SHREE PADRE

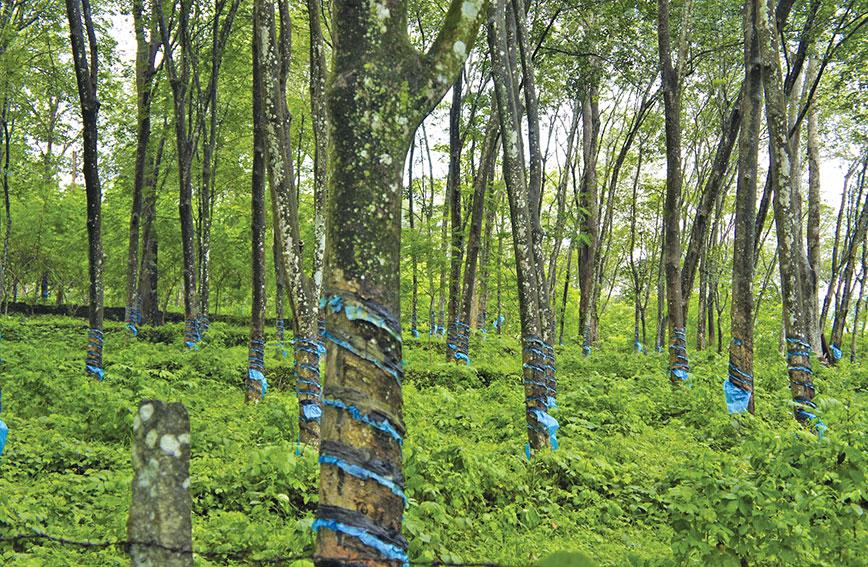

MEenachil and Kanhirappally taluk in Kerala’s Kottayam district are considered the ‘rubber capital’ of India. It was from here that rubber cultivation spread across Kerala and subsequently to different parts of India. Kerala went on to produce 90 percent of the country’s natural rubber.

Surprisingly, in recent years, rubber is being replaced by jackfruit here. Rony Mathew, chairman of the Agriculture Products Processing and Marketing Cooperative (APPMC) in Pala, Kottayam district, says that in the past three years about 100 acres of jackfruit plantation have replaced rubber trees.

In 1954, Mathew Thomas Thakadiyel started India’s first rubber tree nursery in Pala. Seven decades later, his son, Rony Mathew, has started a jackfruit nursery instead, under the auspices of the APPMC. In three years, the cooperative has sold about 25,000 jackfruit grafts.

In the first week of January this year, P.C. Chacko, a 73-year-old farmer, was honoured at a jackfruit festival held by APPMC in Pala. Last year, he cut down rubber trees on 10 acres and planted jackfruit instead. He explained that he didn’t see much of a future for rubber. Jackfruit requires less labour, starts yielding fruit in three years and has an assured market. Even if a single jackfruit sells for `50, he will earn `1,50,000 from one acre after seven years, said Chacko.

Why is an industrial cash crop being replaced by a humble food crop? Let’s look at price estimates. Around 2005, the price of rubber rose from `200 per kg to `240. But by 2012, prices began nose-diving and declined to `100 per kg. Currently, the price of rubber hovers at around `140 per kg. Farmers complain that this figure doesn’t even meet their production cost. An estimated one-fifth of rubber estates have stopped tapping activities as owners say it is not feasible financially.

The interest in jackfruit is not a sudden development. Since two decades, a huge quantity of tender jackfruit is being sent to north India from the Pervumbavoor area. To widen their supply chain, traders began to look for jackfruit in Ernakulam district in Kerala’s rubber belt. Though the traders rip off all jackfruit from trees and pay poorly, there is an assured market.

This is the reason why farmers like Jaison from Uloor are planting jackfruit. The traders pay `25 per jackfruit currently and Jaison believes these prices will go up year by year.

Farmers have also been exposed to the benefits of growing jackfruit. GRAMA (Group Rural Agricultural Marketing Association), the first farmers’ group that started value addition of jackfruit in 2006, is located very close to Pala. Four years ago, GRAMA took a busload of farmers on a study trip to Panruti, the jackfruit paradise of the country. For the farmers, it was their first ever exposure visit — to study jackfruit farming. The activities of GRAMA amply proved to the farmers that they could earn an income from jackfruit.

The APPMC, started three years ago, is buying jackfruit from local farmers and processing it minimally as frozen raw jackfruit. Last year, it sold 20 tonnes of frozen jackfruit to exporters. The consignments went to the UK, the Gulf, the US and other countries populated by people from Kerala. The main reason for this demand is the low glycemic index of raw jackfruit, making it ideal for diabetics.

The cooperative has been buying raw jackfruit for `7-8 per kg. Last year, it bought 110 tonnes of whole fruit. Employing about 100 staff, the cooperative got the jackfruit processed in five centres. This year, it intends to buy 200 tonnes. It has also conducted six workshops on jackfruit farming.

Besides, being a food crop gives jackfruit an advantage. In Kerala, jackfruit is a staple food, consumed as a stir-fry (chakka puluk) especially during the jackfruit season. At least one meal a day or two meals a week are cooked with jackfruit instead of rice and consumed with meat or

fish curry.

The APPMC held its first three-day Jack Fest in Pala in January this year. On day one, 108 kg of frozen raw jackfruit flew off the shelves. The canteen, in three days, sold 1,200 chakka puluk dishes for lunch. Inspired by its success, the APPMC has decided to hold an annual Jack Fest.

Awareness of the health benefits of jackfruit has also spread. Locals now consider jackfruit to be a healthy food. Not only is it beneficial for diabetics, recent media reports indicate that it prevents cancer and has good dietary fibre. Locals say the older generation has fewer lifestyle diseases because they consumed jackfruit regularly.

Another major attraction for farmers is that jackfruit cultivation is less labour-intensive than rubber and doesn’t require too many inputs like manure. Harvesting is the only major operation, they say.

Farmers are planting only one or two selected varieties of jackfruit so that they can begin supplying to the agro-processing industry. Everyone believes their jackfruit trees will yield fruit from the fourth year and bring them a higher income from the seventh year onwards.

Farmers also see environmental benefits in shifting from rubber to jackfruit. Not only is it a food crop, it represents crop diversity, retains rainwater and is a measure to fight global warming. The jackfruit tree is known to cool the microclimate considerably.

Thomas Kattakkayam, who has an impressive varietal collection of jackfruit, welcomes the new trend. Rubber exploits groundwater whereas jackfruit does not lower the water table. “I have cleared one acre to house my genepool of jackfruit. If the phone calls I get demanding jackfruit grafts are any indication, rubber might extend to 1,000 acres in a year or two,” he says.

But the agriculture department and research institutions including agriculture universities have not woken up to the changing reality. They are not ready with information such as the right cultivars, how to do canopy management, thinning and so on.

The president of GRAMA, Joseph Lukose, warns that all varieties of jackfruit are not suited for processing. “The agriculture department has to do varietal selection to identify cultivars best suited for processing. Secondly, it has to make serious efforts to standardise value-added products.”

But the changeover from an industrial cash crop to a food crop is being welcomed. S. Ushakumari, the executive director of Thanal, an organisation working for sustainable agriculture, agrees that for the economy and for agricultural sustainability this is a good trend. Except that jackfruit should not become a mono-crop like rubber.

Comments

Currently there are no Comments. Be first to write a comment!