The marginalised mother

Kavita Charanji, New Delhi

The choicest epithets – wicked, mean, cruel – are often flung at hapless stepmothers. Such stereotypes are reinforced by a barrage of regressive TV serials, films and epics that portray the stepmother as the scheming other woman who has dislodged a haloed biological mother from her pedestal.

Then, there are all those fairy tales about the wicked stepmother like Cinderella and Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. At a very tender age children get brainwashed into believing such tales are for real.

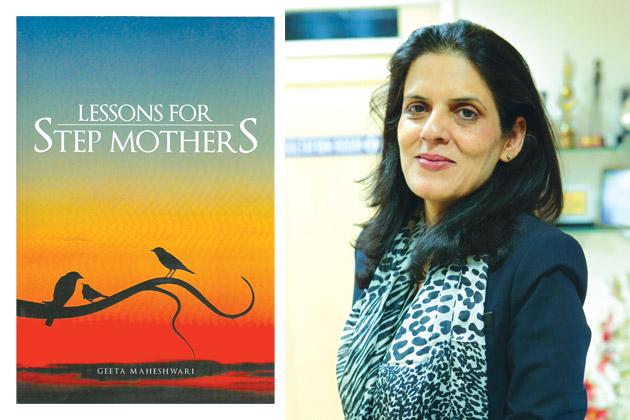

The gentle Dr Geeta Maheshwari, marriage and remarriage therapist and a stepmother herself, is treading a difficult path. She is trying to sensitise society about how tough it is to be a stepmom and giving strength to the marginalised stepmother.

In her slim book, Lessons for Step Mothers, Maheshwari describes the complex dynamics at work in a step family and offers calm words of advice for those daring women who become stepmothers or are contemplating becoming one.

“Many a stepmother has come to accept society’s perception of her. So she overstretches herself to prove that she is a good mother,” says Maheshwari. Meanwhile, the new family, particularly stepchildren, are often hostile, rude and obnoxious.

The stepmother is confused and lonely since she cannot share her pain with anyone for fear of the “I told you so” syndrome. She falls into ‘stepmother depression’.

In the process, she becomes a nervous wreck and her remarriage is jeopardised. It is a losing battle. Somewhere the survival instinct takes over and she starts distancing herself from the family. “Every stepmother’s marriage that breaks down only reinforces the myth of the wicked stepmother,” explains Maheshwari.

A breakdown in marriage can be avoided if women are adequately prepared for the difficult, and often thankless job, that awaits them. Maheshwari’s book contains useful chapters like ‘Unpack your baggage’, ‘Look before you leap,’ ‘Managing money,’ ‘Take care of yourself,’ ‘Vent if you must,’ and ‘Your husband’s role in your journey.’

As a stepmother herself, Maheshwari is not just a ringside observer of the tough job stepmothers try to do. Women, she points out, tend to paint a pretty picture of their new roles. The reality is otherwise, “I loved my husband and thought life with him was going to be a breeze. I didn’t care if he was married earlier or that he had a 19-year-old daughter because I didn’t think it mattered. But it did. It mattered a great deal,” says Maheshwari candidly in her introduction to the book. The experience has left her wiser. “Now after nine years of travelling on this road, reading over a dozen stepmother guides, and venting with family and friends, I have finally figured out where and how I fit in.”

Not every stepmother can arrive at even an uneasy compromise with her new family. Indian society’s double standards paint the stepfather as a magnanimous man who has made the supreme sacrifice of taking on the responsibility of a wife and child who is not his own. There isn’t a whole genre of books, films and soaps portraying him in bad light.

But a stepmother has no such luxury. At best she is regarded as a gold digger with an agenda of her own.“Nobody understands that a woman has taken up the challenge of putting together a fractured family,” says Maheshwari.

The onus of making a stepmother’s role successful does not devolve on the woman alone. Her husband has a crucial part to play in a step family. If he has children he should finetune his ‘being in the middle’ relationship with them and his new wife. He must take a stand.

“Unfortunately, most remarried men with children are less husbands and more fathers in their new marriage...children sense that dad is feeling guilty so they do start to manipulate the situation to their advantage. Any chance of these kids having a respectful relationship with their stepmother is destroyed because she is the only one who can see through their game,” says Maheshwari in her concluding chapter.

Changing society’s perception of stepmothers will be a long, tortuous process, she says. But there are solutions. “In this world no stepmother is bad. So we have to review our fairy tales, sensitise society to the challenges stepmothers face which is very difficult. With increasing divorce rates in the next 10 years there will be 100 times more stepmothers. You can’t afford to keep this issue in the closet,” says Maheshwari.

Remarriage counselling could help promote harmony in a family. Once more remarriages succeed there is the possibility that stepmothers will be perceived better and receive more support for their efforts.

Arming a current stepmother or a woman who is thinking of becoming one with knowledge about what to expect and how to negotiate murky waters is the key to creating harmony in a step family. With greater peace all around, a stepmother is not left floundering trying to prove that she is not wicked after all.

Maheshwari’s book is an extremely useful one, full of advice and support for the stepmother. Crisply written, it is frank and dissects several awkward situations a stepmother is likely to face.

“After 10 years you will see happier stepmothers and realise that they are good actually. And slowly over centuries this myth will change. In the US things are already beginning to change. Many TV serials show stepmothers in a good light. That is not happening in our country. It will take time,” says Maheshwari.

“There are books on dogs and cats because we accept animals as part of our society. Stepmoms don’t even say they are stepmothers because they are afraid of society’s perception of them,” Maheshwari says.

More stepmothers need to step forth and say proudly that they are stepmothers. Society too must trash the mythology of the wicked stepmother.