The Wanarmares are a primitive tribe that settled in Goa

Beaten, threatened tribals find succour

Gauri Gharpure, Ponda | Photographer: Samrat Bandodkar

About half an hour from Ponda in south Goa, an undulating road leads to a village called Nirankal. Here, on a hilltop, Wanarmare tribals settled around four years ago. They made flimsy huts propped up on bamboo poles. The floor was plastered with cow dung. With no walls, it was the roof covered with tarpaulin sheets that saved them from Goa’s torrential monsoon.

On 16 October, when most Wanarmare families had left to find work, a mob from a nearby village ransacked their huts. The FIR report, filed on the night of 18 October, alleges that all tarpaulin sheets were pulled off, solar light panels donated by the state government were broken, some huts were pulled down, water barrels were emptied and broken, and that large amounts of rice gruel boiling on twigs in makeshift chulhas were overturned.

The villagers threatened the tribals with eviction. One woman was injured in the mayhem. The FIR names two people, a man and a woman. The man was taken into custody and granted bail the next day. The police did not arrest the woman, saying that nothing was to be recovered from the site under Section 41A.

The Wanarmares are a tribal community originally from remote parts of Maharashtra. They were expert hunters especially adept at catching monkeys, and hence the name. Some groups of Wanarmares settled in Goa decades ago — in Bicholim and nearby northern regions, apart from Nirankal in Ponda, south Goa.

Trouble was brewing in Ponda for a long time. On 2 October, some villagers came to their settlement and ordered them to leave. On 8 October a few Nirankal villagers met the district collector and the industries minister and local MLA, Mahadev Naik, with demands to evict the Wanarmares, calling them ‘dirty’ and ‘a nuisance’. About a year ago, the Bethoda panchayat had passed a resolution to evict the community from the village.

They have been living in flimsy, makeshift huts

They have been living in flimsy, makeshift huts

Last year, ration cards were issued to these 17 households. Some families also obtained Aadhar cards and they were in the process of getting registered for voter cards. This, many people say, is the chief bone of contention.

The Nirankal panchayat stands on an uncertain majority and the slightest change in equations may result in a change of political leadership at the panchayat level. Others are of the opinion that a builder is eyeing the prime location on which the Wanarmares now live and is being backed by a local politician.

The 17 Wanarmare families with 44 children and six infants have faced the brunt of the attack and live in fear. The incident has all the elements of conflict that still trouble many parts of India: bullying, criminal intimidation, forceful eviction, social boycott, land-grabbing and political motives.

However, something stood out this time — the outreach of civil society. A small group of people on a WhatsApp group brought the issue onto the front pages of local Goan dailies. Through an unusual mix of persuasion, dialogue and coordination between different sections of bureaucracy, the group is ensuring that the administration and political authorities are held accountable and extend help within their jurisdiction.

Advocate Satish Sonak has been at the forefront of this movement. On 1 November he brought this case to the attention of the Human Rights Commission. The commission passed an order to the district collector of Ponda, stating that solar panels be fixed, food provided as well as clothing and security, as quickly as possible. A compliance report has to be submitted in a fortnight.

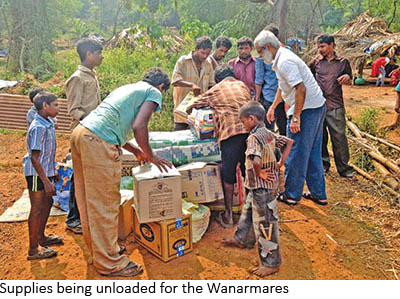

Swift action followed these directives. The same evening, a water tanker was sent to the Wanarmare settlement. On 2 November, in accordance with the Human Rights Commission’s order, the deputy collector and SDO, Ponda, directed the civil supplies inspector to provide immediate relief ration. Four officials reached the site around 5 pm and distributed 380 kg rice and 30 kg sugar.

A medical camp arranged by volunteers found the children were malnourished

A medical camp arranged by volunteers found the children were malnourished

Donations in kind were sought at once after the attack and a list of items for immediate relief was compiled. Vaman Bhate, owner of Panjim’s Varsha Bookstall, agreed to collect items and his shop became the first drop-off point for donations. People began pledging items from the list and dropped cardboard boxes at Varsha Bookstall. Every day, cars would collect the items, drive down to Ponda and deliver them to the Wanarmares.

Not all was rosy, however. Some people allegedly started spreading rumours that too many used clothes had been collected and the tribals were burning them. There were whispers about cash being solicited. The collector sought information. Journalist Prakash Kamat clarified that both rumours were wrong on 3 November.

The same day, a group of 10 eminent artists including Harshada Kerkar, Shridhar Bambolkar, Ajay Kothavale, Prashant Nageshkar and others took part in an art camp in Ponda on the theme ‘Goa — Land, Life and Legacy’ and spent time with the community. They painted at Nirankal all day. They plan to hold an exhibition and donate all the proceeds to the Wanarmares.

On 4 November, representatives of the Wanarmares met the Women’s Commission, the Child Rights Commission and the Commissioner of SC/ST Rights. They submitted a letter requesting speedy justice and relief. There is confusion regarding the legal status of Wanarmares as SCs/STs. This results in several loopholes and delays by the bureaucracy. The police argued that since they were tribals, the FIR had to be routed through the DYSP, Tribal Affairs, and sorting this out took time till the night of 18 October. The chairperson of Goa SC/ST Commission, Anant Shirvoikar, said that he would do all he could on humanitarian grounds since the Wanarmares are not officially notified as STs.

The Wanarmares’ makeshift settlement is interspersed with marigold plantations. Orange floral blobs are the only blob of colour on this rocky hillock. When asked if they planted flowers to sell them, Sugandha replied in a broken mix of Konkani and Katkari that they did, but most locals refused to buy the garlands they make. “And the police asks, where is your licence? If we don’t work they say we are dependent and if we try to be independent they don’t like it,” Sugandha said, rolling her eyes more in sorrow than criticism.

The women walk a kilometre every day to fetch water. Their children are being sent to school for the first time. The eldest kids are studying in Class 3. They walk about five miles every day to reach school. One child wanted a school bag, another asked when the solar lights would be fixed so he could study. They don’t have electricity connections. Their settlement is crawling with red ants. At night there are snakes and scorpions around. Yet, most of the children are barefoot. Gopal, a Wanarmare man helping with coordination, said that most families buy one pair of chappals that are shared by four or five children.

The women walk a kilometre every day to fetch water. Their children are being sent to school for the first time. The eldest kids are studying in Class 3. They walk about five miles every day to reach school. One child wanted a school bag, another asked when the solar lights would be fixed so he could study. They don’t have electricity connections. Their settlement is crawling with red ants. At night there are snakes and scorpions around. Yet, most of the children are barefoot. Gopal, a Wanarmare man helping with coordination, said that most families buy one pair of chappals that are shared by four or five children.

Yet the Wanarmares accepted help with great restraint and dignity. The women hesitantly stated what they needed. One woman moved her shoulders nervously and said: “We want old clothes to use during our periods. The ones we have are too tattered.” She refused sanitary napkins, saying they won’t be able to afford them later. An elderly woman then cleared her throat and asked for “blouse, petticoat and a saree”. Sugandha immediately interrupted her. “But we have that,” she said, pointing to the faded, tattered clothes she was wearing.

Volunteers also arranged a medical camp. A series of health complications in children and women were revealed. Medical vans were quickly arranged for preliminary check-ups, diagnostic tests and follow-ups. One child was diagnosed with a heart murmur, another showed signs of an enlarged liver. A few children suffer from cold, fever and malnutrition. Three women suffer from severe post-partum problems. Two prominent medical stores in Ponda and Panjim offered free medicines. Government aid of Rs 4,500 per family has been deposited in their bank accounts.

But civil society groups say this amount is insufficient and are negotiating for more. There are plans to embed two social work students as part of their college projects with the Wanarmares for at least two months. Their travel and accommodation arrangements will be taken care of by volunteers from civil society.

The flood of goodwill was such that civil society groups decided to withdraw help in kind and closed all collection points in Panjim, Ponda and Mapusa on 6 November. Now, the focus has shifted to health, with some children diagnosed with serious ailments that need immediate intervention. On 11 November, the electricity department began work to instal streetlights in the area; water and electricity connections for the Wanarmares are likely to be given soon if social and political will prevail.