound. Though they face charges, no one would accuse Kejriwal or Sisodia of personal corruption. There has been no trace of the money that is alleged to have changed hands.

For the longest time NGOs and activists have flirted with politics. Some have stood for election themselves with dismal results. Others have tried to put up their own candidates. Under Sonia Gandhi’s National Advisory Council (NAC), they had their say. The RTI, MGNREGA, disabilities, forest rights, food security and street vending laws were ushered in.

But it is only AAP that has made the big leap directly into politics, getting elected three times in Delhi. It is also in power in Punjab. There are votes to its name in Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, Goa and elsewhere.

Further proof of AAP’s success in politics is seen in larger parties in opposition seeking to ally with it. Efforts by the BJP to script AAP’s premature demise also indicate its growing political footprint. Why else would efforts be made to put the party down?

FRESH TALENT

AAP came out of an anti-corruption movement which questioned telecom licences and Commonwealth Games contracts. It captured the imagination of people with its message that stopping corruption would lead to better development and quality of life.

|

|

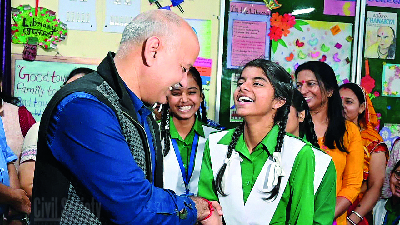

Sisodia at a refurbished government school with happy children | Civil Society picture/Shrey Gupta |

It brought new faces into politics — middle-class talent which had earlier shied away from political involvements, considering them to be messy and difficult to handle. Since the beginning, several AAP members have come and gone as might happen in any organization. Three of the AAP co-founders were shown the door by supporters of Kejriwal and Sisodia in a messy episode in the early days.

But AAP’s hallmark was and remains the talented, well-educated and public-spirited people it attracts in leadership roles. The clean faces that represent it have much to do with the image that it enjoys.

Added is the fact that Kejriwal and Sisodia have been known to live and conduct themselves simply despite the positions of power they have held. Kejriwal gave up a career as an income tax officer and has an engineering degree from the Indian Institute of Technology. Sisodia came with a media background.

When it was launched the party stood out with its opposition to the VIP culture in Delhi such as the use of red lights on cars and flaunting of privileges. It was this that provided an immediate connect with voters fed up with the high and mighty ways of India’s politicians. It remains at the heart of the party’s identity. After the first election success, the slogan at the victory rally was: “Desh ka neta kaisa ho. Aam aadmi jaisa ho. (A leader should be like an ordinary man.)”

Despite the imprisoning of its leaders and the ruling BJP’s efforts to finish the party, AAP has a reservoir of goodwill that will take some time to deplete. Only a vote will finally tell how much support AAP has after the current allegations against it. But the party’s capacity to enthuse people even in the absence of its top leaders was on full display at an opposition rally in Delhi. Thousands of people filled the Ram Lila Ground and seemed to have showed up willingly. It proved AAP’s connect with its voters in Delhi.

The EARLY DAYS

Kejriwal and Sisodia were part of the RTI movement in India. As activists they worked for transparency and accountability in government. Through Parivartan, the NGO Kejriwal founded, municipal works were assessed for quality. Road samples were collected and sent for testing. Ration shops were held to account, forcing the then Congress state government in Delhi to monitor supplies of grains so that they weren’t siphoned off.

Saurabh Bhardwaj, a software engineer who joined AAP and became an MLA | Civil Society picture/Lakshman Anand |

They worked on the ground against great odds. Politicians didn’t take them seriously and they had to strive to make their presence felt. Local vested interests pushed back, causing harassment and even physical harm. But activists of Parivartan plugged away and went that extra mile going from one jan sunwai or public hearing to another to highlight the complaints of the poor in Delhi’s slums.

It wasn’t easy. This magazine remembers Kejriwal spending several hours alone in a police station answering trumped-up charges against him by ration shop owners or was it by municipal contractors. Sisodia trekked all the way to our door in Gurugram on a scorching May afternoon for help to redesign Apna Panna, an activist newspaper they were bringing out so as to reach their message to people all over. It seemed they were indefatigable.

They were, however, not without support from more seasoned campaigners like Aruna Roy, Nikhil Dey, Shankar, Jean Dreze, Shekhar Singh and others. At its height the anti-corruption movement projected Anna Hazare. So effective was this that middle-class people would come to protests with their children, saying they had come to see a second Mahatma Gandhi! Such was the mood in those days that Hazare acquired that kind of aura.

Seen in this way, the foundational blocks of AAP have been fashioned over 20 years. Embedded in its DNA are the social concerns that were highlighted through multiple agitations. As a party, however, it is new in an organizational sense. It also shoulders the burden of an adverse equation with the established parties.

Elections cost money, for instance. Getting one’s message across is also challenging because of the Indian media’s obsession with size and its eagerness to protect the interests of the establishment. There is no level playing field and the big parties have an unfair advantage. If today AAP is visible, it has had to fight for every inch of space it gets.

It is to AAP’s credit that it has survived and persisted with its efforts. AAP has managed, despite ups and downs, to retain its identity, if not the old aura, as a party with a difference — an alternative to the established parties. Now, with its teaming up with the Congress, perhaps that will change even if it is for their shared goal of reining in the runaway dominance of Narendra Modi.

START-UP CULTURE

The avowed purpose of AAP has been to cleanse politics and improve public life. To achieve that it has had to cause disruption but also play the game as it is played. It is interesting how much support it has received from ordinary folks who have been donors to its cause. AAP has a natural constituency of people who want to set the system right.

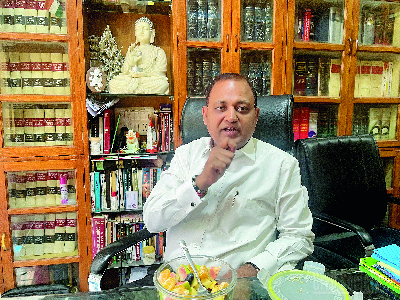

Somnath Bharti, a lawyer by profession and AAP star, successfully represents Malaviya Nagar in the Delhi Assembly | Civil Society picture/Umesh Anand |

We meet Somnath Bharti in his lawyer’s office up two flights of stairs in a tacky building just off Malviya Nagar Market in South Delhi.

Bharti is a first-time politician who has won the Malviya Nagar Assembly constituency three times as an AAP candidate. His voters love him because he is always at hand to help them with matters big and small. He is articulate and friendly and has none of the repulsive trappings that many politicians tend to flaunt. He will be contesting the New Delhi Lok Sabha seat in the coming parliamentary elections.

It is a much bigger constituency than the Assembly seat he represents, but Bharti has built a reputation for himself. He will be drawing on an enormous reservoir of goodwill.

Asked why he didn’t join an established party instead of going with AAP, Bharti says there would have been no space for him. AAP gave him the opportunity he wouldn’t have otherwise got. There was also the heady experience of being part of a unique effort to bring change in the country.

“In the bigger parties it is difficult to come up. You won’t get a ticket. There are several interests involved. Being educated and honest and driven by higher values aren’t the best qualifications in those parties,” says Bharti.

He concedes it is a huge challenge to raise funds to fight elections if one is not involved with wheeling and dealing. Bharti finds his way around it by raising small donations. In this way donors don’t have expectations because small amounts get written off. There are well-wishers who print his posters as a contribution or provide him transport. Others will volunteer to campaign and be in position at booths. Bharti’s strength is the bond he has with his constituents.

“I am for state-funded elections,” says Bharti. “The BJP has hundreds of crores of rupees to spend on social media and AAP has a paltry budget. There should be equal access to resources. A level playing field is needed.”

COMPULSION OR CHOICE?

Bharti is perhaps a good example of how to beat the system while being part of it. But his is just one seat. As the national ambitions of AAP have grown, the curve has gotten steeper. The need for resources has multiplied while trying to make its presence felt across states. How does a fledgling party manage to survive in such adverse circumstances?

Prof. Jagdeep Chhokar of the Association for Democratic Reforms says compulsions of a bad system cannot be an excuse for doing things like other people do.

“I would not agree to the word compulsions. These are choices people make. Nobody forces anybody to get into politics, and once in politics nobody forces anybody to do things that people do. I very strongly disagree. I think these are choices people make,” says Chhokar.

Dr Jayaprakash Narayan set up Jansatta in Hyderabad in 2006 because he believed politics could be reformed. Politicians needed help to be honest and genuinely serve people. It was important to engage with politicians, trust them and give politics a better standing in the public eye.

Jansatta has been consistently funded through donations. While it initially evoked public interest, it has steadily languished over the years. Its mission of improving politics is far from met.

“A level playing field is needed,” says Narayan. “The answer is in state funding of elections and transparent support from donors. There is enough money in the country. to fund good parties.”

EFFECTIVE FROM OUTSIDE

Getting into politics is fraught with problems, fundraising being just one of them. On the other hand, NGOs and social activists with political beliefs, but no direct engagement as politicians, are also effective.

Chhokar recalls meeting Aruna Roy in his office at IIM Ahmedabad in 2000 and saying to her: “Look, politics is a very dirty game and I have nothing to do with politics. And she said : You cannot say you are not in politics. You are in politics even if you don’t vote. You are in politics because you are allowing somebody to vote for you.”

Says Chhokar: “You may not be in competitive electoral politics, but you are in politics. Every citizen is in politics.”

Chhokar says there is a difference being in competitive politics and being a political activist. But there is no difference between being a social reformer and a political activist because politics is part of social activity.

He says it is “theoretically possible” to reform the system from within. The challenge comes in making those choices that don’t perpetuate the system.

“Today, Indian politics is such that anyone who has entered politics, competitive electoral politics, gets swept away. Once you are in the fish bowl you have to rely on the same feed that everyone else uses,” he says.

ADR is an example of a voluntary organization bringing change to politics without being in politics itself. It has successfully fought its way through the courts to ensure declaration of assets by candidates, their criminal records and most recently it had the electoral bonds put in the public domain.

Being politically engaged but not in politics comes with its advantages. Compromise is not required. It also becomes possible to deal with players across the political spectrum.

DEALING WITH ALL

Nikhil Dey of the Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan (MKSS) believes that many of the issues and the groundwork done by activists and people’s movements has been used by AAP to launch itself in politics. RTI and the need for transparency in government is of course the key one.

Dey says: “As a social activist you are outside and connect with everyone. You don’t have to be partisan. I’d say we have a very strong ideological position. We state that. In a democracy, it is the job of the government in place to talk and engage. We engage regardless of which party sits in government. We will try and make sure that in the role that we play as social movements, as social activists, governments do not overstep the Constitution.”

“The right to information allows citizens to engage officially every single minute. On every single decision, all the time, not once in five years,” says Dey.

“I think as activists we have really played out a new kind of very important politics. But I don’t want to make this sound as if we’ve got all the answers,” says Dey, “because it is eventually the party in power that decides the agenda of what will go to Parliament, how it will come through Parliament. Often we see issues we have decided on getting diluted.”

Being a politician in power, says Dey, may in fact be less of an advantage than being an activist because of limitations and compromises that come from being in office.

The story of AAP mirrors many of these observations. Leaving the heady days of raw activism behind, the party from its very early days had to contend with the realities of being in office. It has survived, despite the odds stacked against it, so far.

You might also like to read:

AAP and beyond: Broom as lightning rod

AAP's volunteers figure out what's wrong at govt schools

Importance of being AAP and earnest

Comments

-

Saurav - April 30, 2024, 11:20 a.m.

Nikhil Dey's perspective on how being a powerful politician may actually be less advantageous than being an activist really fascinated me. Our country does not have dearth of bright minds. If they can come together for good governance, things can be brighter for society at large.

-

Mayura Dixit - April 30, 2024, 11:17 a.m.

Brilliant perspective! Really need more balanced media of this kind in the times we live in.

-

Atin Kumar - April 30, 2024, 11:15 a.m.

Thank you for writing about this without it being one sided. It is important to engage in political discourse without being aggressive or loud. That is just what this cover story does!

-

Akanksha Tiwari - April 30, 2024, 11:13 a.m.

What I like is how this is a neutral perspective. In times where we have media trying to desperately shape political opinion, this came as a breath of fresh air. No one party can ever be all bad or all good. There are always going to be shades of grey in a country so diverse and densely populated. We need intelligent, sound and balanced minds at the forefront.

-

Gaurav Singh - April 30, 2024, 11:08 a.m.

Such an insightful read! I really learned a lot, especially about the background of AAP and how it all began. I admire the way giving up was not an option. India needs parties that can stand up to the current regime, and despite the choppy waters, AAP can well be one such alternative even today.